Inbreeding is coming: Everything Game of Thrones has taught us about incest

The celebrated series and its new spin-off ‘House of the Dragon’ are underpinned by all kinds of mucky brother-sister rutting and grim familial relations. In response, Tom Ough has bravely fact-checked many of its ickier scenarios, asking the incestuous questions you were far too frightened to ask

As we’ve been reminded by the new Game of Thrones spin-off, Westeros and incest go together like brother and sister. That being the case, it probably doesn’t qualify as a spoiler to reveal that inbreeding rears its misshapen head in the second episode of House of the Dragon. But if you haven’t seen the episode – and would like to save the incestuous plot turn for when you get round to watching – do not read on.

First, a quick reminder of the incest we’ve previously encountered in Westeros. The original Game of Thrones began with Bran Stark peeping at the incestuous canoodling of Jaime and Cersei Lannister, twins who were themselves the product of Tywin Lannister’s marriage to Joanna Lannister, his cousin. Tywin and Joanna’s marriage, by the way, doesn’t count as incest in the eyes of Westeros, just as marriage between cousins has, in the real world, generally been acceptable. We shall focus today on even closer inter-relation relations.

Cersei’s three children, putatively fathered by her husband, King Robert, were in fact sired by Jaime. Their eldest, Joffrey, was a sadistic wrong’un, much like several members of the Targaryen family that Robert and Jaime had deposed. Jaimie killed “the Mad King”, Aerys Targaryen, whose insanity – he became obsessed, we are told, with burning people alive – is attributed within the show to centuries of Targaryen inbreeding. “Every time a new Targaryen is born,” King Jaehaerys says, “the gods toss the coin in the air and the world holds its breath to see how it will land.”

As far as the Targaryens are concerned, the upsides of inbreeding are obvious. Not only can the family bulk-buy the same peroxide-friendly shampoo, they also keep their power concentrated rather than dispersed. It happens over and over again, deliberately and accidentally. Jaeherys’ descendant Daenerys Targaryen, viewers of Game of Thrones will recall, escapes a troubling relationship with her brother, Viserys, and eventually ends up shagging Jon Snow, bastard son of a nobleman from the other end of Westeros. Somehow, in Jon, Daenerys has unwittingly found her long-lost nephew. It is as ancient and well-maintained a family tradition as riding dragons.

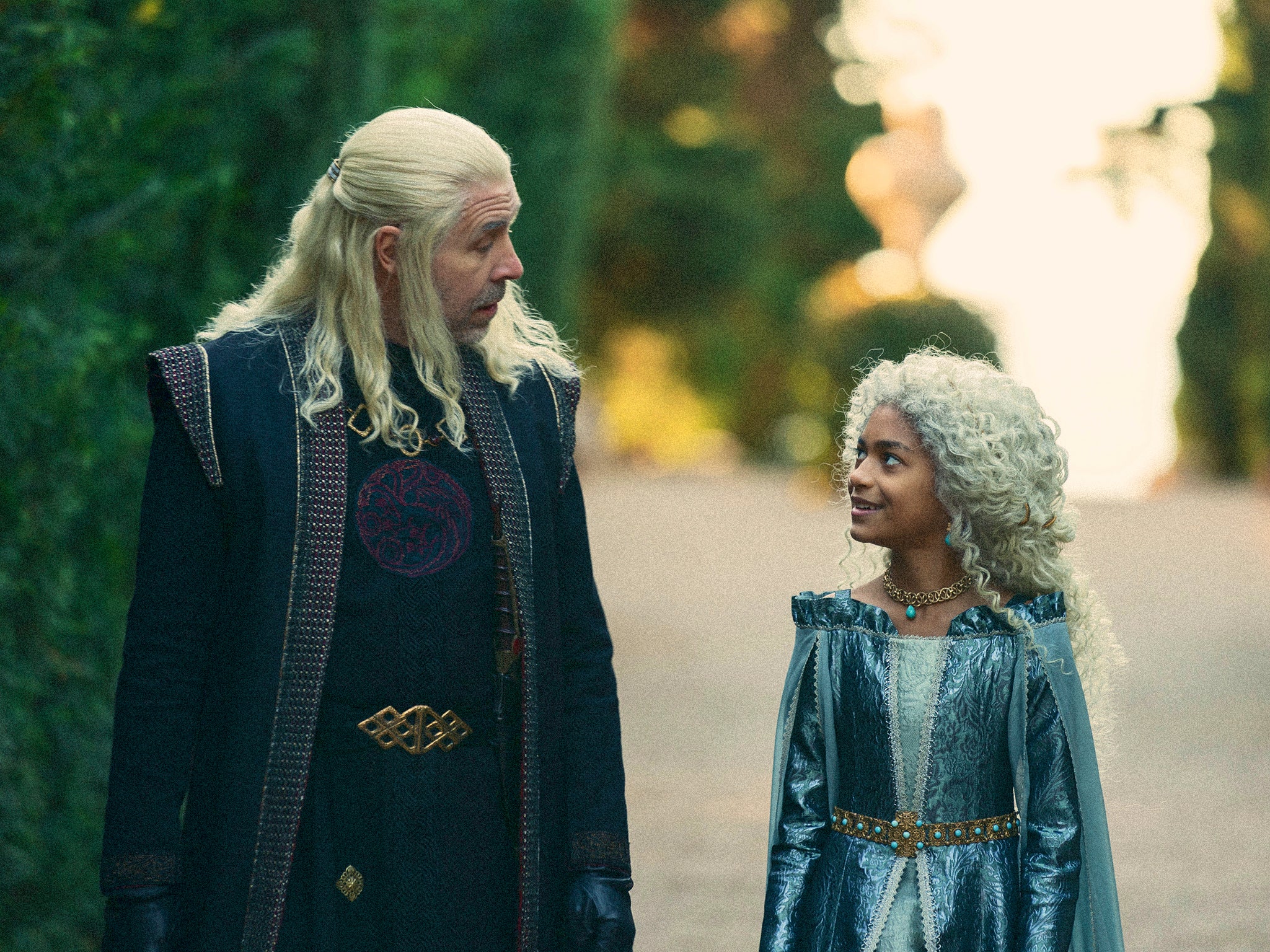

It is a tradition that reappeared in last night’s episode of House of the Dragon. King Viserys (an ancestor of the aforementioned Viserys) is offered the hand of Lady Laena Velaryon shortly after the death of his first wife. Laena is not only 12, but Viserys’ first cousin once removed. (What this term means here is that Viserys’ grandparents are Laena’s great-grandparents; Laena’s mother is Viserys’ cousin. Viserys and Laena are cousins at one generational remove.)

Viserys thinks better of marrying the 12-year-old (so far, so woke), choosing instead Alicent Hightower, the apparently teenage best friend of his 15-year-old daughter (ho hum). Alicent, one presumes, is not-so-distantly related to Viserys, but, for once, a Targaryen takes the least incestuous of two options.

Overall, though, the family Targaryen knows to keep it in the family – even more so than real-world royal families. As the geneticist Razib Khan points out, “Daenerys Targaryen’s inbreeding coefficient is 0.375. Charles II, the last Spanish Habsburg, who was impotent ... mentally disabled and could barely walk, had a coefficient of 0.254.”

What is an inbreeding coefficient? Does marrying your cousin qualify as incest? And what, fundamentally, is the problem with incest? David Balding, honorary professor of genetics, evolution and environment at University College London, is on hand to explain.

First of all: what qualifies as incest? Is Viserys in the clear? Scratch that – is either of the potentially incestuous Viseryses in the clear? “There’s no real biological rule,” says Balding. “In most societies that I’m aware of, the borderline is either side of cousin, so some societies allow cousin marriages” – this category includes Britain – “and others don’t. But I think ‘incest’ is probably normally reserved for first-degree relatives: brother, sister, father, daughter, that kind of thing.”

And why is it taboo? “You’ve got a whole lot of defects in your DNA,” explains Balding. “Most of it doesn’t matter too much, because you’ve got two genomes, one from your mother and one from your father. And in most cases, as long as one of them is good, you’re fine.”

But if your parents are related, that greatly increases your chance of getting two copies of the same gene. In this way, children of incest are more at risk of what are known as recessive diseases such as cystic fibrosis and sickle-cell anaemia, which require two copies of the same gene. “The risk of those diseases in the general population is pretty low. So doubling the risk” – which one might do by procreating with one’s cousin – “is thought acceptable by some societies and not by others. But then if you get much closer, like uncle-niece and brother-sister, then the rates go much higher.”

This is bad news for the Lannister twins and the pairing of Jon and Daenerys. Essentially, a high level of genetic diversity between parents is supportive of the good health of their children. Balding describes how the body can compensate for one poor-quality bit of DNA, but not a pair; how inbreeding in plants and animals is associated with infertility.

Of Charles II, the maligned Habsburg king, Balding says his inbreeding could “definitely be a contributing factor” to his various disabilities. Portraits of the king, who did not sire an heir and as such was the last of his line, show a jutting “Habsburg jaw”. He may have had combined pituitary hormone deficiency and distal renal tubular acidosis. His family tree would make just as much sense upside down as the right way up. His autopsy, according to the physician who administered it, revealed (somewhat improbably) a corpse that “did not contain a single drop of blood; his heart was the size of a peppercorn; his lungs corroded; his intestines rotten and gangrenous; he had a single testicle, black as coal, and his head was full of water.” Let that be a lesson to those who rooted for Jon and Daenerys to get together.

For a king marrying his cousin, Balding says, “the odds are the offspring will be okay. But he will have a much higher risk than if he’d married a commoner”. One doubts that many viewers are rooting for Viserys to marry a 12-year-old; this is yet another reason to hope we never see it happen. “They’re relatively distant,” says Balding of Viserys and Laena. “I think they’d still get some effects there, but not huge ones. Then again, he says, sometimes royal families are related by different lines of descent. (This is certainly true of European royalty; Prince Philip and the Queen, not atypically for their demographic, were third cousins.) “So the risk could be higher again.”

And what of the Targaryens as a family? Surely the destructive madness is less an exemplification of the perils of intermarriage than it is an authorial invention. “It’s probably a bit of both,” says Balding. “I think it definitely makes sense. There are some mental deficiency kind of outcomes associated with inbreeding, so that’s certainly generally plausible, but of course, people are likely to exaggerate all of that.” (More complex conditions such as schizophrenia, he says, do not come down to having two copies of the wrong gene; there is no easy answer to Targaryen madness and violence.)

Unlikely as it might seem from a viewing of Game of Thrones, humans are generally strongly disinclined – more so than other mammals – to have sex with their immediate family members. “It’s interesting how that evolved,” says Balding. “It’s not really well understood how that resistance happens, but it definitely does happen.”

As for the coefficient, a brother-sister pair will have an inbreeding coefficient of 0.5, or 50 per cent. Even in dogs, says Balding, “anything bigger than 10 per cent is considered kind of bad news.” Then again, no human is entirely unrelated to another. “Eventually, if you go back far enough,” Balding tells me, “you and I will have ancestors in common.”

Perhaps House of the Dragon has yet more inbreeding to offer us. Viewers have wondered whether there were “odd, incest-like vibes” between Prince Daemon, who is Viserys’ brother, and Princess Rhaenyra, Viserys’ daughter, when he puts a necklace on her in the first episode. The plot of the rest of the show’s first season remains an expertly guarded secret, but given where this all ends up – mad Daenerys Targaryen torching King’s Landing – we can assume that the family continues to keep its procreation firmly in-house.

‘House of the Dragon’ airs weekly on Sundays in the US, with the UK premiere arriving 2am the following morning on Sky. The episode will then be repeated at 9pm on Mondays, and will be available to stream on Sky and NOW after its initial airing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks