Doctors suggest new names for low-grade prostate cancer

Some doctors say it’s time to rename low-grade prostate cancer to eliminate the alarming C-word

A cancer diagnosis is scary. Some doctors say it’s time to rename low-grade prostate cancer to eliminate the alarming C-word.

Cancer cells develop in nearly all prostates as men age, and most prostate cancers are harmless. About 34,000 Americans die from prostate cancer annually, but treating the disease can lead to sexual dysfunction and incontinence.

Changing the name could lead more low-risk patients to skip unnecessary surgery and radiation.

“This is the least aggressive, wimpiest form of prostate cancer that is literally incapable of causing symptoms or spreading to other parts of the body,” said University of Chicago Medicine’s Dr. Scott Eggener, who is reviving a debate about how to explain the threat to worried patients.

The words “You have cancer” have a profound effect on patients, Eggener wrote Monday in Journal of Clinical Oncology. He and his co-authors say fear of the disease can cause some patients to overreact and opt for unneeded surgery or radiation.

Others agree. “If you reduce anxiety, you’ll reduce overtreatment,” said Dr. David Penson of Vanderbilt University. “The word ‘cancer,’ it puts an idea in their head: ‘I have to have this treated.’”

Diagnosis sometimes starts with a PSA blood test, which looks for high levels of a protein that may mean cancer but can also be caused by less serious prostate problems or even vigorous exercise.

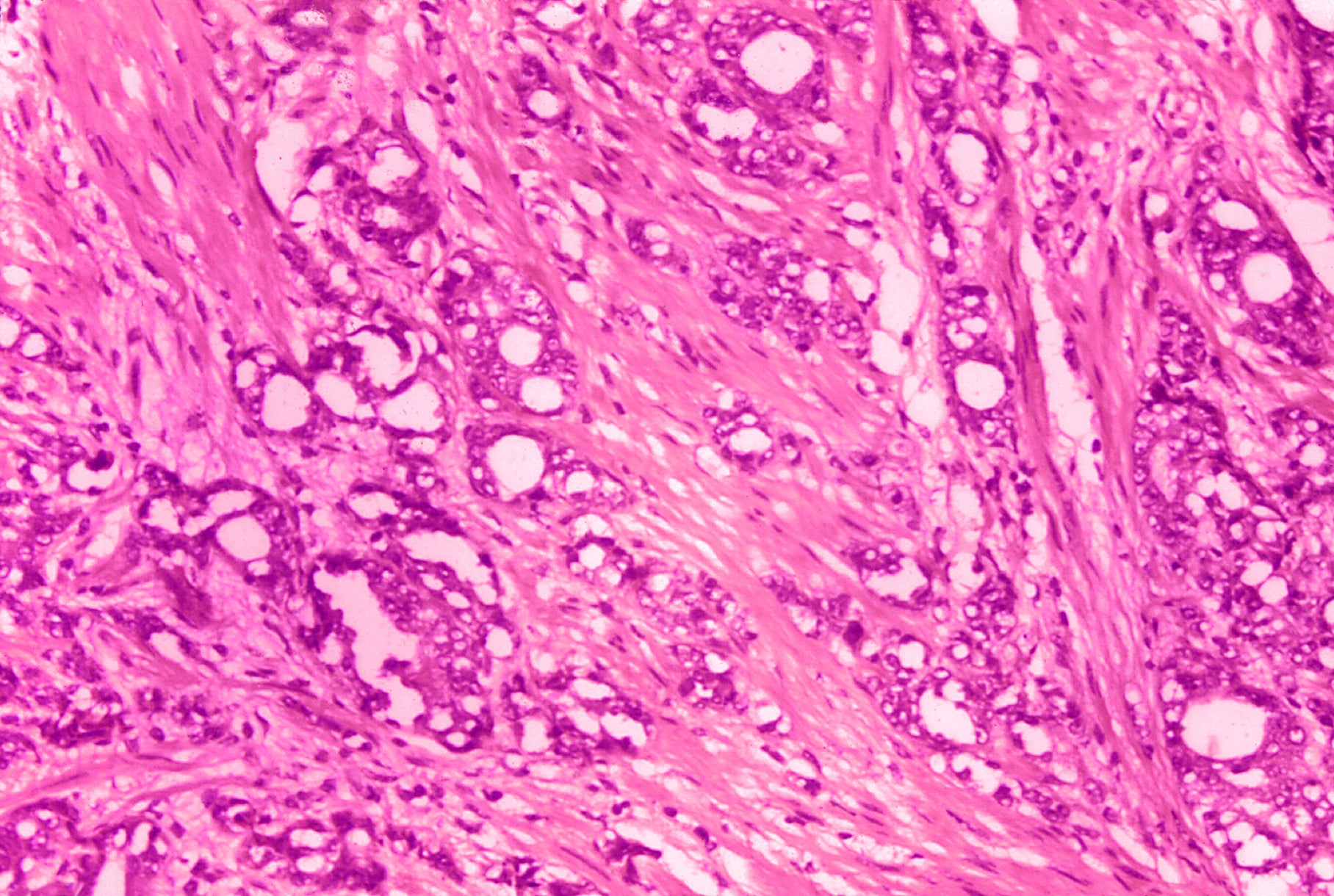

When a patient has a suspicious test result, a doctor might recommend a biopsy, which involves taking samples of tissue from the prostate gland. Next, a pathologist looks under a microscope and scores the samples for how abnormal the cells look.

Often, doctors offer patients with the lowest score — Gleason 6 — a way to avoid surgery and radiation: active surveillance, which involves close monitoring but no immediate treatment.

In the U.S., about 60% of low-risk patients choose active surveillance. But they might still worry.

“I would be over the moon if people came up with a new name for Gleason 6 disease,” Penson said. “It will allow a lot of men to sleep better at night.”

But Dr. Joel Nelson of University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, said dropping the word “cancer” would “misinform patients by telling them there’s nothing wrong. There’s nothing wrong today, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have to keep track of what we’ve discovered.”

Name changes have happened previously in low-risk cancers of the bladder, cervix and thyroid. In breast cancer, there’s an ongoing debate about dropping “carcinoma” from DCIS, or ductal carcinoma in situ.

In prostate cancer, the 1960s-era Gleason ranking system has evolved, which is how 6 became the lowest score. Patients may assume it’s a medium score on a scale of 1 to 10. In fact, it's the lowest on a scale of 6 to 10.

What to call it instead of cancer? Proposals include IDLE for indolent lesion of epithelial origin, or INERRT for indolent neoplasm rarely requiring treatment.

“I don’t really give a hoot what it’s called as long as it’s not called cancer,” Eggener said.

Steve Rienks, a 72-year-old civil engineer in Naperville, Illinois, was diagnosed with Gleason 6 prostate cancer in 2014. He chose active surveillance, and follow-up biopsies in 2017 and 2021 found no evidence of cancer.

Calling it something else would help patients make informed choices, Rienks said, but that’s not enough: Patients need to ask questions until they feel confident.

“It’s about understanding risk,” Rienks said. “I would encourage my fellow males to educate themselves and get additional medical opinions.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks