Hirschsprung’s disease explained

A man in China had 12kg of compacted faeces and a large part of his gut removed by surgeons. The patient was suffering from a rare disorder known as Hirschsprung’s disease

Last week news broke of a 22-year-old man in China who had a large section of his colon removed. The man, Zhou Hai, had been constipated for a number of months. After seeking medical help for abdominal pain and difficulty breathing, he underwent extensive surgery and had a large part of his intestines, containing 12kg of faeces, removed. (For reference, the average human poo weighs about 100g.)

Hai was suffering from Hirschsprung’s disease, a rare congenital condition.

About 1 in 5,000 people are born with this condition. What is unusual in Hai’s case is receiving a diagnosis at the age of 22. Most people are diagnosed shortly after birth – although there have been a few instances where people have not been diagnosed until well into their adult life, as late as their 70s, in fact.

The earliest reference to a possible Hirschsprung’s disease (pronounced hirsh sproongz) case comes from Europe in 1691, when a Dutch anatomist Fredericus Ruysch described a young girl with abdominal pain and an enlarged colon. Following that, many other cases appeared in the medical literature concerning children with similar symptoms. But it wasn’t until 1888 that Harald Hirschsprung presented his work on two infants, who had died with enlarged colons, and gave the disease its name.

Hirschsprung’s work paved the way for others describing similar cases, but it took until the mid 1900s before the causes of the disease became more clear. A breakthrough in our understanding of Hirschsprung’s came in 1948 when two American doctors found an absence of nerve cells in the large bowel of children with the condition.

Today, we know that the disease sometimes occurs in families and might be caused by genetic mutations. But the causes of the disease are complicated, as more than one gene is thought to be involved.

Why nerves in the intestines are important

When consuming food, you control putting the food into your mouth, and you control when the food (in the form of faeces) exits the body. But you have no control over what happens in between. This depends largely on the action of muscles in the gut which are under involuntary control from the nervous system.

The intestines are a tubular structure with multiple layers, some of which are muscular. These muscle layers are connected to an automatic nervous system, which controls many of your organs. In the gut this takes the form of a network of nerves called the enteric nervous system (ENS). This system is responsible for moving the gut, helping it work to move food along the intestines, helping break food down and finally compacting it to form faeces when everything of use has been removed.

The connection between the nervous system and the gut is made very early in life, in the early stages of development in the womb. In Hirschsprung’s, the nerve cells fail to migrate to the gut during development, and the connection is impaired. The consequence is that the muscle layer which lines the intestines is no longer under full autonomic control, and the gut cannot move faeces along. So it accumulates, causing swelling of the bowel.

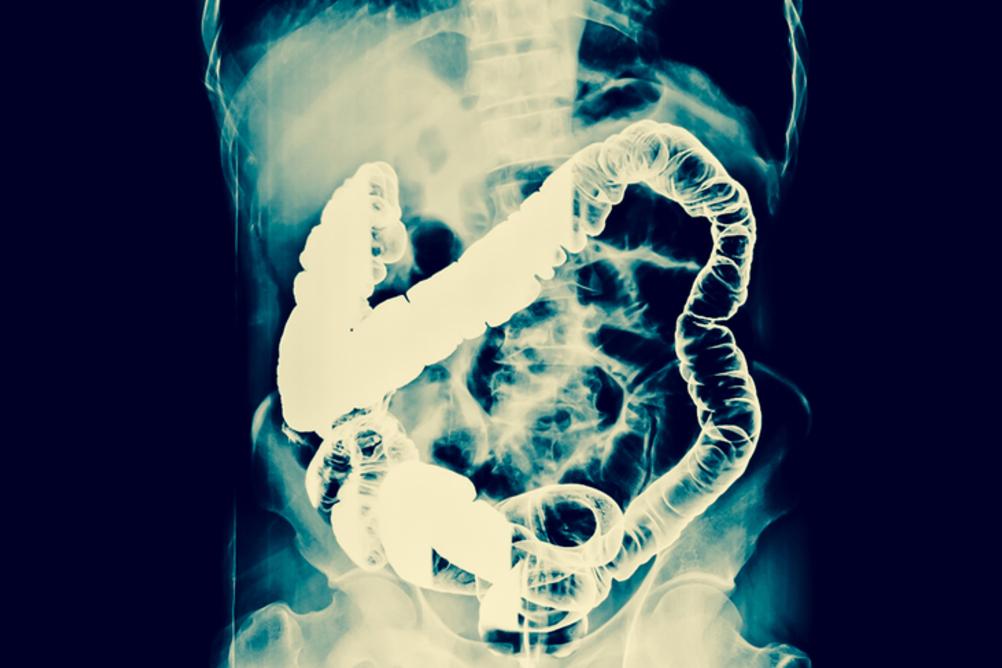

The first 48 hours following birth are critical for detecting the disease. Newborns usually have their first bowel movement within 48 hours. If the newborn baby doesn’t have a bowel movement during this period, it can be a sign of the disease. Doctors will usually perform some tests, such as x-rays and biopsy, to confirm a diagnosis.

Potential new treatments

At the moment, the only effective treatment for Hirschsprung’s disease is surgery. This involves removing the non-functioning part of the bowel (the bit with no nerves attached), and then connecting the remaining functioning part of the bowel to the anus. This procedure is called “pull-through” – it is the one that Hai had.

But there are new treatments on the horizon. The part of the nervous system which controls the gut (ENS), has its own subset of stem cells.

One possible solution is to use a patient’s own ENS stem cells to repopulate the section of bowel that is devoid of them. There are already some promising results in this field. A second promising therapy is to use genome editing CRISPR technology to correct mutations in genes that cause some variants of Hirschsprung’s.

This should help nerve cells to reach the gut during the crucial early stages of life in the womb. Although these treatments are still a long way off, they appear to be promising. With a bit of luck, in a couple of decades time, cases like Hai’s will be consigned to the history books.

Adam Taylor is the director of the Clinical Anatomy Learning Centre & a senior lecturer in anatomy at Lancaster University. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks