Why is the norovirus such a huge problem for the NHS?

Traditional methods of self-care prove to be the best way to defeat the infuriating virus

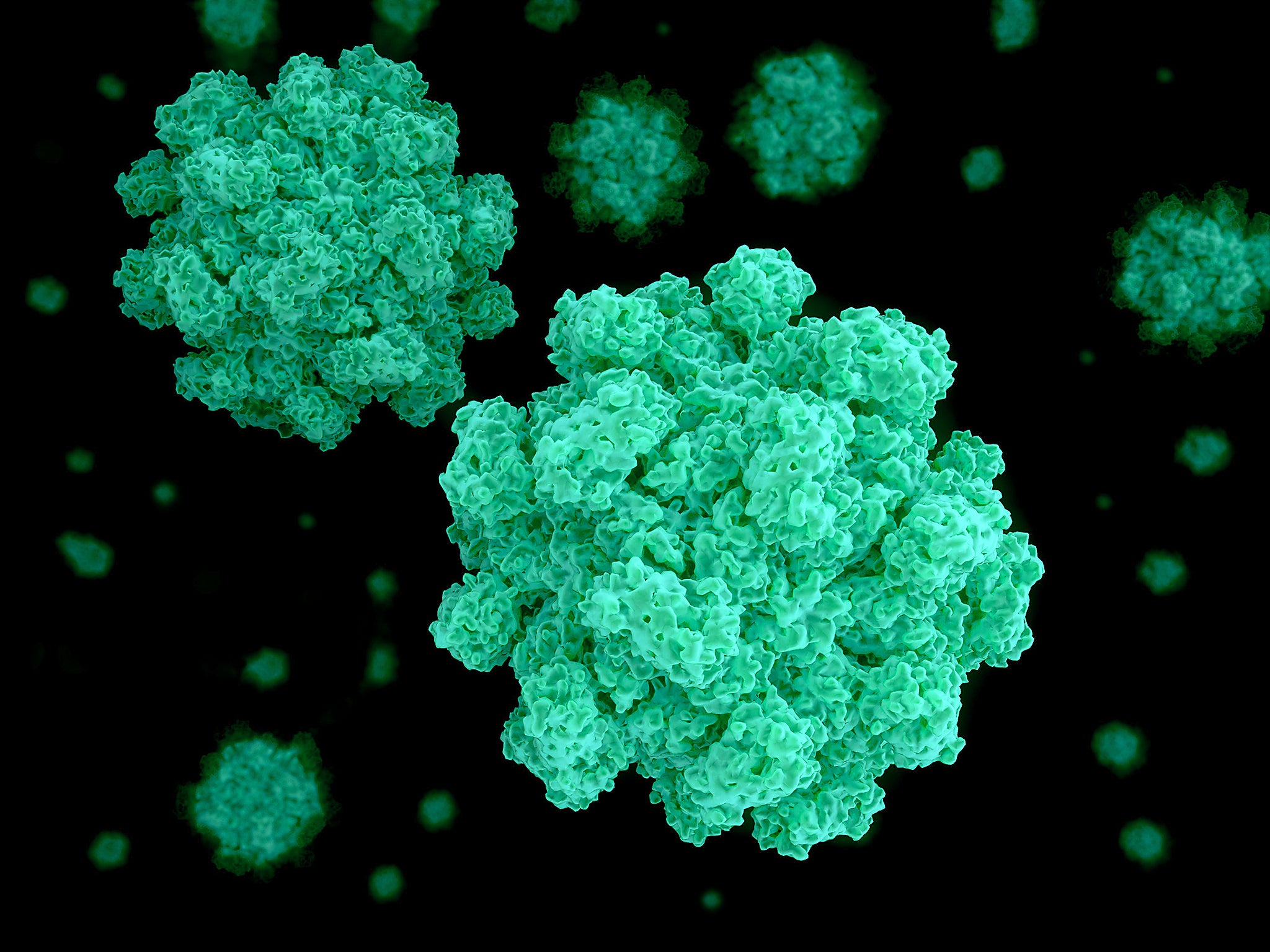

Norovirus, also known as the winter vomiting bug, is on the rise again, according to a report in the BMJ. A familiar set of warnings about ward closures and avoiding visits to patients in hospital was also issued, but why does this one virus cause the NHS such difficulty?

While norovirus does occur year-round, cases peak in winter and this clashes with the winter rush on the NHS. The symptoms of norovirus – diarrhoea and vomiting – typically last a day or two. While you may spend those days wishing you were dead, the chances of long-term harm from the infection are extremely low if you are otherwise healthy. Those most at risk from norovirus are the very young, the elderly and people with impaired immune systems (those said to be immunocompromised). Unfortunately, these are exactly the groups most likely to find themselves in hospital.

As a result of advances in transplant medicine and cancer treatment (which can suppress or affect the immune system), these immunocompromised patients make up an increasingly large portion of the population. While norovirus only lasts a few days at most in healthy people, those with suppressed immune systems can struggle to clear the infection; it can linger for weeks, months or even years. Fortunately, it is rare that full-blown norovirus symptoms are experienced for this long. But the virus does make it hard to absorb food and gain weight, which is a worry after major surgery and can make recovery much more difficult. As such, these patients are a particular concern.

Norovirus is very easy to pass ion. One tablespoon of diarrhoea from a single patient can contain enough virus to infect everyone in the world many times over. To make things worse, like many other viruses, people may remain infectious for several days after symptoms have resolved and not every infected person may be symptomatic. Many cases are traced back to food handlers who may appear well and have no idea they are infectious. The virus can be spread through touching infected surfaces or material and a lack of suitable handwashing or hygiene.

Outbreaks tend to occur in closed environments, such as hospitals, cruise ships, schools and retirement homes, as these all share common dining and social areas and have many people eating food prepared by others. In the case of hospitals, many have a food court or canteen which is shared by staff, patients and visitors. In summer, many escape outdoors on lunch breaks to enjoy the weather. But in winter, when norovirus peaks, everyone crowds together inside, away from the cold.

An expensive virus

Hospital staff are at an increased risk of catching norovirus themselves as they deal with large numbers of patients. This is not only unpleasant for the individuals concerned, but also means it’s possible for asymptomatic staff to spread the virus to patients and so exacerbate the problem. For this reason, hospitals are very careful about decontamination, staff training, and discouraging unwell staff from working for up to 48 hours after symptoms have resolved.

For an organisation which runs 24/7, and relies on a great deal of shift work, this can be very disruptive. All these disruptions come at a cost – lost hospital beds and closed wards, at a time when beds are already at a premium. In the two weeks before Christmas 2016, there were 15 hospital outbreaks of norovirus in the UK, 14 of which resulted in closed wards or restrictions on patient admissions. Past estimates of the costs of norovirus to the NHS put the total at over £100m (in 2002-03 prices). This is the same as employing over 3,000 extra specialist nurses, or around a third of the total cancer drugs budget.

The cost to the global economy of norovirus has been estimated at a whopping $44bn (£36.5bn), with $4.2bn of that to healthcare systems. At a time when NHS budgets are stretched, and hospitals are in debt, these additional costs are ones that hospitals can ill afford. For other seasonal and highly contagious diseases such as influenza, the NHS is able to offer and encourage its staff to take up free vaccinations in order to try and reduce the impact on staff, patient and visitor health. However, the absence of a vaccine means this is not yet an option for norovirus.

Vaccine trials are underway

Although no drugs or vaccines are available yet, several vaccine candidates are in clinical trials. Sadly, immunity to norovirus does not last for long, so, much like the flu vaccine, it is expected that regular vaccinations would be needed to make sure people remain immune. This would still be a huge benefit, and allow vaccination of workers at particular risk, or most likely to transmit the virus, such as NHS staff or those in the catering industry. The recent discovery of a means of growing different human norovirus strains in the lab, rather than having to rely on related animal viruses for research, will also boost efforts to find antivirals to help treat infection.

If you have norovirus, there is little your GP or hospital can do for you. The most a visit in person is likely to achieve is to spread the virus to other people. The NHS recommends that you stay at home, drink lots of water and, if you are concerned, phone your GP or NHS 111 for further advice.

Edward Emmott, research associate in virology, University of Cambridge. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks