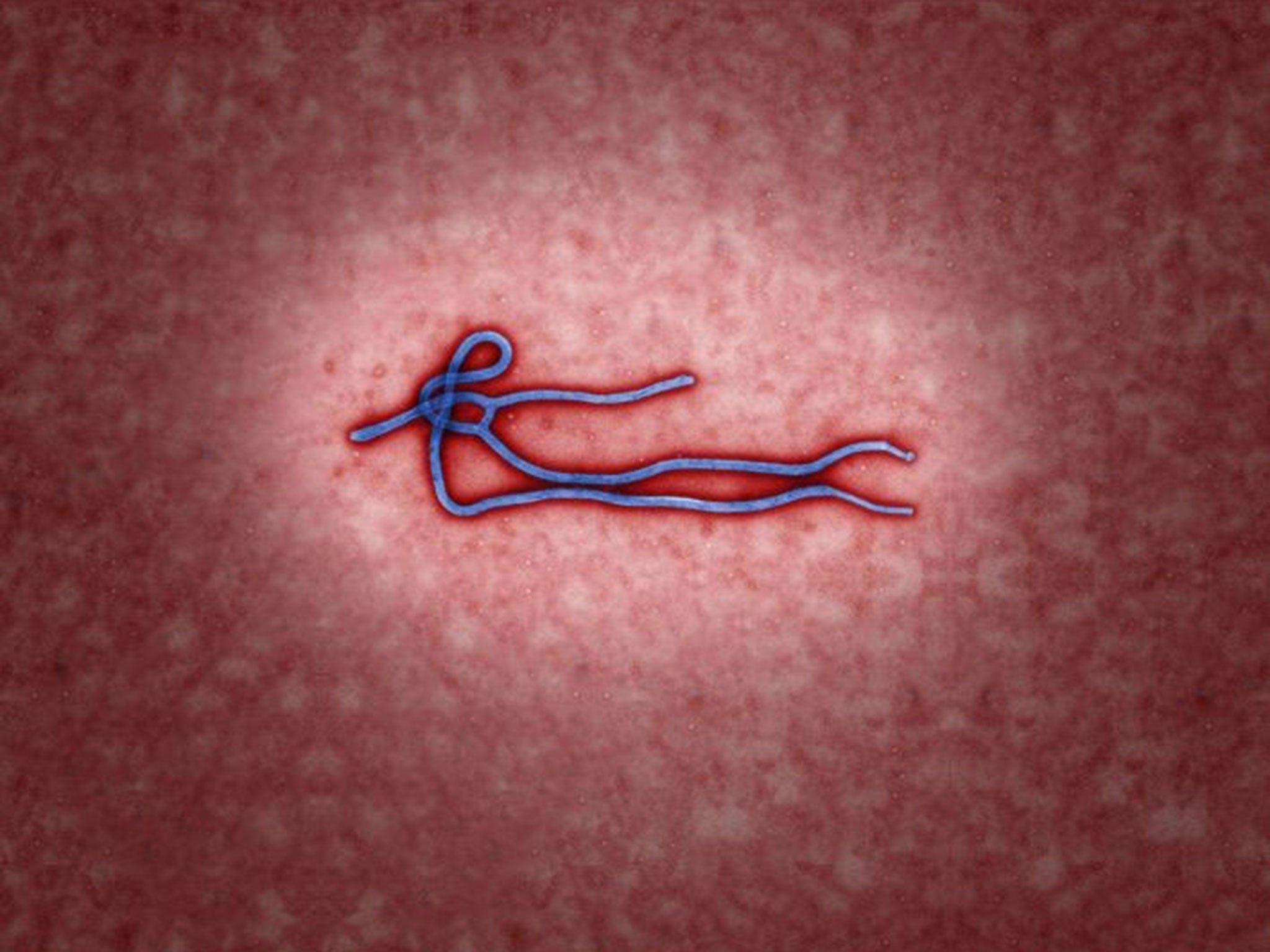

Ebola crisis: What are the symptoms – and how is the virus spread?

The UK's first case has been confirmed and another patient is being tested

A second patient is being tested for Ebola this morning after a health worker became the first person diagnosed with the disease in the UK on Monday.

A patient is being assessed for possible Ebola symptoms at the Royal Cornwall Hospital in Truro, Cornwall, and a woman who tested positive in Glasgow has been moved to London for treatment.

England's Chief Medical Officer, Dame Sally Davies said the risk to the general public remains "very low" but more cases could emerge over the coming months.

"The NHS is very well prepared for Ebola and the requirement for screening at selected ports of entry is being kept continually under review," she added.

What are the symptoms?

The NHS states that if someone is infected with Ebola they will develop a fever and experience headaches, joint and muscle pain, a sore throat and intense muscle weakness.

These symptoms are known to develop suddenly, between two and 21 days of a person becoming infected, but patients typically develop these symptoms after five to seven days.

After these symptoms develop people experience diarrhoea, vomiting, a rash, and stomach pain before liver and kidney functions deteriorate.

Ebola then causes internal bleeding and patients can bleed from their ears, eyes, nose or mouth.

How is Ebola spread?

Ebola is spread through contact with the blood and body fluids of an infected person, such as urine, vomit, diarrhoea and faeces, and saliva. The World Health Organisation makes it clear that patients do not become contagious until they are displaying symptoms of Ebola. They are not contagious during the incubation period.

The infection can be transmitted when these infected fluids come into direct contact with another person’s broken skin, or with mucus membranes, which are found in the lining of the nose and mouth.

The infection can also be spread through contaminated objects and surfaces, such as soiled clothing or bedding, by touching the contaminated areas and then touching broken skin, or the nose or mouth.

For men who survive the virus, sex with a condom is advised for a period of time as Ebola is present in semen for up to seven weeks after full recovery.

What should you do if you think you have it?

The NHS has treatment plans in place, but also highlights that there are other illnesses more common than Ebola that have similar symptoms such as fever, muscle aches, headaches, vomiting, diarrhoea, and could be linked to the flu, typhoid fever or malaria.

However, if a person is experiencing any of these symptoms within 21 days of returning from Guinea, Liberia or Sierra Leone, the NHS advises that people stay at home and contact the health service immediately on 111 or 999.

What are the protections the UK has in place?

Key airports and ports of entry, including Heathrow, Gatwick , Manchester and Eurostar terminals are running Ebola screens for passengers from at-risk countries.

People travelling to the UK from Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia are generally being tested before boarding a plane, and they are identified by UK Border Force officers when arriving in Britain. They are screened by nurses and consultants from Public Health England by having their temperatures recorded, their contact details taken and fill out a risk questionnaire.

If a person has had contact with Ebola patients but are not displaying any symptoms, they will be contacted by Public Health England daily to monitor their status.

Four hospitals have been placed on standby for any possible Ebola cases in the UK; the Royal Free Hospital in London, which cared for William Pooley, and hospitals in Sheffield, Liverpool and Newcastle, which have isolation beds for treatment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments