The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘How rejection sensitivity dysphoria almost killed me’

After a lifetime of experiencing every perceived slight as physically painful, Alex Partridge realised that a condition tied to his ADHD could be the cause. The founder of LADBible tells Helen Coffey about the everyday challenges he faces – and explains why increased awareness is key

I like making pancakes. It’s one of the things I pride myself in being good at. One day, I decided to make pancakes for my partner, and I was very excited. I went to buy the flour, eggs and milk, and as I was stirring the ingredients, she said: “Alex, you’re stirring the ingredients in the wrong order!”

It was a throwaway comment. But I remember my euphoria and excitement for the evening instantly disappeared. I almost went non-verbal. I didn’t understand why and how there could be such a drastic change in my mood.

I didn’t come across the term RSD – rejection sensitivity dysphoria – until years later.

I was diagnosed with ADHD in 2023, and soon after, started a podcast called ADHD Chatter. I started interviewing everyone I could find. There were lots of familiar stories that came up about this extreme emotional response to perceived or real criticism; that really triggered my awareness of it. Then I started speaking to experts on the topic.

I had an awakening on my journey doing the podcast. The more I interviewed people, the more I recognised my own behaviour, my own vulnerability, to real or perceived criticisms. I discovered there was a name that had been put to it.

A psychiatrist called William Dodson in America first coined the phrase rejection sensitivity dysphoria after recognising that there was a pattern of behaviour in his patients who have ADHD and autism, and other neurodivergent conditions.

RSD is a heightened emotional pain response to perceived criticisms from other people. And it is physically painful. You feel it in your gut sometimes – it’s instant and it’s visceral. It can be completely derailing, to the point where you’re having a reasonably nice day and a tiny little comment, or something as benign as a thumbs up emoji in response to a text – anything that’s not overtly positive – makes you catastrophise. You assume the worst-case scenario, and you think that person hates you and that you’re a nuisance to them.

And it doesn’t always need to involve verbal comments, either. It can be an eye roll at the dinner table, or you putting an idea forward and it being dismissed and ignored.

It is very damaging because when you live your life in fear of that horrible pain, you end up putting things around yourself to protect yourself from it. That can look like always putting other people’s needs ahead of your own, doing everything to such a high standard that you shield yourself from any criticisms, or just not trying. You don’t start stuff. You avoid doing things because it feels safer to stay within your comfort zone. After all, the chance of you getting criticised if you do that is a lot smaller. It’s a horrible thing, and it seems to be very prevalent in people who have neurodivergent conditions.

RSD seems to start in childhood. The obvious example for me was not being chosen for the sports team at school, or being left out of a game of “It” on the playground: little things that a lot of the time have reasonable explanations. I remember on one particular occasion when I was not chosen, feeling that intense sadness and removing myself from the situation, finding a little corner in the playground and just rocking back and forward. It’s a very shameful experience.

Neurodivergent kids are exposed to so many more criticisms than the average child. Dodson theorised that you can actually put a number on it: he estimated that it adds up to 20,000 extra comments, 20,000 extra little micro-criticisms in your early years if you are “different”.

You assume the worst-case scenario, and you think that person hates you

My first memory of feeling different was in the playground. Someone said, “You could be one of the cool kids if you weren’t so weird.” Those comments and criticisms compound over a childhood to create an adult who is so ashamed of who they are that they hide it.

You end up abandoning yourself. When someone does criticise you, it feels like, in that moment, all your effort of masking has gone to waste. You’re so fearful of your true self, which was told so many times when you were younger that there’s something wrong with you; you’re so scared of that being exposed.

You hide yourself in fear of being triggered. I know it’s a medical term, but it’s the word I use. When you do experience that intense pain, it does feel like a trigger – you instantly fill with sadness, sometimes rage. Shame is there all the time. I had a brilliant guest on my podcast, Dr Samantha Hiew, who has a PhD on the topic; she theorised that all of those comments compound to create a brain that is similar to that of someone who has complex PTSD.

The comments that I and many people in my community and I relate to are: “You’re too sensitive”; “You’re too dramatic”; “Why are you so emotional?” It’s such an underdiscussed aspect of the neurodivergent experience, but one that I think is the hardest. Because it’s the one that does the most damage, when you’re going through your life tip-toeing around the possibility of experiencing the pain that comes with rejection, you make decisions that aren’t good for you but are often good for other people instead.

I would say that RSD nearly killed me. I started a business when I was at university, a website called UNILad. I always prefer to work on my own – I’ve never particularly been a social person – but the business got to a point where I might have needed help. I ended up meeting these two potential business partners. I remember the day very well; my intuition was telling me: walk away. This is not a good idea. You don’t want to work with these people. You’re better on your own.

It’s very clear that that particular day in 2013, the people pleaser in me, the version of me that’s always been terrified of confrontation, just signed the bit of paper put in front of me. Ultimately, it triggered a five-year court case that tipped me into alcoholism and many hospital visits.

If you can hold it out in your hand and name it as RSD, you can disarm it a lot

On one occasion, the nurse told my mum that if I’d had one more drink the night before, I’d have suffered from acute alcohol poisoning – that it most likely would have ended my life.

In the end, I won the court case and got the company back. But it would have all been avoided had I listened to that intuition and said “no” instead of saying “yes” and signing a bad business contract. That’s my story, but so many people I speak to with RSD have their own. They get into bad relationships. For example, at the start of a relationship, you feel that it’s not right and it’s toxic and not a good fit for you. I think it can make many people with neurodivergent conditions very vulnerable, because you never want to say no to someone.

Relationships can be really hard regardless, because there will be real moments of tension. Unless there’s clear communication, even neutral comments will be very painful to someone with RSD. Real criticisms can be totally destructive and lead to very impulsive decisions in the moment. Decisions like: “I want a divorce”, “I’m leaving you”. Then you come down from the heightened emotional state, and often you didn’t mean what you said, because you weren’t really reacting to what your partner said in the here and now. You know that if they come home and the door slams slightly heavier, or you sense a slight abruptness in their voice, that they probably had a bad day at work – but you internalise it. You think it’s about you.

I think RSD has to be spoken about more. When you don’t have a name for it, and you don’t have an understanding or an explanation behind these big, volatile swings in emotion, it can be a car crash – a trail of relationships that you’ve left behind you. Maybe you’ve sensed or perceived a criticism from a partner, and it just felt safer to leave the relationship rather than wait for them to abandon you, all because they asked if you could talk later.

I’ve spoken to 300 experts now on ADHD, and nobody has really got a solution to the immediate effect of RSD, that moment of trigger and intense emotion. There seems to be no antidote. But what does help a lot is, when you are experiencing that moment, to recognise what it is – to call it out and say: “This isn’t me. This is RSD. I’m not responding to what that person has said today. My nervous system has been snapped back to those horrible 20,000 comments.” I truly believe it’s a trauma response.

There is no easy fix, but I think it’s about having awareness and tools. If you can hold it out in your hand and name it as RSD, you can disarm it a lot. When you have an awareness and you know what you’re dealing with, you can then also isolate and see the consequences of it, which you might have previously thought were because you’re “broken”. When you start realising that you’re not broken, you’re just different – you’re not actually “too sensitive”, you have RSD – you can then start working towards putting systems in place to help you stop people pleasing so much, or stop overworking.

Or you can start putting yourself forward for opportunities – because you absolutely deserve to do amazing things.

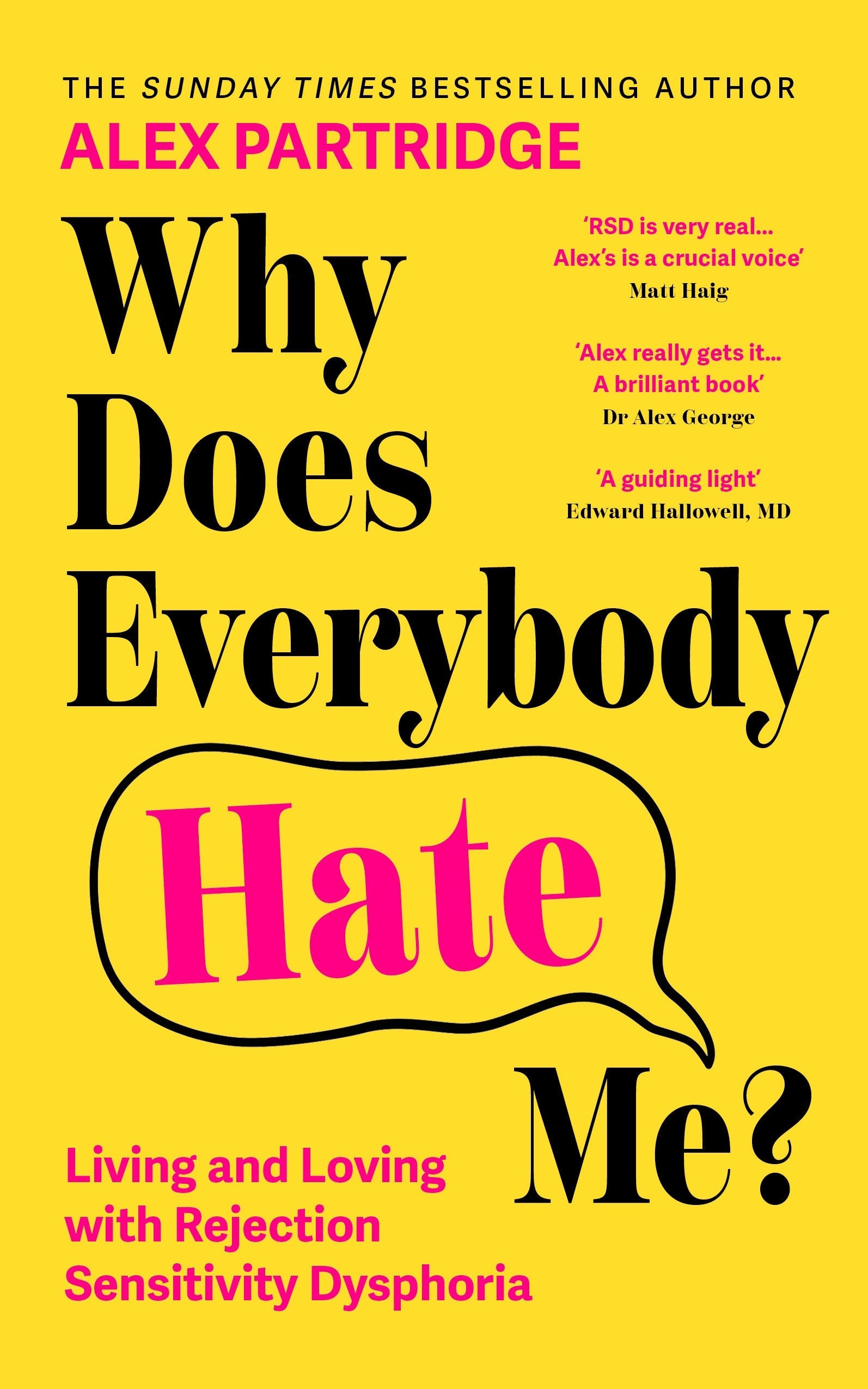

Alex Partridge is the host of the ADHD Chatter podcast and a Sunday Times bestselling author. His new book, ‘Why Does Everybody Hate Me?: Living and Loving with Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria’ is available to pre-order now (Sheldon Press, 24 March, £16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks