The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Why we should stop using full stops - period.

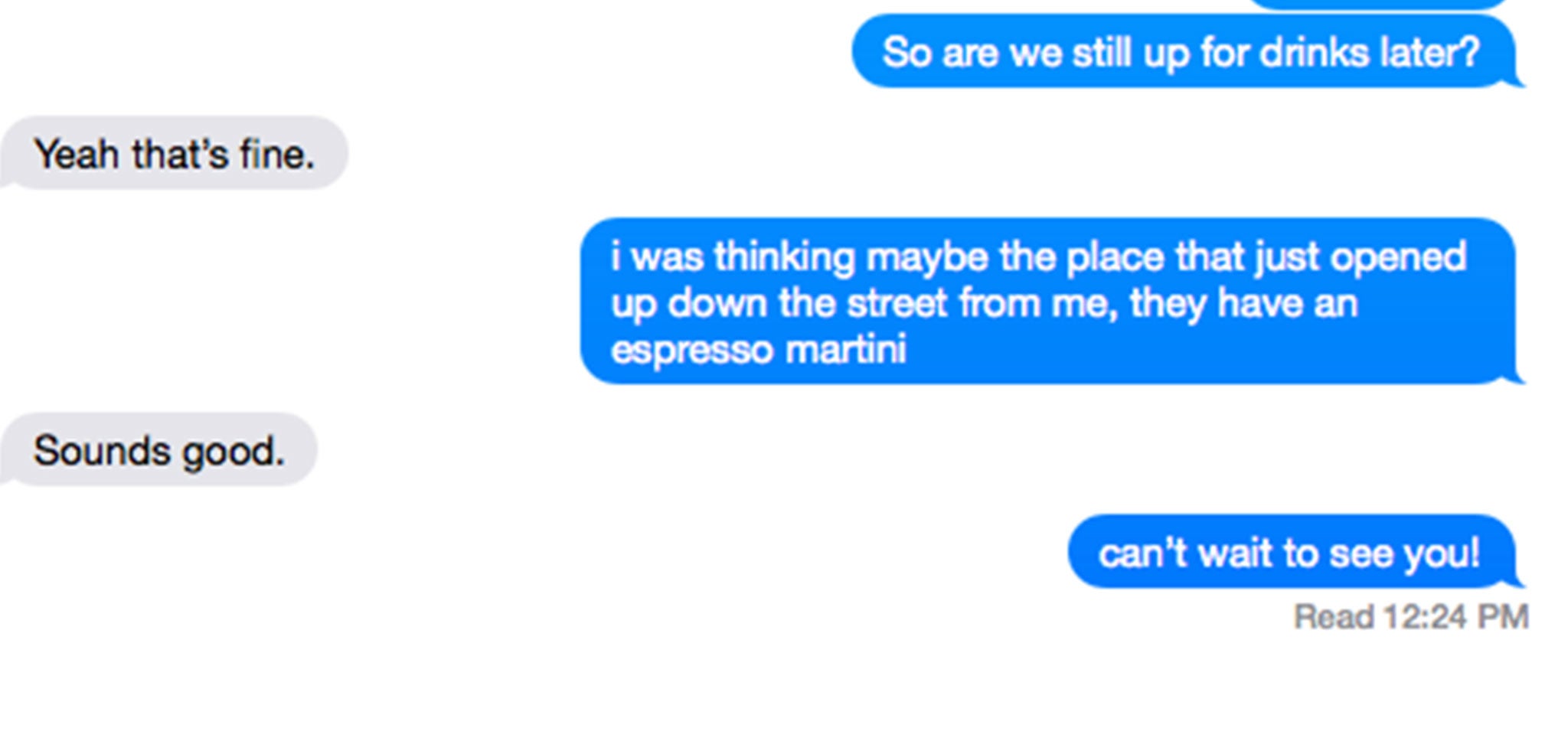

Have you ever watched parents try to text with their children? One hilarious type of misunderstanding goes like this:

Parent: I am waiting for you in the car.

Child: r u mad?

Parent: I am not mad.

Parent: I am telling you I am waiting.

Child: what?????

The poor mom or dad doesn’t understand one of the cardinal rules of texting, which is that you don’t use periods, period. Not unless you want to come off as cold, angry or passive-aggressive.

A trend piece in the New York Times on Friday touched on this fascinating development — which, incidentally, has been brewing for at least two decades, ever since kids were logging onto AOL Instant Messenger. The period is no longer how we finish our sentences. In texts and online chats, it has been replaced by the simple line break.

You just hit send

Your words end up on a new line

a visual indication

that you have started

a new sentence,

phrase,

clause,

or unit of meaning

Of course, this practice far predates the instant message. Poets have been using line breaks for basically forever. (In the right light, you might even say a text conversation has some of the same exuberant, associative, overlapping qualities of say, an e. e. cummings poem.) But we can credit the text and the IM for making the line break the default method of punctuation in the 21st century.

The period, meanwhile, has become the evil twin of the exclamation point. It’s now an optional mark that adds emphasis — but a nasty, dour sort of emphasis. “It is not necessary to use a period in a text message, so to make something explicit that is already implicit makes a point of it,” Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist at the University of California at Berkeley, told the New York Times.

A few years ago, Ben Crair at the New Republic wrote a hilarious history of the period in age of instant messaging. “The period was always the humblest of punctuation marks,” he began. “Recently, however, it’s started getting angry.” Crair noticed that in his text conversations, the period had stopped serving any grammatical purpose. Instead, it was mostly being used to express a certain tone or emotion. And that emotion was anger.

An antique manuscript (Public domain via Wikimedia commons)

The period has essentially become a stylistic device, which is a fascinating development because it recalls the freewheeling origins of Western punctuation.

Early Greek and Latin texts often lacked any kind of punctuation. They didn’t even have spaces between the words. The reader just had to figure it out. Later on, punctuation and spacing were added to help guide novice readers.

There weren’t many rules at first. Punctuation was largely an oratorical tool, a guide to help people read a text aloud. Scholars would mark down wherever they thought it would be good for the reader to take a breath, or to adjust the tone of their voice. They would also make marks where they anticipated that people might get confused, wherever that was in the text. They didn’t end every sentence with punctuation if they thought the meaning was already clear.

For instance · medieval scribes often used something called the punctus · a dot that floated between words · The punctus was an all-purpose tool · It could separate complete sentences · functioning like a medieval period · It could also act like a comma · to separate different clauses within a sentence.

But the punctus was much more versatile than anything we have in modern written English. Scribes would liberally sprinkle punctus marks onto a sentence if they felt they would help readers understand better. Here’s an example from a medieval math text, in which the author used punctus marks to cordon off words into basic groups. (I’ve attempted to modernize some of the Middle English spelling.)

Thes · ix figures and nowmbres · eche · rekenyd · by himself · is clepid numerus digitus

These · nine figures and numbers · each · reckoned · by himself · is called numerical digits

This usage may seem weird, but we employ hyphens to accomplish a similar purpose today. “The medium green car” is an ambiguous phrase. Is the color medium-green, or is the car a medium-size car? Putting in a hyphen — “The medium-green car” — eliminates that confusion. In natural speech, we would distinguish between the two meaning by adding subtle pauses in different places. To convey the same information in medieval writing, a scribe could have grouped the words using punctus marks: “The · medium green · car.”

With the invention of the printing press and the rise of mass publishing, both the punctuation and the spelling of written English quickly became standardized. People once had the freedum too spel wurds any wey they liked. Now there were rules for spelling.

Likewise, people created rules for punctuation. Punctuation reformers demanded that the marks be placed systematically, in accordance with the underlying structure of a sentence. You couldn’t sprinkle in punctuation just for effect, as medieval scribes did. Punctuation began to serve more a grammatical function than a rhetorical one.

This remains a difficult concept for children, who instinctually use punctuation marks in writing like they use pauses in speech. But in spoken language, pauses are often stylistic, and the pauses don’t always line up with the grammar of what we’re saying. For instance, consider the following run-on sentence:

I love my cat, I can’t be without her.

This is a non-grammatical use of the comma, but it conveys something important. You get a sense of enthusiasm. When we get excited, the pauses between our sentences shrink. We speak in run-ons. There are ways of notating this with modern punctuation. A period feels too weighty, but you could a semicolon or a dash:

I love my cat; I can’t be without her.

I love my cat — I can’t be without her.

If you’re texting, though, you have another option — the line break:

I love my cat

I can't live without her

Omg

Linguists have noted that the kind of language that we employ in texts and instant messages is very similar to spoken speech; in this way, it bears resemblance to the early days of writing, when manuscripts closely followed how people actually spoke.

Recent trends in punctuation also hark back to that age, when people used punctuation in more liberal and creative ways. The modern line break is like the medieval punctus — an all-purpose piece of punctuation that inserts pauses wherever we’re feeling it. And the period has gained expressive powers after it was laid off from its job marking the ends of sentences. Now it’s an icy flourish we deploy against frenemies and exes.

We should celebrate these developments. Writing is becoming richer. This is an exciting time. Period.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks