Women of colour were crucial to women’s suffrage – it’s time we acknowledge them

Susan B Anthony and the rest of the suffragettes are hallmarked as the leaders of the movement, but the contributions of Native and African American women have been left out of the history books, says Liz Weber

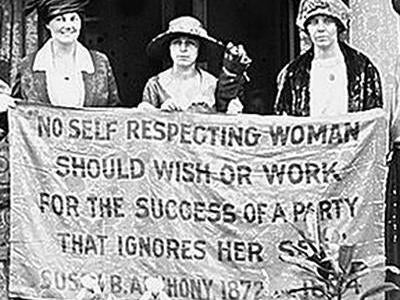

The story of the suffragist movement is usually woven with a single strand. Susan B Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Alice Paul; these are the women whose names are etched into the history books. They were tremendously influential in the effort to give women “the vote”.

But that’s not nearly the whole story. The story we remembered last week – celebrating the 100th anniversary of congress passing the suffrage amendment – ignores women of colour and their contribution to the movement’s success.

The story, experts say, is due for a reckoning.

“It didn’t start with white women, that’s not the point of entry into women having political voice,” says Sally Roesch Wagner, who received one of the first doctorates in the country for women’s studies, while at the University of California at Santa Cruz. “Indigenous women have had a political voice in their nations long before white settlers arrived.”

Wakerakatste Louise McDonald Herne, the bear-clan mother of the Mohawk Nation, says her community has a “whole different memory and experience from those of white women”.

As clan mother, Herne is charged with appointing leaders, naming members and working for the general welfare of her people. She says that despite the residual effects of colonialism, there is a huge reservoir of indigenous research, and indigenous scholars are beginning to craft their own narratives, including those of their ancestors.

“It was our grandmothers who showed white women what freedom and liberty really looked like,” Herne says. “They began to witness for themselves a freedom that they had never seen before.”

They knew these women, they spent time with them, and they wrote about them

Wagner, who is behind books such as Women’s Suffrage Anthology and Sisters in Spirit, has for almost 30 years studied the Haudenosaunee (or the Iroquois) influence on the early feminist movements. According to her research, many of the suffragists interacted with native women and saw the political power and respect they received.

“They knew these women, they spent time with them, and they wrote about them,” Wagner says. “I think that gives them the sense that we can have a different world, we can be treated differently.”

The suffragist story is long and twisted. The organised movement lasted from 1848, with the first women’s rights convention in New York, to 1920, when the amendment was ratified by 38 states. In other words, it took almost 70 years – three generations of women and advocates – before it was law.

The Native American influence on the movement can be traced to the Seneca Falls convention of 1848, which is considered to be when the effort began. For two days, activists gathered in the New York hamlet to draft the Declaration of Sentiments. Signed by 68 women and 32 men, the document argued that anti-women laws held no authority, declared that men and women should be held to the same moral standards, and ultimately called for women’s suffrage.

According to Wagner’s research, Mott, one of the signature drafters, spent the summer of 1848 with the Seneca Nation, one of the largest of six Native American nations that made up the Iroquois Confederacy.

“She watches the women have equal voice politically and she’s watching women have this spiritual responsibility to plan ceremonies,” Wagner says. “During this time, Mott would have seen clan mothers nominating chiefs, putting them in positions of power and removing them as necessary. It is a responsibility clan mothers still hold.

“Women have a strong position, and our society cannot move forward without the presence of women,” Herne says.

They said give women the vote because it’s a way to maintain white, native-born supremacy

While this inspiration was filtering in from indigenous women, the organisation of the suffrage movement emerged from the earlier abolition movement, according to Ellen DuBois, a history and gender professor emeritus at the University of California at Los Angeles.

But as the movement progressed, the two main suffrage organisations – the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Women’s Suffrage Organisation – merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (Nawsa) in 1890. This ultimately shifted its trajectory.

“They said give women the vote because it’s a way to maintain white, native-born supremacy,” Wagner says.

As the Nawsa expanded, the structure decentralised and auxiliary organisations in each state were given more power to do what they wanted to gain support. “Under that policy, Southern states explicitly bar black women from participating,” DuBois says.

Missing from the list of the matrons of the movement are Ida B Wells and Mary Church Terrell, according to Tammy Brown, professor of history at Miami University in Ohio.

Wells, an investigative journalist and civil rights activist, fought for racial equality on the international stage while Terrell, one of the first African American women to earn a college degree, appealed to white suffragists to acknowledge the plight of African American women, according to Brown.

Yet the state societies in the south continued to work against African American interests because they thought it was the only way to win the South, according to DuBois.

“But what if, instead, they had made an alliance with African American men who could vote and worked to strengthen their voter rights instead of denying them with Jim Crow laws?” Wagner says. “How many lives of African American men might they have saved?”

While Brown has seen an increase in the coverage of the crucial role African American women played in the fight for the vote, she doesn’t believe there has been an honest dialogue about the history of racism within women’s movements.

“We must acknowledge our fraught and often tragic history, if we want to build a stronger, more equitable society in the future,” she says.

Outside of the straight lines of a textbook, history is a hard thing to pin down. Anniversaries offer an opportunity for greater accountability, a chance to create a fuller, more detailed accounting, according to Wagner.

Herne agrees that the story has to change, and says: “There has to be a revitalisation of our voice.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks