Taller people are more likely to develop cancer, study says

Scientists calculate that cancer risk increases on average by about 18% in women and 11% in men for every 10cm in height

The taller someone is the greater their risk of developing cancer according to a population-wide study into the complex relationship between height and the various forms of the disease.

Scientists have calculated that lifetime cancer risk increases on average by about 18 per cent in women and 11 per cent in men for every 10 centimetre (3.9ins) increase in height.

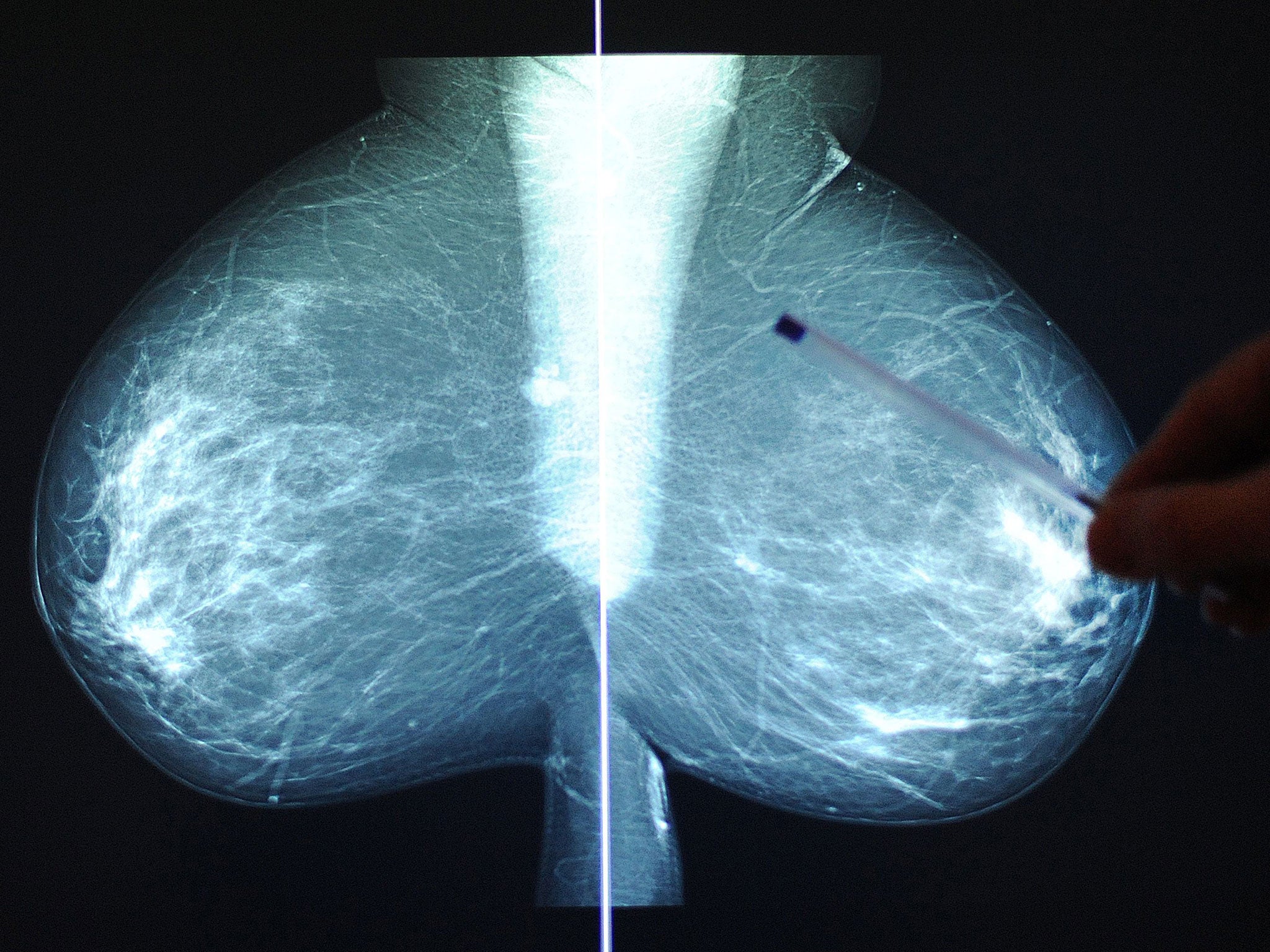

The risk is even greater for some individual cancers, with the risk of breast cancer in women increasing by 20 per cent for every 10cm increase in height, while malignant melanoma increases by about 30 per cent for every 10cm height increase for both men and women, the study found.

It is not the first time that researchers have identified a link between adult height and the risk of cancer, but it is probably the largest study to establish such a clear connection.

The scientists analysed the medical records kept on 5.5 million Swedish men and women born between 1938 and 1991, including height records from the country’s national passport register. The researchers followed the medical progress of each participant from the age of 20 until the end of 2011, which enabled them to establish the link between height and cancer.

The findings, which have not yet been published in a scientific journal but will be presented at a European endocrinology conference in Barcelona, were not influenced by socioeconomic differences such as education and income, said Emelie Benyi, a PhD student at the Karolinksa Institute in Stockholm.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest study performed on linkage between height and cancer including both women and men. It should be emphasised that our results reflect cancer incidence on a population level,” Ms Benyi said.

“As the cause of cancer is multifactorial, it is difficult to predict what impact our results have at the individual level… Identifying different risk factors for cancer could be the first step in understanding the mechanisms behind cancer,” she said.

Various explanations have been put forward to explain why taller people seem more at risk of cancer. These include greater exposure to growth hormone in childhood, greater number of cells in the body, a higher intake of calories, or, in the case of malignant melanoma, greater surface area of skin exposed to the sun.

“Our studies show that taller individuals are more likely to develop cancer but it is unclear so far if they also have a higher risk of dying from cancer or have an increased mortality overall,” Ms Benyi said.

“It is hard to predict what impact our results have on an individual level considering that cancer development is complex and depending on many different factors. We believe that there are much stronger risk factors for cancer than height, some of which are also preventable such as smoking and obesity,” she said.

Professor Mel Greaves of the Institute of Cancer Research in London said that for cancers such as breast and skin cancer other factors such as family history, reproductive patterns and obesity have a much greater impact in the risk of developing the diseases compared to height.

However, Professor Greaves said there is some evidence to suggest that exposure to growth hormone in childhood could be a significant factor in determining someone’s lifetime risk of cancer.

“People who have genetic dwarfism appear to have very little cancer… [they] have a mutation in their growth hormone receptor, and we know that growth hormone and growth hormone receptor are critical to tumour growth too,” Professor Greaves said.

“We know that, in humans, growth hormone not only stimulates bone growth during our growing years, but stimulates cell growth in general and blocks cell death. So the level of growth hormone someone has could affect cancer risk by pushing up cell numbers,” he said.

Jane Green, a clinical epidemiologist at Oxford University, said that adult height it not itself a “cause” of cancer, only a marker for factors relating to childhood growth.

“To put risk associated with a non-modifiable factor like height in context, it is worth noting that taller people have lower risks for heart disease, and a lower risk of death overall,” Dr Green said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks