The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘Memento mori:’ The benefits of thinking about your own death

Our automatic reaction is to not think about death. It is a sad and scary topic and your own death is often hard to fully comprehend but this nun is bringing the practice back, believing it can focus you on the present, writes Ruth Graham

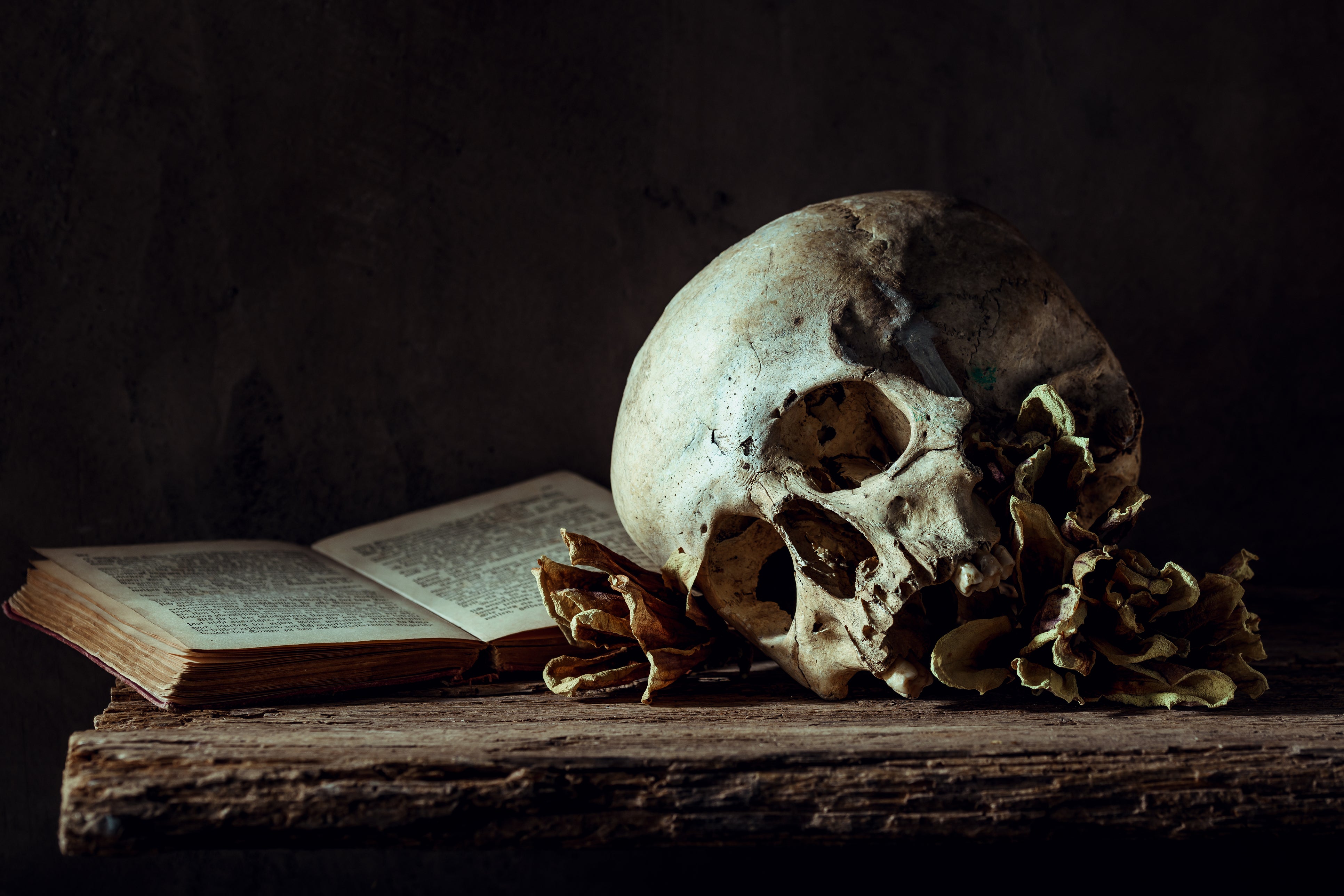

Before she entered a convent in 2010, Sister Theresa Aletheia Noble read a biography of its order’s founder, an Italian priest who was born in the 1880s. He kept a ceramic skull on his desk as a reminder of the inevitability of death. Aletheia, a punk fan as a teenager, thought the morbid curio was, “super punk rock,” she recalled recently. She thought vaguely about acquiring a skull for herself one day.

These days, Aletheia has no shortage of skulls. People send her skull mugs and skull rosaries and share photos of their skull tattoos. A Hallowe’en fancy dress ceramic skull sits on her desk. Her social media name includes a skull-and-crossbones emoji.

That is because since 2017, she has made it her mission to revive the practice of memento mori, a Latin phrase meaning “Remember your death”. The concept is to intentionally think about your own death every day as a means of appreciating the present and focusing on the future. It can seem radical in an era in which death – until very recently – has become easy to ignore.

“My life is going to end and I have a limited amount of time,” Aletheia says. “We naturally tend to think of our lives as, kind of, continuing and continuing.”

Aletheia’s project has reached Catholics via social media, a memento mori prayer journal and even merchandise emblazoned with a signature skull. Her followers have found unexpected comfort in grappling with death during the coronavirus pandemic.

The practice of regular meditation on death is a venerable one.

Becky Clements, who coordinates religious education at her Catholic parish in Louisiana and has incorporated the idea into a curriculum used by other parishes in her diocese, says “Memento mori is: Where am I headed; where do I want to end up? Memento mori works perfectly with what my students are facing, between the pandemic and the massive hurricanes.” Clements keeps a large resin skull on her own desk, inspired by Aletheia.

Aletheia rejects any suggestion that the practice is morbid. Suffering and death are facts of life; focusing only on the “bright and shiny” is superficial and inauthentic.

“We try to suppress the thought of death, or escape it, or run away from it because we think that’s where we’ll find happiness,” she says. “But it’s actually in facing the darkest realities of life that we find light in them.”

The practice of regular meditation on death is a venerable one. In the sixth century, St Benedict instructed his monks to “keep death daily before your eyes”. For Christians such as Aletheia, it is inextricable from the promise of a better life after death. But the practice is not uniquely Christian. Mindfulness of death is a tradition within Buddhism and Socrates and Seneca were among the early thinkers who recommended “practising” death as a way to cultivate meaning and focus. Skeletons, clocks and decaying food are recurring motifs in art history.

For almost all of humanity, people died younger than we do, more frequently died at home and had less medical control over their final days. Death was far less predictable and far more visible. “To us, death is exotic,” said Joanna Ebenstein, founder of Morbid Anatomy, New York, that offers events and books focused on death, art and culture. “But that’s a luxury particular to our time and place.”

The pandemic, of course, has made death impossible to forget. Since last spring, Ebenstein has conducted a series of memento mori classes online, in which students explore the global history of representations of death and then create their own. Final projects have included a miniature coffin, a series of letters to be delivered post-mortem and a deck of tarot cards composed of photographs taken by a husband who recently died. “For the first time in my lifetime, this is a topic not just interesting to a bunch of hipsters,” Ebenstein says. “Death is actually relevant.”

The Daughters of St Paul, Aletheia’s order, was founded in the early 20th century to use, “the most modern and efficacious means of media”, to preach the Christian message. A century ago, that meant publishing books, which the group still does. But now “modern and efficacious” means something more and many of the women are active on social media, where they use variations on the hashtag #MediaNuns. In December, Aletheia appeared in a video created by the order, which posed cheeky Catholic matchups like evening prayer vs. morning prayer and St Peter vs St Paul. The video, set to Run-DMC’s “It’s Tricky”, was viewed more than 4.4 million times.

As a teenager in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Aletheia, 40, listened to the Dead Kennedys and attended punk gigs. Her parents were committed Catholics; her father has a doctorate in theology and worked for a local Catholic diocese for a while but she was sceptical and declared herself an atheist as a teenager, rather than go through the formal process of joining the church.

At college, she was the leader of an animal rights club but she blanched at the animal rights movement’s arguments against “speciesism”. It seemed to her that there was a real, if difficult to define, difference between humans and other animals. But she recalls: “As a materialist atheist, I really couldn’t find a reason for that. I had this intuitive sense that the soul existed.”

While working on an organic farm in Costa Rica she had a sudden and dramatic conversion experience: God was real and she had to figure out his plan for her life. When her boyfriend picked her up from the airport after the trip, she broke up with him and cancelled her plans to go to law school. Within four years, she was wearing a habit at the convent, an unassuming blond-brick building that includes a publishing house, gardens and a small free-standing burial chapel where the nuns are entombed on death.

Aletheia began her memento mori project on social media, where she shared daily meditations for more than 500 days in a row. In October 2018, on her 455th day with the skull on her desk, she wrote, “Everyone dies, their bodies rot and every face becomes a skull (unless you are incorrupt).”

At first, she had no particular goal beyond keeping herself committed to her own daily practice but the posts were a hit and the project expanded. Now the order sells vinyl decals and hooded sweatshirts emblazoned with a skull icon designed by Sister Danielle Victoria Lussier, another Daughter of St Paul. Aletheia continues to promote the practice on social media and she has published a memento mori prayer journal and a devotional that opens with the sentence, “You are going to die”.

The books have become some of the order’s bestsellers in recent years – a boost to the nuns, whose income as a not-for-profit publisher has declined sharply. Aletheia is working on a new prayer book for Advent.

Read More:

Christy Wilkens, a Catholic writer and mother of six from Texas, says: “She has such a gift for talking about really difficult things with joy. She’s so young and vibrant and joyful and is also reminding us all we’re going to die.” Wilkens credits memento mori with giving her the “spiritual tools” to grapple with her nine-year-old son’s serious health problems. “It has allowed me not exactly to cope, but to surrender everything to God,” she says.

For Aletheia, having spent the previous few years meditating on mortality helped prepare her for the fear and isolation of the past year. The pandemic has been traumatic, she says. But there have also been small moments of grace, like people from the community knocking on the door to donate food to the nuns in isolation. As she wrote in her devotional: “Remembering death keeps us awake, focused, and ready for whatever might happen – both the excruciatingly difficult and the breathtakingly beautiful.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks