A story of love, power and money beyond the imagination of Tolstoy

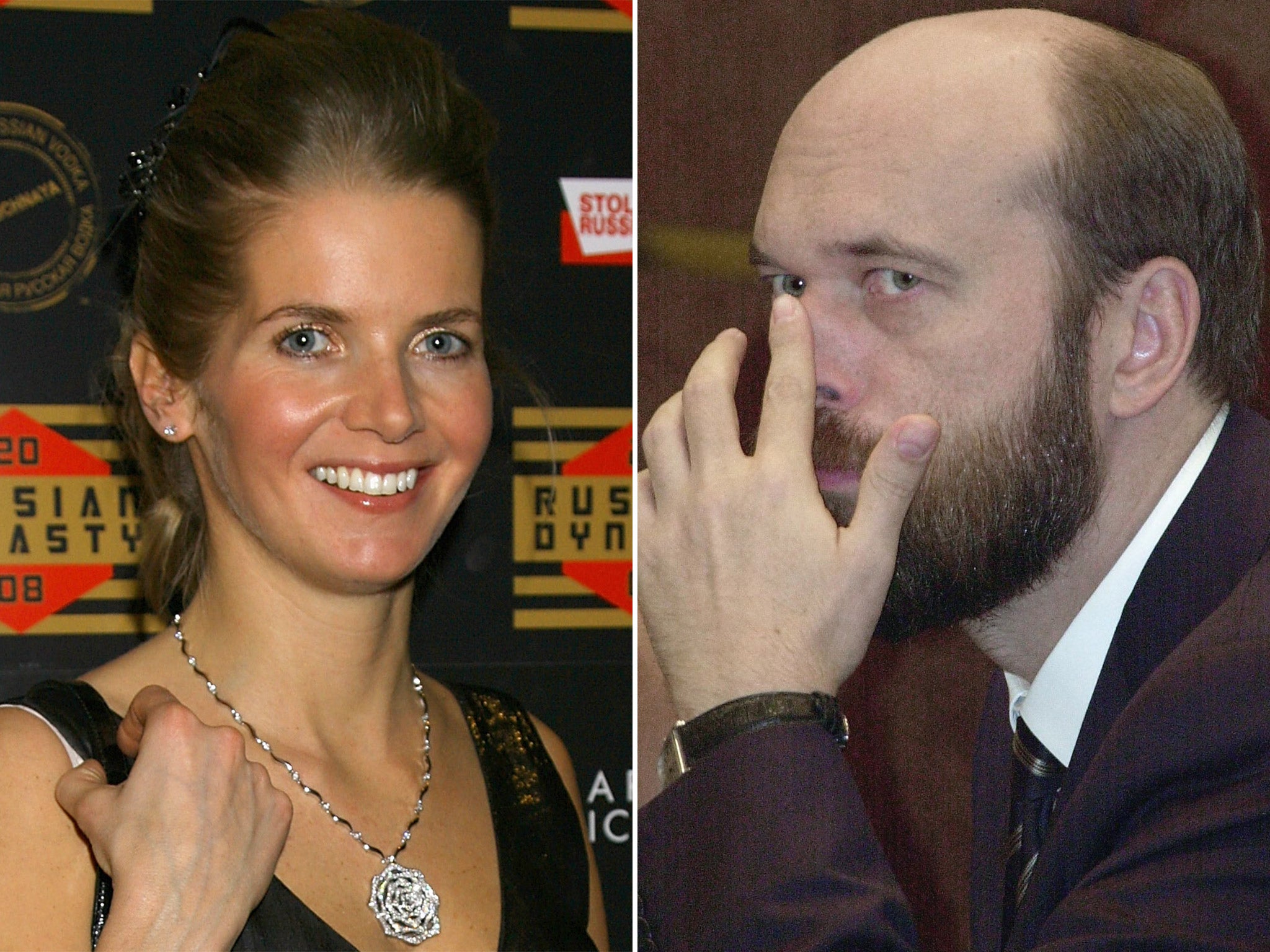

The Russian oligarch Sergei Pugachev and his English lover Alexandra Tolstoy hit hard financial times when his bank collapsed. Since the High Court froze his assets this year, they have had to live on ‘just’ £10,000 a week

For the Russian oligarch Sergei Pugachev and his English TV presenter partner Alexandra Tolstoy, this Christmas will be one of tightened belts and, who knows, maybe even a Lidl turkey.

Because, despite once being known as Putin’s banker, Mr Pugachev has fallen on hard times since the fall of his business empire. Indeed, a court order in the summer froze the couple’s assets, insisting they and their three children survive on just – get your handkerchiefs ready – £10,000-a-week.

As Ms Tolstoy, whose cut-glass accent is the product of an education at the same school as the Duchess of Cambridge, complains, it is so tough to run their two London homes and a château overlooking Nice on such an amount.

Being a distant relative of Leo Tolstoy may give you bragging rights in literary circles, but it does not pay the running costs of a stately home on the Côte D’Azur. Especially when you also have the upkeep of a £12m house in Battersea – once owned by the Forbes family – to consider too.

Ms Tolstoy’s first husband was a penniless Uzbek horseman, whom she met during a decade of travelling around China, Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan. BBC2 viewers have been treated to a documentary series, Horse People, in which she lived with remote, rural communities. But the marriage foundered and she fell in love with Mr Pugachev.

For the past two weeks he has been appealing against the asset freeze in the High Court, claiming to be down to his last $70m (£45m). The former billionaire is being sued by the Russian state liquidator, which is combing through the wreckage of his Mezhprombank – once one of the country’s biggest private commercial banks.

A slick PR campaign has accompanied his barristers’ efforts, and provided him with extensive coverage in the Financial Times and Time magazine, which have given the impression that he is a wronged businessman who fell foul of the wrath of the Russian president. In the FT, he complained: “Today in Russia, there is no private property. There are only serfs who belong to Putin.”

In Time, he pleased his American readers with tales of the Russian president’s incompetence, again portraying himself as the big business executive who got on the wrong side of an impetuous, none too bright, leader.

The truth, according to the liquidators, is somewhat different.

Mr Pugachev rose to corporate power during the 1990s as a close associate both of Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin. As Mr Putin took over the presidency, Mr Pugachev was one of relatively few oligarchs already in the former KGB man’s circle. He set up Mezhprombank in 1992 and became one of the country’s most powerful businessmen.

Fast forward to 2008, and the global financial crisis at its height. Like Lloyds, RBS and so many other banks around the world, Mezhprombank got into such difficulties that it received a bailout – of $1.15bn – from the Russian central bank.

However, according to the liquidators’ arguments, just weeks after being granted the central bank bailout, Mr Pugachev channelled $800m of the taxpayer’s funds to himself.

First of all, they allege, more than $700m of bailout funds went from Mezhprombank to a Swiss bank account in the name of a Cypriot company called Safelight. Safelight had not previously carried out any business, they allege, and Mr Pugachev’s own son, Alexander, was one of its directors.

Then, the liquidators claim, came the dividend scheme, also in December 2008. Allegedly, some $106m of the bailout funds were paid as a “dividend” into Mr Pugachev’s personal bank account.

The bailout funds were only half of it, though, the liquidators claim. They say that Mr Pugachev’s bank made more than 180 unsecured “loans” totalling $2bn to shell companies thought to be owned or controlled by him. The companies were allegedly often run by nominee directors, of the type who might be termed “cutouts”, the claim argues – real people, perhaps, but with no real involvement in the companies.

The supposed directors of these firms receiving billions of dollars in loans allegedly included Mezhprombank security guards and a pizza delivery man. The liquidators say these “directors” often were not even aware that they were directors.

Not that the $2bn was advanced with no security, of course. Mezhprombank did allegedly receive collateral, in the form of pledged ownership rights to a $2.5bn coal deposit in Siberia. The trouble was that, in August 2010, these pledges were allegedly revoked. The security on the $2bn, in other words, disappeared, the liquidators say.

Just weeks later, after a Mezhprombank default, the Russian central bank withdrew the company’s banking licence and the liquidators were brought in, only to find they had no way of getting the $2bn back, the liquidators, known in Russia as the DIA, allege.

On top of those three schemes, the DIA also contends that Mr Pugachev’s bank forwarded him further funds to buy a yacht and villa in the south of France. These loans have also not been repaid, the DIA alleges.

In his application to have the freezing order discharged, Mr Pugachev says the DIA’s claims are all politically motivated hogwash, and claims he has received threats to his family and been ordered to pay bribes, which he has refused.

He says the Russian state has conducted a targeted attack on his assets and “expropriated” billions of dollars of them on the cheap, just as it did with the oil company Yukos. All along, as he told the Financial Times, the Kremlin has been motivated by a desire to get its hands on his two St Petersburg shipyards – which he claims are the country’s biggest and most modern – at a knockdown price.

These were held as security against the bailout loans, and ownership transferred to the central bank when Mezhprombank went bust. The yards were then sold to a state-owned company chaired by Mr Putin’s lieutenant, Igor Sechin, who now heads the state oil giant Rosneft, for little over $400m.

Mr Pugachev says the accounting firm BDO valued them at $3.5bn. This, he points out, would have been ample to settle the bank’s debts to the central bank. But Mezhprombank’s liquidators claim the BDO valuation was far too generous and misconceived, saying that the prices of the sales were set by the bankruptcy court after valuations from Ernst & Young and Deloitte.

Mr Pugachev’s legal team says the $700m to his son’s company in Cyprus was not bailout money and was for a commercial investment.

The other transfers were also entirely legitimate, they say, while the revocation of the $2.5bn pledges over the coal mine was done without his knowledge. Besides which, he contends, he was busy working as a senator on behalf of a province in Siberia and put his business assets in trust. So he was not in control of the bank for many years before its liquidation.

Mr Pugachev’s appeal against the asset freeze ended in the High Court yesterday afternoon and a decision is not expected until next year.

And, struggling by on that £10,000 a month, Alexandra and Sergei will have to keep watching the pennies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments