One year to Brexit: How well has the British economy really been performing? And what can we expect next?

So just how has well or badly has the British economy performed since the country voted to Leave? And what is the best estimate of what we can expect to come next?

There is now just one year to go before the UK exits the European Union.

Before the June 2016 referendum the Treasury famously warned that a Leave vote would result in an instant UK recession.

That has not materialised, as Brexiteers frequently delight in pointing out.

But opponents of Brexit also stress that the UK’s growth has slowed dramatically since 2016.

So just how has well or badly has the British economy performed since the country, by a relatively narrow margin, voted to Leave?

And what is the best estimate of what we can expect to come as the 12 month countdown to Brexit itself begins?

Currency

The UK’s currency, of course, fell through the floor in the early hours of 24 June 2016, when it became clear that the Britons had voted to rupture their 43-year membership of the European Union.

Indeed against dollar, sterling endured its biggest intra-drop on modern record (11.9 per cent), hitting a 31-year low of $1.3679.

This currency slump was an unambiguous thumbs down from currency markets for the UK economy in the era of Brexit.

Against the dollar, the currency continued to fall in the months after the vote, bottoming out at around $1.21 in January 2017, when Theresa May made it clear that she planned to pull the UK out of the EU single market and the customs union – a pretty hardline interpretation of Brexit.

But, since then, the currency has come back quite a lot. It’s currently trading at around $1.41, around 5 per cent down on its pre-referendum peak. However, much of this recovery seems due to the weakness of the dollar, rather than the strength of the pound.

If we look at the trade-weighted value of sterling – which values the UK currency against a basket of all our trading partners’ currencies – it is still down around 9 per cent on its level on 23 June.

As to where the exchange rate is likely to go next, analysts are split. Some think it may strengthen as steady progress towards an amicable separation from the EU is made. Others insist that sterling remains highly vulnerable to a new sell-off

Inflation

Aside from pushing up the cost of foreign holidays, the most painful impact of the fall in sterling in the wake of the referendum has been to jack up the cost of living.

UK firms’ import costs rose and they gradually passed that on to consumers in the form of higher prices for goods in the shops.

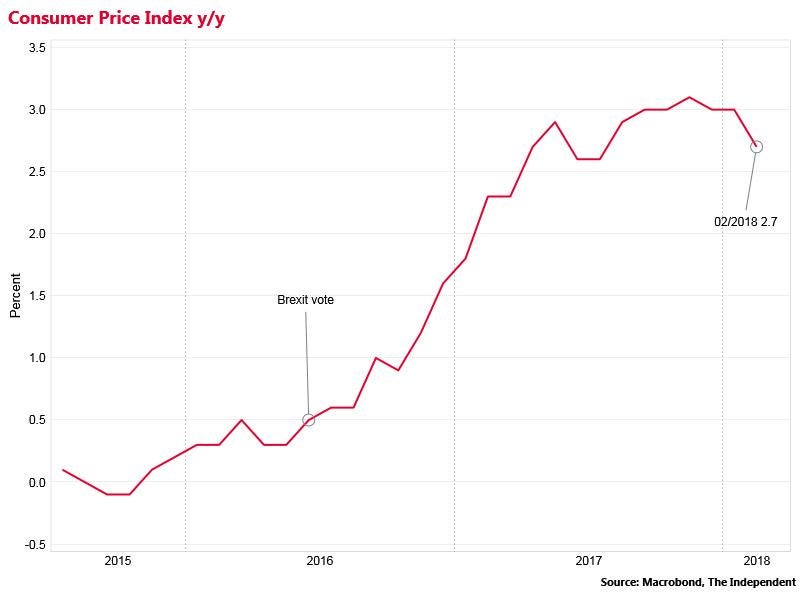

Inflation, which was running at around 0.5 per cent at the time of the vote hit 3 per cent late last year.

As prices rose faster than average wages, average UK living standards got squeezed.

As to what will happen to inflation next, most economists think the impact of the sterling slump has now peaked.

And inflation fell to 2.7 per cent in February. Adjusted for inflation, wages are expected to start growing again in the coming months, after a year of contraction.

Yet the Bank of England believes that, with the unemployment rate at its lowest since 1975 and wages on the rise, underlying inflationary pressures are building again in the economy. That is why it put up interest rates in November 2017 for the first time in a decade.

Many expect another hike in May, which will put a bit more pressure on millions of mortgage borrowers.

Further out, opinions are split on the path of interest rates. Some think the Bank will hike fairly rapidly. Others suspect that the weakness of the overall economy as Brexit saps growth will keep a lid on the cost of borrowing as set by the Bank.

Business investment

The reaction of many firms when Britain voted for Brexit was one of alarm. Most large firms think that EU membership has been beneficial for the UK economy. They also think that Theresa May’s decision to leave the single market and the customs union will be damaging for their businesses.

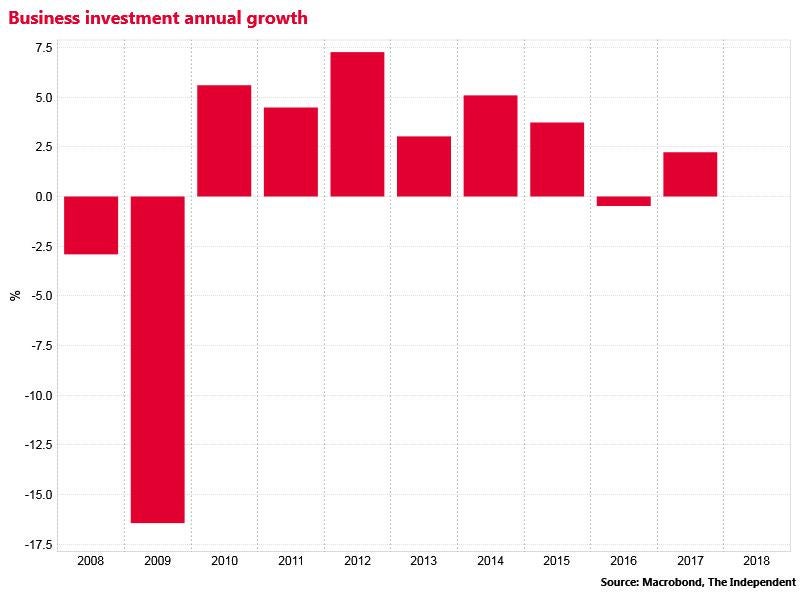

And surveys suggest this concern has hit investment, with many saying they have paused investment until the post-Brexit trade picture is clearer. This is bad in the short-term, as business investment helps drives GDP growth and national income. It is also negative for the longer-term because business investment contributes to productivity growth.

The national accounts show that business investment fell in 2016 – the first annual decline since recession in 2009. There was growth of 2.5 per cent in 2017. But this was also a year in which the global economy bounced back, meaning that, other things equal, UK investment ought to have grown much more rapidly.

Growth

Many of the worst fears prior to the Brexit vote have not come to pass, but at the same time the UK’s growth has clearly been stifled since the referendum. The quarterly GDP figures have pointed to a clear slowdown in 2017, mainly due to the negative impact of higher inflation on household consumption. Business investment has made little contribution. Nor, despite the slump in sterling, has net trade.

But the best indicator of the negative impact of the Brexit vote comes when comparing the UK to the rest of the G7. On an annual basis the UK was growing at around 2 per cent at the time of the Brexit vote. This growth rate slipped to 1.4 per cent in the final quarter of last year. But over 2017 the annual growth rates of the rest of the G7 – the US, France, Germany, Canada, Japan and Italy – all accelerated on the back of a healthier global economy. This shows the UK has gone from the top of the G7 growth table to the bottom.

One analysis by researchers from the London School of Economics estimate that the UK economy is today around £20bn smaller than where it would have been without the Leave vote – which translates to a cost of around £300m a week.

As to where GDP will go next, opinions are, again, divided. The Office for Budget Responsibility has projected 1.5 per cent GDP growth this year. But some expect it could be as high as 2.5 per cent, while others think it could be as poor as 0.5 per cent.

Next year, the year of Brexit, the OBR expects growth to sink to just 1.3 per cent growth, which would be the weakest since the 2008-09 recession.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks