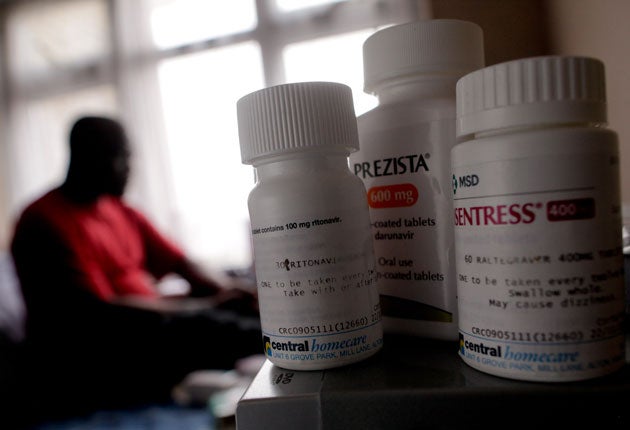

Immigration detainees 'denied life-saving drugs'

HIV-positive patients put at severe risk by UK Border Agency, doctors warn

Hundreds of HIV-positive immigrants are routinely denied essential medication in British detention centres, resulting in lives being put at risk, doctors say. They are demanding improved healthcare facilities in immigration detention centres or the release of those suffering from the condition.

Their evidence, in a report by the charity Medical Justice, will be heard in the Court of Appeal next month as three HIV-positive migrants seek to have their detention ruled unlawful because of the centres' failure to treat them properly.

The report, the first to examine the treatment of HIV-positive immigration detainees in Britain, scrutinised the care of 35 detainees with the condition, including women and children. It was produced using evidence from eight independent medical experts.

Some 60 per cent of detainees studied experienced disruption to their treatment as a result of being in detention, causing many to develop resistance to mainstream antiretroviral drugs, thus putting their lives at risk. In some cases, this made it impossible for them later to find effective medication.

More than three-quarters were deported with little or no medication to tide them over while they found healthcare in their home countries, despite government guidelines stating that they should be given a three-month supply before removal. Doctors say this presents a serious public health risk.

Some detainees were forced to undergo medical examinations while handcuffed to guards, despite being guilty of no crime. Others were denied access to hospital appointments with HIV specialists.

One pregnant detainee had less than a month's medication when an attempt was made to deport her. It is vital that treatment is not interrupted during pregnancy to avoid infecting the unborn child.

Around 60 per cent of all new HIV cases in the UK are sub-Saharan African immigrants, according to Unicef. There were 6,630 new cases of HIV infections in Britain in 2009 – more than double the number recorded a decade before. Most of those studied fled their country of origin to seek refuge in the UK, and more than 80 per cent discovered their HIV infection after arriving in Britain. Campaigners say this scotches the accusation that many asylum-seekers are in fact medical tourists.

The National Aids Trust said it deplored "the continuing failures in care" and called on the Government to do a full audit of HIV care in immigration detention.

Dr Indrajit Ghosh, a GP and HIV specialist, said: "The UK Border Agency claims that healthcare in its centres is equivalent to that in the NHS, but the report shows that being in detention leads to a situation in which these patients cannot access proper medical care. In the case of HIV, this is a threat to the patients' lives. HIV-positive people should therefore be released and properly cared for."

Diane Abbott, the shadow public health minister, warned the poor treatment resulted in a "serious public health hazard". "I've long been concerned at the medical facility for detainees. I think it's shameful they're given such poor treatment, but the situation with HIV is particularly worrying as it presents a very serious public health hazard," she said.

Alan Kittle, director of detention services at the UK Border Agency, said: "We take our duty of care extremely seriously. We provide primary healthcare facilities in all immigration removal centres which are equivalent to those available in the community... Referrals to the local primary care trust for additional healthcare services, such as treatment for HIV, are made in the same way as a GP surgery would in the community."

Case study

Pedro (not his real name), 43, from Angola is one of three HIV-positive former immigration detainees challenging his detention in the Court of Appeal.

"I found out I was HIV-positive three months before I was taken into detention. I knew my health wasn't good, and then I went to a check-up and found out why. I left Angola in 1993 to claim asylum. My case was refused four years later but nothing was done to take me out of the country. Then in August 2009 I was detained.

"I was supposed to be seeing an HIV specialist two weeks later but I wasn't taken to the appointment. It was a month before I saw a doctor. They put me on antiretroviral medication, which was a single drug taken once a day.

"During Christmas I was supposed to be seen again to get more medication, but they said they didn't have transport to take me.

"When I saw the doctor he explained that because I'd missed the drugs I'd developed immunity. Now the only pills I can take are very complicated, not available in Angola and expensive.

"I'm scared I'll get sent back. Here I know I won't die because I have the medicine, but back there I just don't know."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments