The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

50 years since homosexuality legalisation: Gay, queer and trans people reveal what the occasion means to them

Fifty years on from the Sexual Offences Act – and as Donald Trump bars transgender people from the US military – LGBTQIA people share what the anniversary of partial decriminalisation of homosexuality means to them, and how far there is left to go

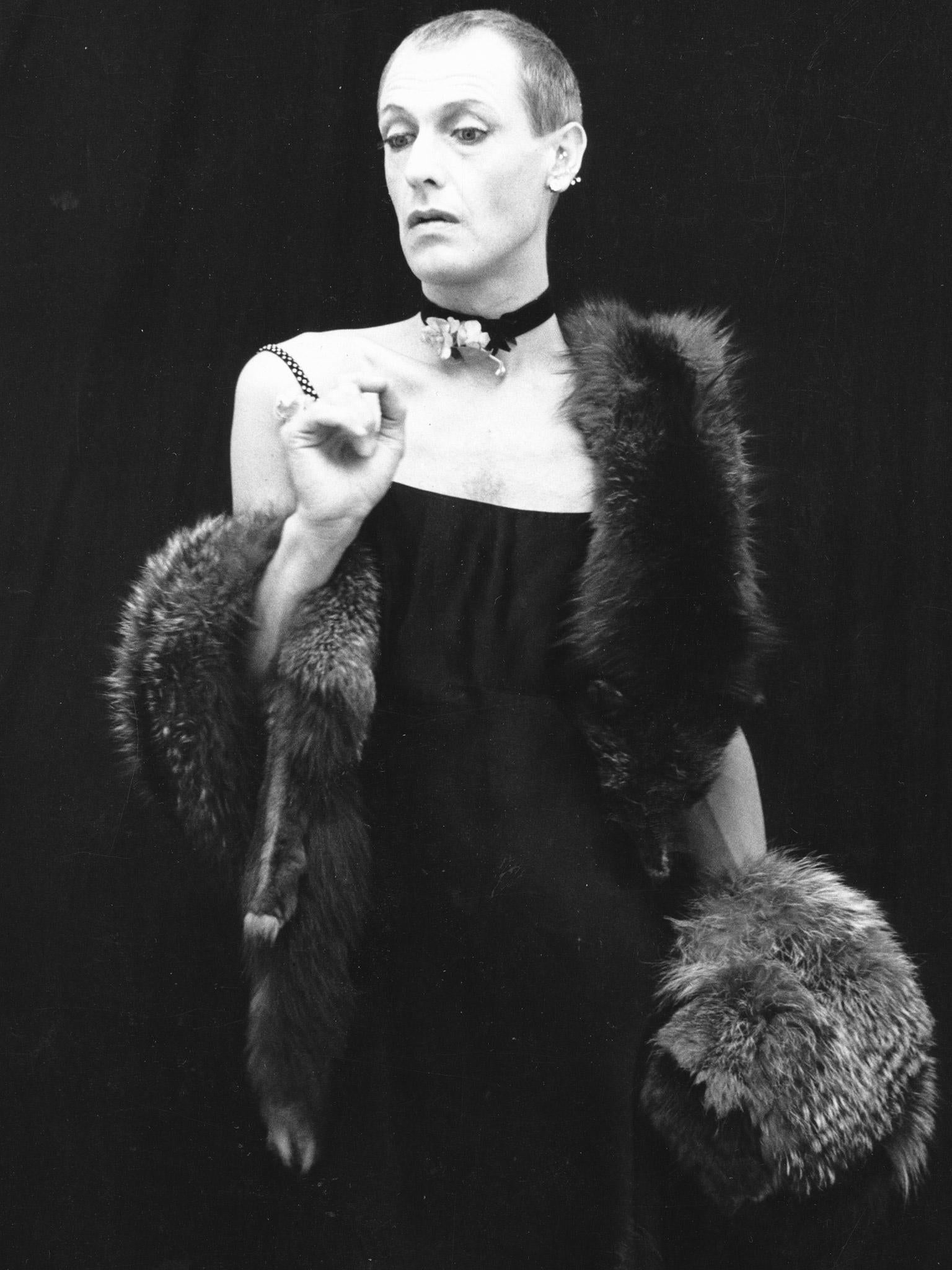

Attending one of the UK’s many LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual) pride events this summer – be that London’s July event, where stunning drag queens strutted on stage in Trafalgar Square, or Brighton’s rainbow-coloured parade set to attract hundreds of thousands of people to the seaside city in August – it might be hard to imagine that just five decades ago, it was illegal for men to have sex with men in this country.

On 27 July 1967, the Sexual Offences Act (SOA) was passed and sex in private between two men over the age of 21 was legalised in England and Wales. Gay men in Scotland and Northern Ireland had to wait until the early 1980s. And it wasn’t until 2001 that the age of consent for men who have sex with men was lowered to 16, and brought into line with heterosexual couples. In 2003, “buggery” was finally repealed from statutory law across the UK. Still, between 1885 and 2013, almost 100,000 men were arrested for same-sex acts.

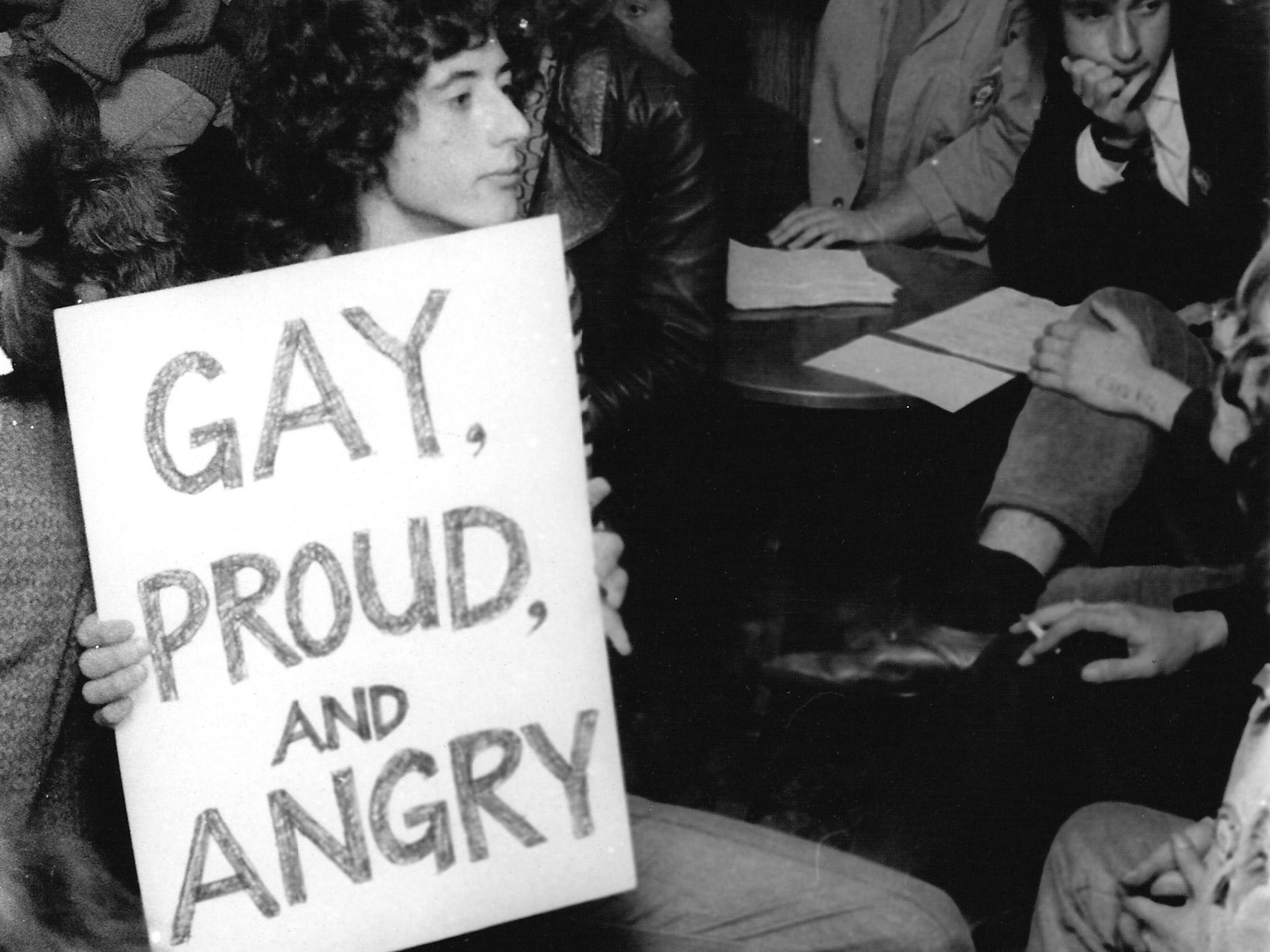

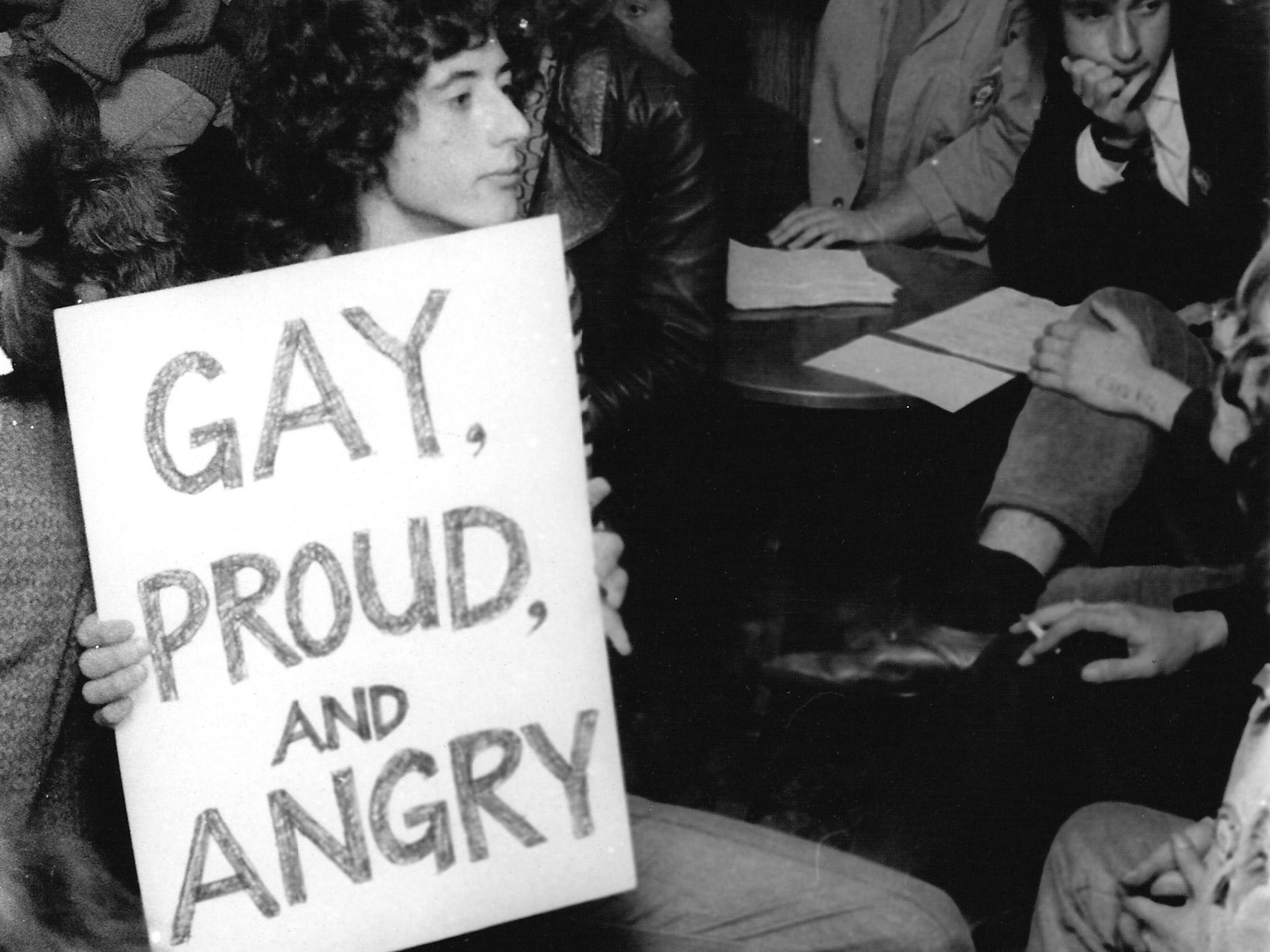

Behind this struggle were pioneering figures and groups, including members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), the Homosexual Law Reform Society and the Committee for Homosexual Equality. To mark 50 years since gay sex was partially legalised, we asked gay, queer and trans people to share what this anniversary means to them.

Stuart Feather, 77, is a painter, actor and author of Blowing the Lid: Gay Liberation, Sexual Revolution and Radical Queens. He was among the GLF activists who fought for the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality

Growing up in the Fifties in a culture of secrecy I began to develop a sense of injustice – and in the Sixties, a sense of defiance. I felt that to be gay was a badge of honour.

So when it came to that mean, insulting, partial, ageist, homophobic change in the law on 27 July 1967, it hardly touched me. As far as I can remember, all I did was go to the Boltons and Colherne in Earl’s Court for a drink.

More in the spirit of carry on camping, I carried on cruising in the only places society ever permitted us to meet each other: the secret pub, and the “cottage” (public toilet).

But nothing changed in the gay world between 1967 and 1970. In fact, there was a 300 per cent rise in the arrest of gay men for cottaging, as the police were livid that their 1865 Sexual Offences Bill had been ruined by liberal reformers and the politicians.

What really changed history was the advent of gay liberation in 1970, which demanded we come out and confront society and its building blocks – our parents – with the truth that we were not criminals or psychopaths, but citizens with the same rights as everyone else, and calling for all forms of discrimination to end immediately.

And although our sexual revolution was, in the end, only partial before it burned out, it irreversibly changed the face of this country for the better – not just for us, but for heterosexuals as well.

I remember in 1961 when Irish actor and dramatist Micheal Mac Liammoir brought his one man show The Importance of Being Oscar to the Apollo theatre, and the West End suddenly blossomed with young queens, myself included, all wearing in our buttonhole a green carnation. It was for me the flowering of a solidarity I’d never seen or experienced before.

It was a beautiful demonstration that change was in the air, politicised by The Homosexual Law Reform Society (founded in 1958), and its campaigning arm the Albany Trust, led by Antony Grey, and followed in 1966 by the Committee for Homosexual Equality.

We are all standing on the shoulders of earlier generations, and it is those activists – and the many who have gone before us – that I and 79 others will be celebrating at a lunch on the 50th anniversary this Thursday, in the very first year that has finally seen the last anti-gay legislation struck from the statute books.

The 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of the SOA has been an opportunity for me to return to activism, in order to show the world that it was, in the main, lesbians and gay men who struggled to make the changes we desired, and not the politicians at Westminster, or the trade unions. That is what I will be celebrating on Thursday 27 July.

I hope the young people of the LGBT community never get bullied, beaten up by their neighbours or police, or accused of being a paedophile, a psychopath or a criminal because they are lesbian, gay or trans. This anniversary is a celebration of all LGBTQ activism and acts of resistance over the last 150 years.

Peter Tatchell, 65, is human rights activist and the head of the Peter Tatchell Foundation

This anniversary makes me feel conflicted. 1967 was progress, but not equality. While it ended life imprisonment for gay sex, it was a partial decriminalisation. All the anti-gay laws remained on the statute book and convictions rocketed by 400 per cent in the years that followed.

I came out in 1969, aged 17, and began campaigning for LGBT rights. I knew the pioneers of gay law reform – unsung heroes of 1967, like Antony Grey, secretary of the Homosexual Law Reform Society in the 1960s.

In the 1960s, there were no LGBT role models. No public figures were out. The only time gay people ever appeared in the news was when they were exposed by the police or press for sex crimes or as spies, mass murderers or child sex abusers.

I had to figure out being gay and battling prejudice for myself. I looked to the black civil rights movement in the US for inspiration and for a model of how to do effective, successful protests.

Because of my LGBT and human rights activism, I’ve been assaulted 300 times. There have been 50 attacks on my flat, including three arson attempts and a bullet through the front door. I’ve been twice very badly beaten, leaving me with some permanent brain and eye damage.

Don’t accept the world as it is. Dream of a world without homophobia, biphobia and transphobia – and then help make it happen.

Shockingly, 45 per cent of LGBT pupils get bullied at school, and a third of all LGBT people have been queer-bashed at least once in their life. We need LGBT-issues to be made mandatory in sex and relationship lessons and PSHE classes in every school, in order to affirm and give confidence to LGBT pupils, and to combat the prejudice that fuels bullying and other hate crimes.

The huge progress towards equality in the last 50 years was not willingly conceded to us by MPs. They resisted equality for decades. We’ve only triumphed in the last two decades because of the dedication of tens of thousands of unsung LGBT people, and our straight friends and allies – some of who made great personal sacrifices to help us win LGBT freedom.

Don’t accept the world as it is. Dream of a world without homophobia, biphobia and transphobia – and then help make it happen.

Dani Singer is a 26-year-old tour guide and MA Applied Theatre student living in East London. They identify as trans non-binary

I’m grateful that, legislatively speaking, gay rights in particular, and broader LGBTI+ rights have moved forward in the past fifty years, beginning with this pivotal act in 1967. I am grateful that many of my friends and chosen-family can live openly in same sex relationships, particularly those of them in ‘normative’ relationships.

The thing is, the partial decriminalisation – like all legislation – doesn’t change people’s attitudes, and we’ve seen that clearly throughout modern history.

Arrests and harassment of gay men increased after the decriminalisation, and today, long after Section 28 and the right to marry, we see LGBTI+ hate crimes at an all time high. So I feel frustrated. I feel that there is a lot of government tokenism, pushing forward a lot of legislation which will allow and encourage LGBTI+ people to subscribe to heteronormative values (marriage, home ownership, employment rights, etc.)

These are all great, but they don’t come with the authentic desire to equalise rights for LGBTI+ people on our terms. Closure of services, spaces and removal of resources nationwide just shows the double agenda here.

People from the Gay Liberation Front or Lesbian Avengers, amongst other groups, have got us to where we are today, and really I’m just in awe of them. I’ve met most of them through campaigning groups I’m involved with, including ACT UP London and Sexual Avengers, amongst others, and now I call some of them friends, which humbles me constantly.

The thing that I find the most incredible about people who were there fifty years ago, and are still campaigning today, is their dedication and tenacity. They’re not resting on their laurels – many people would probably think: “Well, I’ve done what I set out to achieve, I can get on with life now.” But they’re still fighting and fighting after fifty years – something which is both inspirational and deeply saddening. Older people in their seventies and eighties shouldn’t have to be fighting a fifty plus-year battle, or begging the government for an apology before they die. They should be celebrated as pioneers and heroes, not just of the LGBTI+ community, but of human rights across the board.

Being able to walk down the road without being attacked isn’t a privilege, it’s a basic human right

I attended a Jewish secondary school which expelled pupils who were openly LGBTI+, and I was hugely suppressed during a pivotal time in my development, when I should have been exploring my sexuality and gender identity as well as my wider identity. I’m fortunate now that the progressive synagogue community I’m a part of is really inclusive – last week the Rabbi, who is a woman, even gave a sermon about gender equality and trans rights.

We forget that there are still 42 countries in the commonwealth, and over seventy countries worldwide, which criminalise homosexuality – with most of those as a result of Britain’s own homophobic laws enforced during the empire. There is more to this struggle than being able to walk down the road after dark without being attacked. That’s not a privilege, that is the basic human right we all want, and which many in our community still don’t have.

Yusuf Tamanna is a 27-year-old freelance multimedia journalist. He is 27 and identifies as a gay man

This anniversary makes me think of all the gay men and women who didn’t live long enough to see how far we have come today. There is still so much work to do. It’s still illegal to be gay in some parts of the world, and my heart really bleeds for all those unable to be themselves.

We take for granted how many rights we have here as gay men and women living in the UK, and it’s always important – I think, anyway – to remember not everyone else is afforded this.

If I could speak to the activists who fought for the cause 50 years ago, I’d say thank you. It seems like such a blasé thing to say to people and groups who pretty much fought for me to be able to be me. But honestly, I don’t think I could ever put into words how grateful I am for all you went through for the rest of us.

The gay community has an issue with segregation and divisions across race and class. Whether you’re masc or femme, I wish we could all get our heads out of our asses and look around and realise that we are all we have. The gays were the ones fighting for gay rights; we have to protect each other.

I plan on marking the occasion by being as unapologetically gay as possible

I’d also like to pay tribute to my mum, who always tells me I should be as gay as I want and not to shy away hiding myself. Also, drag queens: I credit them for educating me on what gay culture was and is all about.

Before I came out, I had this warped idea that being gay was a death sentence and I’ll remain miserable for the rest of my life. But drag queens showed me that you know what? Being gay is pretty incredible and we have such rich culture.

I think the concept of ‘coming out’ is a really horrible thing. The pressure, the “what if?” It’s such an isolating experience. I hope the younger LGBT people don’t have to fear coming out to their friends and family. I hope society becomes more comfortable with gay people, so that we don’t have to come out and we can just be us, you know?

People should remember that 50 years wasn’t a long time ago. To think it was criminal for men to have sex with one another not so long ago should be a sobering thought to any gay man or woman who thinks all this activism stuff is unnecessary in 2017.

For straight people too: just because we can get married, it doesn’t mean we’re equal. It doesn’t even mean we’re accepted. I plan on marking the occasion by being as unapologetically gay as possible

Stewart Who is a 47-year-old DJ, writer and former editor of QX magazine. He identifies as a queer man

A Miriam Stoppard book my parents bought for me (explaining sex to teens) was the first time I saw in print that it was okay to have same sex experiences. My granny was a fan of Boy George and somehow, that helped me. Jimmy Somerville and Marc Almond both made brilliant music and were unapologetically queer in the Eighties when I was a teen – they alarmed me while I was closeted, but ultimately strengthened my esteem and political direction.

What do I hope that young LGBT never have the experience?

Growing up as a teenager in the midst of the AIDS crisis I endured tabloid hysteria, playground horror, fear of the future and equating sex with death and judgement for the best part of two decades.

With no internet or smartphones, finding oneself young and vulnerable in cruising areas where you could be assaulted, arrested or caught without an umbrella. Being under the age of consent and therefore a legal risk to your lover.

Having to attend the funerals of friends, lovers and acquaintances who died before life-saving HIV drugs. Seeing almost no positive role models in pop culture, and feeling shame at seeing gays on TV like John Inman who appeared in Are You Being Served.

I hope they never experience the grief and loss of six dead boyfriends in a lifetime. Or hearing homophobic abuse at home, unchallenged by family. And having utter distrust of the police.

Growing up as a teenager in the midst of the AIDS crisis I endured tabloid hysteria, playground horror, fear of the future and equating sex with death and judgement for the best part of two decades.

Now, we need to continue fighting for queer refugees, battling racism on the LGBTQI scene and in wider society, trans rights, the continued funding of sexual health initiatives and support for mental health issues, compulsory sex and relationship education – regardless of faith or resistance from parents.

I feel horribly sad and angry for LGBTQ people who suffered at the hands of the law prior to decriminalisation, and grateful for all those who fought to make our lives a tad more secure. One the one hand, I feel hopeful for the future and that we’re on better footing legally.

But on the other hand, look at the progress in legislation supporting the equality of women. Many feel that hard won legal rights are no match for a fighty, white patriarchal society that finds other ways to oppress the marginalised. And look – Trump happened; that doesn’t bode well for people of colour, women or queers. The fight ain’t over yet.

Ata Rahman is a 28-year old digital communications officer based in London. He identifies as a gay man

The anniversary makes me proud to think how far the UK has come along, but it also makes me realise that I don’t know enough regarding the struggles that LGBT people before me had faced. I also recognise that there is still work to be done, and while this is an important milestone and celebration, it is not the end of the fight.

My parents are Muslims and though they do not accept me, we have managed to maintain a somewhat positive relationship. I hope young people in the future don’t have to go through what I’ve been through.

I hope they find it easier to come out to their families, and that families have a better understanding of how to help their children through this. I hope that parents who have religious or other beliefs that make them think being an LGBT person is wrong come to realise that, even though they may not fully understand their child, that their religion preaches love and acceptance and they should practise this.

My friends have always been consistently supportive, and though they’ve not specifically dealt with homophobia that I’ve experienced, their support is enough to know that I am accepted and loved for who I am.

We need to continue fighting for equality within minority communities – the presence of LGBT people of colour is still too small, and their views and experiences need to be taken more into account. We need to improve attitudes to them within the community as well as from outside, spanning from treatment at entry points to LGBT venues, to the sexual fetishising them by individuals and groups, to a wide range of concerns they report.

The other largest challenge in my view is that of mental health. Depression and anxiety are rife within the LGBT community, and this needs to be tackled through more specialist groups, such as an improved understanding on the part of employers.

The struggles and hardship faced by those involved to achieve what we have so far are significant, but though some battles have been won, the war against social acceptance is far from over.

Dan Glass, 33, is a performer, human rights activist and the tour guide and founder of “Queer tours of London – A Mince Through Time”

The 50th anniversary means everything to me. Without creative and sexual expression on your own terms, you’re more like a stone than a human. It makes me feel alive, full of hope and nourished with the conviction to carry on the struggle for full LGBTQIA+ equality.

If I could speak to some of the activists who fought for decriminalisation 50 years ago, I would let them know how transformative their acts of love have been, and continue to be. Often it’s the daily subtle acts of support, love and empowerment that people say, rather than the big grandstand gestures, which make the difference.

It’s an act of providing belonging, affirmation, identity and the ability to genuinely love others and yourself in this world. Life’s so short it’s important you let people know when they are great as well as when they are shit.

Often it’s the daily subtle acts of support, love and empowerment that people say, rather than the big grandstand gestures, which make the difference.

Now, we need to raise awareness of rape and sexual violence within the LGBTQIA+ community. Because we have been invisibilised for so long, and continue to live without adequate infrastructure for our community to understand how to exist in the world, cycles of violence continue. If we don’t have space to challenge our oppression, we can easily step into the shoes of the oppressor.

An incredible amount of progress has been made in the relatively short amount of time of 50 years. However, this “progress” is like two ships in the ocean sailing in opposite directions.

You have the SOS SOA (Sexual Offences Act) boat sailing into the sunset carrying the section of our LGBTQIA+ community that it was set up to benefit – predominantly white, gay, cis-gendered middle-class men. On the other boat you have the rest of the LGBTQIA+ community, who without recognition continue to be invisibilised and struggle to get a lifering thrown from SOS SOA.

The practical reality is the rise in LGBTQIA+ homelessness, not a single permanent bar for lesbians in the whole of London, no fully accessible LGBTQIA+ spaces – the list goes on. None of us are free until we all are free.

LGBTQIA people should keep climbing the mountain – it’s worth it! Keep mincing, keep cottaging, keep resisting, keep loving, keep fighting – your everyday acts to exist, survive, love and thrive have given birth to a new world of freedom.

Matt Horwood, 28, is the senior communications Officer for Stonewall. He identifies as a gay man

It’s important to remember that we stand on the shoulders of giants: campaigners who worked tirelessly so we could live the lives we do today, in times of extreme opposition. However, the anniversary should serve as a reminder of what’s left to do, and our own responsibilities in achieving that.

Trans people still face numerous legal hurdles that prevent them from being able to live as their authentic selves. Anti-LGBT hate crime is still a huge issue in Britain, as is anti-LGBT bullying at schools, and different parts of the community still face specific and often dual discrimination – for example, LGBT people of colour.

People underestimate the power that sharing their stories has, and it’s really important that we celebrate the role models who are brave enough to do so. Visibility of diverse role models is so vital for lesbian, gay, bi and trans people, especially those who feel less able to be themselves or less represented.

It’s also important for all people in general to understand the wonderful diversity of lesbian, gay, bi and trans people in our community – this is not something we often see in pale, male and stale LGBT representation in the media.

I hope young LGBT people never have to fear being themselves

So I’d shout out and celebrate the people who are proactively sharing their stories, and making sure that every single lesbian, gay, bi and trans people sees people like them.

What experience do I hope LGBT young people won’t be subjected to? The fear of being myself, whether that means holding my partner’s hand while walking down the street, using male pronouns to talk about my partner when meeting new people, and feeling able to fully participate in spaces that aren’t specifically LGBT-inclusive.

I may be marrying my partner next month, which is fantastic, but that doesn’t mean that I’ve not faced discrimination and abuse from people when publicly talking about that in certain aspects of my daily life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments