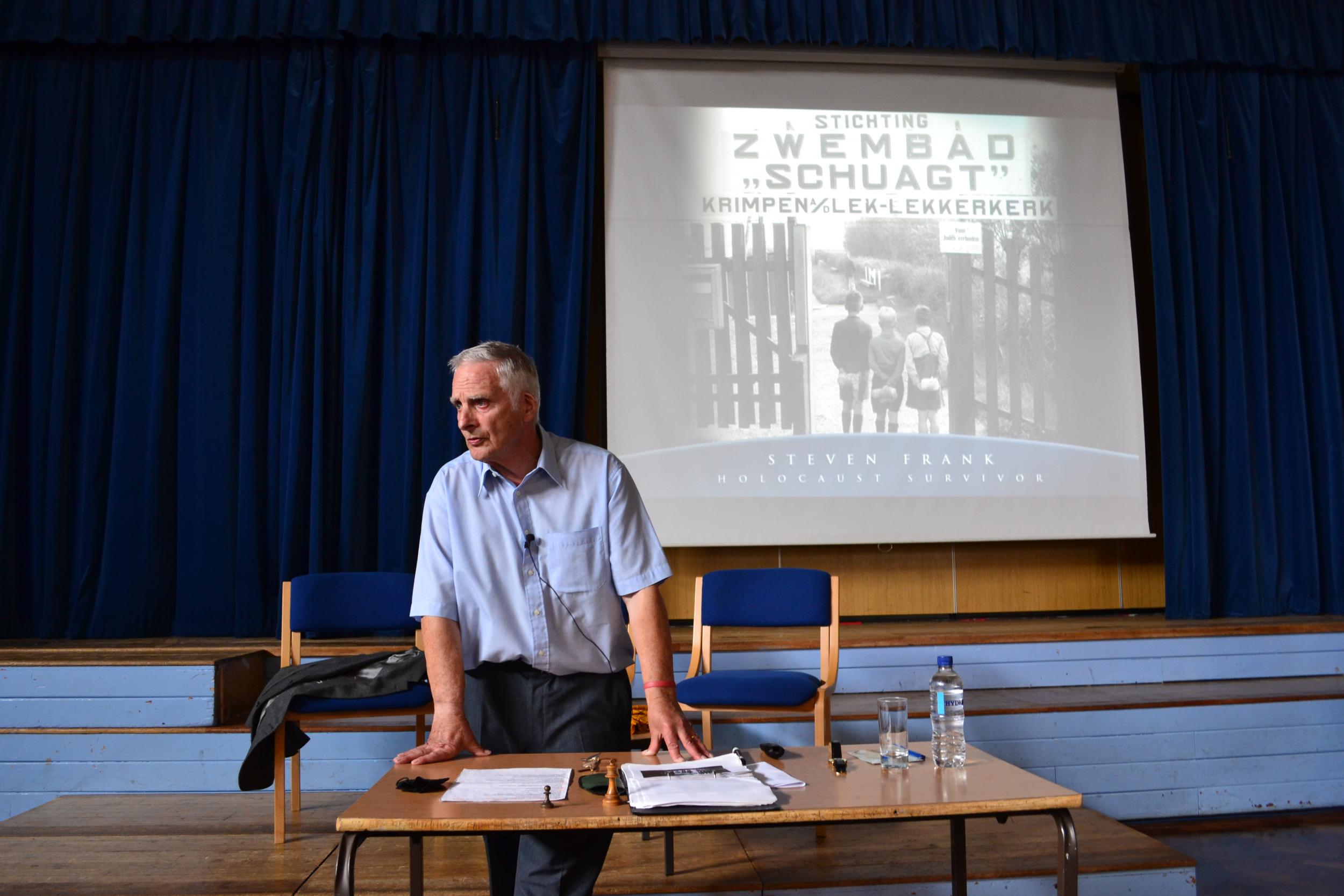

‘While others celebrated in the streets, I spent VE Day in a concentration camp wondering if I might be sent to the gas chamber’

Three quarters of a century after the Nazis finally surrendered to Allies, Steven Frank tells Alexandra Jones his tale of a day like no other

Steven Frank, 84, is a survivor of the holocaust. On VE Day in 1945 he was being held at Theresienstadt ghetto-camp in Czechoslovakia with his mother and older brother. Seventy five years on he shares his story with Alexandra Jones.

In the years since the war I have seen photographs: young people dancing in the streets, happy crowds waving flags outside Buckingham Palace, trestle tables heaving with food at street parties – for most, VE Day was a moment of pure elation.

For me, this day 75 years ago was quite a different experience.

At the time, I was in Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia with my mother and older brother; we were too weak or ill to feel elated. And too afraid.

When we’d arrived at the camp in September 1944, my mother volunteered to work in the hospital laundry. By that point, a typhus epidemic was ravaging the camp’s population and she knew that the only way to keep us safe was to stay as clean as possible. When the officers weren’t looking she would wash her children’s clothes. She also washed others’ clothes and bartered that for food – collecting crumbs of bread in a pan, adding water to make a paste and feeding us the paste to keep us alive.

On the afternoon of 8 May 1945, when she was walking back to her barrack, she was approached by two Russian prisoners of war. Though they couldn’t speak English, they motioned for her to follow them, taking her to an attic in their barrack where they’d rigged up a radio. They handed my mother a pencil and paper. They knew something important was about to be broadcast but they didn’t know what it was. When it crackled to life, she heard the voice of Winston Churchill: “...Yesterday morning, at 2.41am, General Jodl, the representative of the German high command...signed the act of unconditional surrender of all German land, sea and air forces to the allied expeditionary force...hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight tonight.”

She was astounded by what she heard; the war was over. Far from celebrating though, the three sat for a minute in anxious silence. There were still six long hours to go until midnight; would we be gathered into the gas chamber and murdered before we could be freed?

***

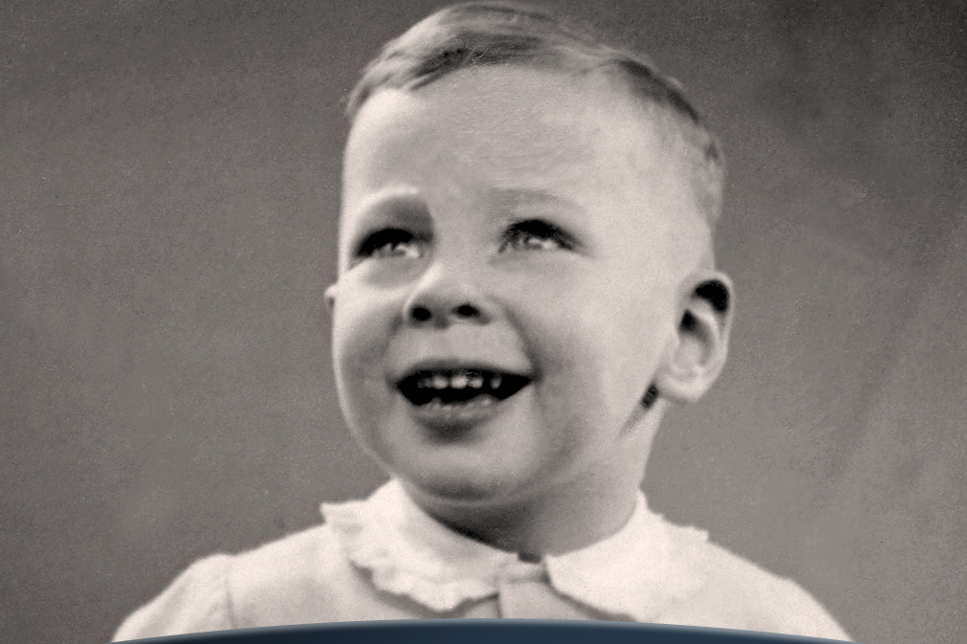

I was born in Amsterdam in 1935, the middle of three sons. My mother Beatrix had been born in Eastbourne and met my father Leonard, an eminent lawyer, in Holland when she was studying. They married in 1931.

I was five years old when the Netherlands were invaded in May 1940. Seeing the German soldiers marching through the streets in their uniforms, with their rifles on their backs, was exciting for me. I had no concept of the machinery of war and of the horrors that lay ahead. Quite suddenly though, my life changed completely. I was moved into a Jewish school and made to wear a star. I was no longer allowed to go into public parks or go to sporting events – Ajax was my favourite football team and this seemed a bitter blow.

There were still six long hours to go until midnight; would we be gathered into the gas chamber and murdered before we could be freed?

I didn’t realise it at the time, but my parents’ lives changed even more dramatically. After the invasion, my father joined the Dutch Resistance, helping to organise falsified exit papers so that Jews could escape into Switzerland or finding places for Jewish people to hide – sometimes even hiding them in our own home. There was a precarious kind of a stasis for a year or so, but eventually my father was betrayed.

In October 1942 he was arrested in his office and imprisoned. My mother, ever resourceful – and it always amazes me how she managed to keep body and soul together – at one point visited him in prison, disguised as a man, after having changed places with one of the cleaners there. Though some prominent non-Jewish friends petitioned the German government on behalf of my father, he was tortured in prison and eventually sent to Auschwitz where he was murdered in the gas chambers on 21 January 1943.

In March 1943, my mother, brothers and I were taken as a family to Barneveld, and then in September to the Westerbork transit camp, where we were held for a year. Two particular memories of this place stand out.

One time in Westerbork when I was about eight, I wandered off on my own. I wandered as far as the parameter wire – across about 100m of open space – and when I looked up I saw a guard peering down at me from his tower. Along the wire, two more guards stood with an Alsatian dog. I froze; I looked at them, they looked at me and unleashed the dog. It came bounding towards me – I put my arms up in front of my face to protect myself but was bitten all over. The whole time, the guards stood there laughing.

Another memory from the camp is of a lovely elderly Dutch couple, probably in their fifties at the time, who were in our barracks. They were both great Anglophiles and would talk to my mother in English about happy holidays they’d spent in England. One day in early 1944, I walked into the barrack and there was this howl from the sky – wheeeeew and then rat-a-tat-tat-tat-tat. I suddenly saw holes appearing in the roof and all around me pandemonium erupted – people were running and screaming. I instinctively ran across the room. I must have run through a hail of bullets but managed to escape without even a scratch. When I got to the other side I saw that the kind, adorable man was slumped face down, riddled with holes, blood pouring out of his body in streams. It was the first time I’d ever come face to face with death. And it was the death of someone I’d come to love. The sad thing of course was that this man who loved England so much was killed by British bullets fired from a British aircraft. The intelligence was wrong – they’d got the wrong place and our barracks was completely destroyed.

In September 1944 we were sent to Theresienstadt ghetto-camp in Czechoslovakia. We were transported in cattle trucks, 39 hours with no food, water or sleep. It’s hard to describe the stench that built up – human sweat, vomit, faeces, urine, all mixed in together. When we eventually arrived in Theresienstadt, and they slid open the doors it felt like taking your first breath of air after being under water for far too long.

Outside the war was coming to an end, but in the camp we had no concept of this – food was almost non-existent and we were weak. My brother was struck down with scarlet fever, and I got the mumps and fell into a coma for three days. In amongst the pain and misery, though, the children found ways to keep themselves hopeful. Some of them, for instance, found out where the Germans were throwing away their torch batteries and we managed to get hold of old torch bulbs. We would take the battery and put it between our thighs at night when we went to sleep. And the warmth of our bodies would regenerate them sufficiently for us to run one end of the bulb wire around one end of the battery, and the other around another end – so that the bulb would light-up. I remember imagining that little bulb as a bright star in the sky. Suddenly I was transported inside that bulb, and it was summertime, back in Holland. Of course it didn’t last long - slowly the bulb would dim until all that was left was a little red glimmer and reality came rushing back.

***

That reality would change from 9 May 1945 when we woke to find that the German army had deserted and been replaced by Russian forces. Theresienstadt was one of the last camps to be liberated – though that proved to be a blessing in a way. When the British liberated Belsen and the Americans liberated Buchenwald, these battle-hardened soldiers had been confronted by something they’d never seen before in their lives – skeletons begging for food. But that was the worst thing for them – many died because their stomachs burst, they couldn’t take the food after so many years of malnutrition.

We spent a month in Theresienstadt after the war under the care of the Red Cross, as they battled the typhus epidemic and reintroduced food to the survivors. Then people began to be released to their home countries. My mother though, thinking – quite rightly, as it turned out – that there would be no one we knew left alive in Amsterdam, petitioned to the Red Cross to be allowed to return to her family in London.

Though they told her "no" several times, we were eventually put on a vehicle bound for Pilsen, from where we might have the opportunity to fly to the UK. By the time we got to Pilsen it was dark. We were taken into this huge hangar, lit by arc lights – and I imagine this is what it must be like walking into hell. The hangar – a camp for displaced people – was full of bodies, all moaning, crying, groaning; so many poor people who’d lost their minds, didn’t know who they were, or where.

My mother was told by an American soldier that only the French were being sent on repatriation flights, but she fought against it. Eventually the soldier took pity on her and her two sons. This, almost two months after VE Day, was how we finally ended up back in England.

When I got to the other side I saw that the kind adorable man was slumped face down, riddled with holes, blood pouring out of his body in streams

Every VE Day I ask myself, “why was I allowed to live?” Some 15,000 children went to Theresienstadt – and less than 100 survived. Why me? How did I come out of the coma when I had mumps? How did I run through a hail of bullets, without being shattered? I went on to become a scientist. But I didn’t invent any great chemical process, I never got the Nobel Prize, I wasn’t a brilliant academic. I was just an ordinary guy, doing an ordinary job. So I often still wonder – what was the purpose of me being allowed to live?

Since retiring I’ve been sharing my story as much as possible so that future generations would know of the horrors wrought during that war and would remember the millions of lives lost.

VE Day was only possible because so many soldiers and civilians died. They all died so that we could have 75 years of virtually uninterrupted peace and freedom. The coronavirus pandemic has been one of the only times since then that our freedom has been curtailed – and perhaps that makes it the perfect moment to reflect on what living without it could truly mean.

With special thanks to the Holocaust Educational Trust

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks