‘How could I have been so stupid?’: People are still being catfished – and it still isn’t a crime

Despite few people talking about it anymore, catfishing remains prevalent in online dating, leaving trails of emotional wreckage in its wake. Saman Javed speaks to experts and victims about what we can do about it

Erika had fallen for Connor. He’d followed her on Instagram, and the pair began chatting. There were likes loaded with subtext. The odd story reply. Then long, flirtatious conversations and an exchange of numbers. They’d text every morning and phone one another at night, Connor sharing deeply personal parts of his life. Erica reciprocated. Then doubts set in.

Connor followed fewer than 50 people, but had more than 500 followers himself, many of whom seemed to only post stock images and spam. Erika asked Connor if he was being genuine with her, and he insisted he was. Erika took his word. But her suspicions were raised further when he kept cancelling planned in-person meetings. “He called me and said he was on his way, but kept delaying it, delaying it, delaying it,” Erika recalls. “He’d say ‘obviously I’m going to meet you; I really want to see you’. We’d make another plan, and then he’d bail again. It was like a game of cat and mouse.”

Connor refused to video chat, other than showing his face for “around two seconds” during a call on Microsoft Teams. Whenever Erika asked for proof of his identity, he’d go cold and stop responding. By this time she was also emotionally invested in him, regardless of his evasiveness. “I ended up not saying anything at all because I didn’t want to lose our connection,” she admits. “I was in denial, because honestly, I didn’t want to believe he wasn’t real.”

Then Erika found out the truth. Having Reverse Image searched more than 30 of Connor’s photographs, she discovered one was taken not by the person she’d been speaking to, but by a successful entrepreneur in the US. “I immediately felt sick,” she says. “I felt violated. For the first time in my life, I didn’t feel mentally strong enough to handle the situation in front of me.” Plunged into deep grief and not feeling mentally strong enough to confront “Connor”, Erika blocked him on every social media platform and hasn’t spoken to him since. When she opened up about the incident to family and friends, she received little support. “They would say the signs were obvious, and that I shared too much. They’d tell me I was naive, and I’d come away feeling even worse. But people meet and speak to people on the internet all the time, how would I have known this would [happen]? All I kept thinking was: how could I have been so stupid?”

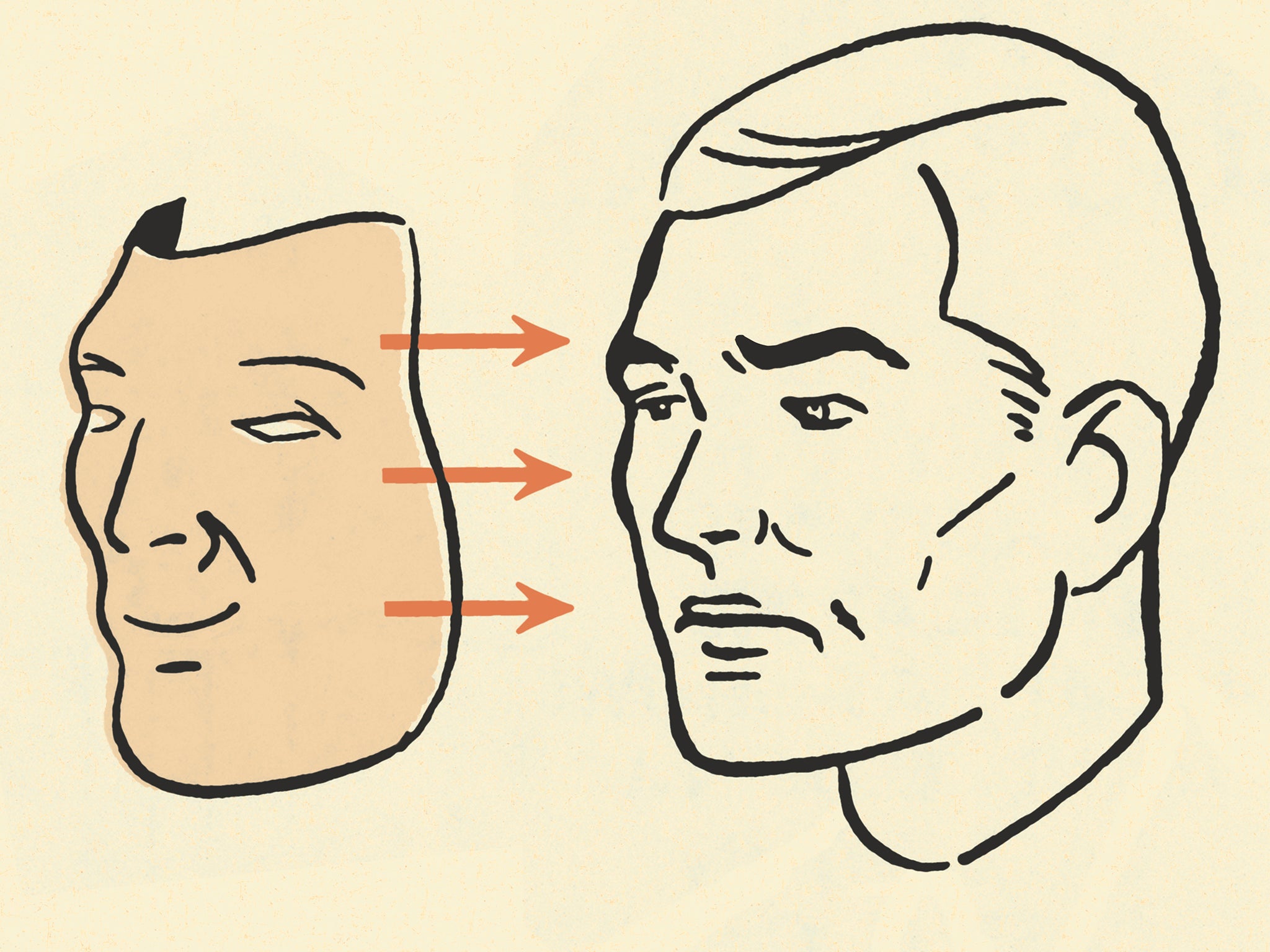

Erika had been catfished – a term coined by the 2010 film of the same name, in which photographer Nev Schulman discovered his online girlfriend, Megan, was actually a fake persona created by an artist named Angela. The phrase was officially recognised by the Oxford Dictionary in 2014, and describes a person who pretends to be somebody else on social media in order to attract others. As catfishing is not a criminal offence, there are few statistics on its prevalence. In some instances, a catfish may elicit money from their victim – a criminal activity also known as a romance scam. As per the FBI, 24,000 people were victims of romance scams in the US in 2021. In the UK, 8,863 cases of romance fraud were reported to the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau between November 2020 and October 2021.

In a catfish romance, there’s a tendency for the victim to blame themselves for not spotting the signs. This is amplified by a general response from the public to blame victims for falling prey to catfishing. “It’s not because we aren’t caring or empathetic, but because the victim resembles us in some way, and we don’t want these things to happen to us,” says Christopher Hand, a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Glasgow. “Generally, we are raised to believe good things happen to good people, so when we see a bad thing happen to a generally ‘good’ person, we try to find fault with the victim.”

People would be wrong to think it can’t happen to them, because it can absolutely happen to anyone

Hand believes there needs to be more widespread education among the public, so that they may offer non-judgmental support to those who do fall victim to the practice. “Meeting people online is now a part of our lives; it’s going to be reality for most people,” he continues. “Catfishers are sophisticated and they know what they’re doing, especially when they use real people in their identity. People would be wrong to think it can’t happen to them, because it can absolutely happen to anyone.”

Research around why people catfish and how they choose their victims is limited. One study carried out by the University of Queensland, Australia surveyed 27 self-confessed catfish from around the world. The study found that 41 per cent took part in the practice because they were lonely and wanted someone to talk to. Around one-third reported hiding behind a fake profile because they felt dissatisfied with their own appearance, while two-thirds said they used their fake persona as a form of escapism from their real lives. Meanwhile, one respondent said they posed as the opposite gender online to explore their own sexuality. Separately, one 2020 study of around 1,000 adults in the US – and published in the Sexual and Relationship Therapy journal – found that people with an anxious attachment style are more likely to catfish, in a bid to “exert more control over their self-presentation, make themselves more desirable, and ultimately limit the potential of relational disappointment”.

While Connor’s actions had a real, tangible effect on Erika’s life, he won’t face any consequences. He could even find another victim if he wants. This is largely because UK law does not currently offer any provision for most victims of catfishing. One recent ruling, however, can help us understand how the law treats deception in romantic relationships. In 2018, an environmental activist lost an appeal to the High Court after the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) said it would not prosecute an undercover police officer who she had a relationship with while he’d posed as a fellow protestor. The woman, granted anonymity under the name Monica, said she would “never” have consented to a relationship with officer Andrew James Boyling had she known his true identity. But the High Court upheld the CPS decision not to prosecute Boyle for rape, indecent assault, procurement of sexual intercourse and misconduct, because it found the deception “was not as such as could vitiate consent”.

Sandra Paul, a partner in criminal litigation at Kingsley Napley, says bringing cases of catfishing to court would require the law to be able to differentiate which deceptions are important enough to prosecute. “Being disappointed because somebody isn’t the person that you think they are is difficult for the criminal law to deal with,” Paul says. “Are we asking the law to get involved in the minutiae of our relationships and manage them for us? And if so, how would we decide what is criminal conduct, and what is just not being a nice person?”

In the weeks after Erika discovered Connor was lying about his identity, both her personal and professional life suffered. In the final year of her master’s degree, she struggled to complete her thesis on time, and on some days, she felt too anxious to go to work. Dr Hew Gill, a chartered psychologist and member of the British Psychological Society says the severity of stress will depend on how much the catfisher knows about the victim. “If a catfisher was willing to lie to you, then they are probably willing to break the implicit or explicit promises to keep your secrets secret,” Gill says. “These feelings may last a long time, but for most people they will eventually pass. Fortunately, the old adage that time is a great healer is usually true, and over time the intensity of emotions tends to subside as painful events recede into memory.”

Two months on from discovering the truth about Connor, Erika is still going through the motions of grieving the bond she thought she had found with him. Some days she feels better; glad that she’s no longer searching for answers and agonising over her doubts. Other days she gets angry at herself for missing glaring red flags. As for the future of her love life, Erika says she refuses to meet someone online. “If I’m going to meet someone, I’m going to meet them physically, and face to face. Never again.”

*Names have been changed

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks