Budget 2020: A decade of UK tax and spending in six charts

How have the public finances changed over that period? Where does the money raised in tax go? And what has been the impact of austerity on department spending?

The new chancellor Rishi Sunak will unveil his Budget on Wednesday.

It’s almost certain to be dominated by the government’s response to the coronavirus crisis. Yet we can also expect to get new projections for UK state spending and taxation over the course of this parliament.

It’s also roughly 10 years since Mr Sunak’s predecessor, George Osborne, unveiled his “emergency budget” which set in train a controversial policy of fiscal austerity.

So how have the public finances changed over that period? Where does the money raised in tax go? And what has been the impact of austerity on public service spending?

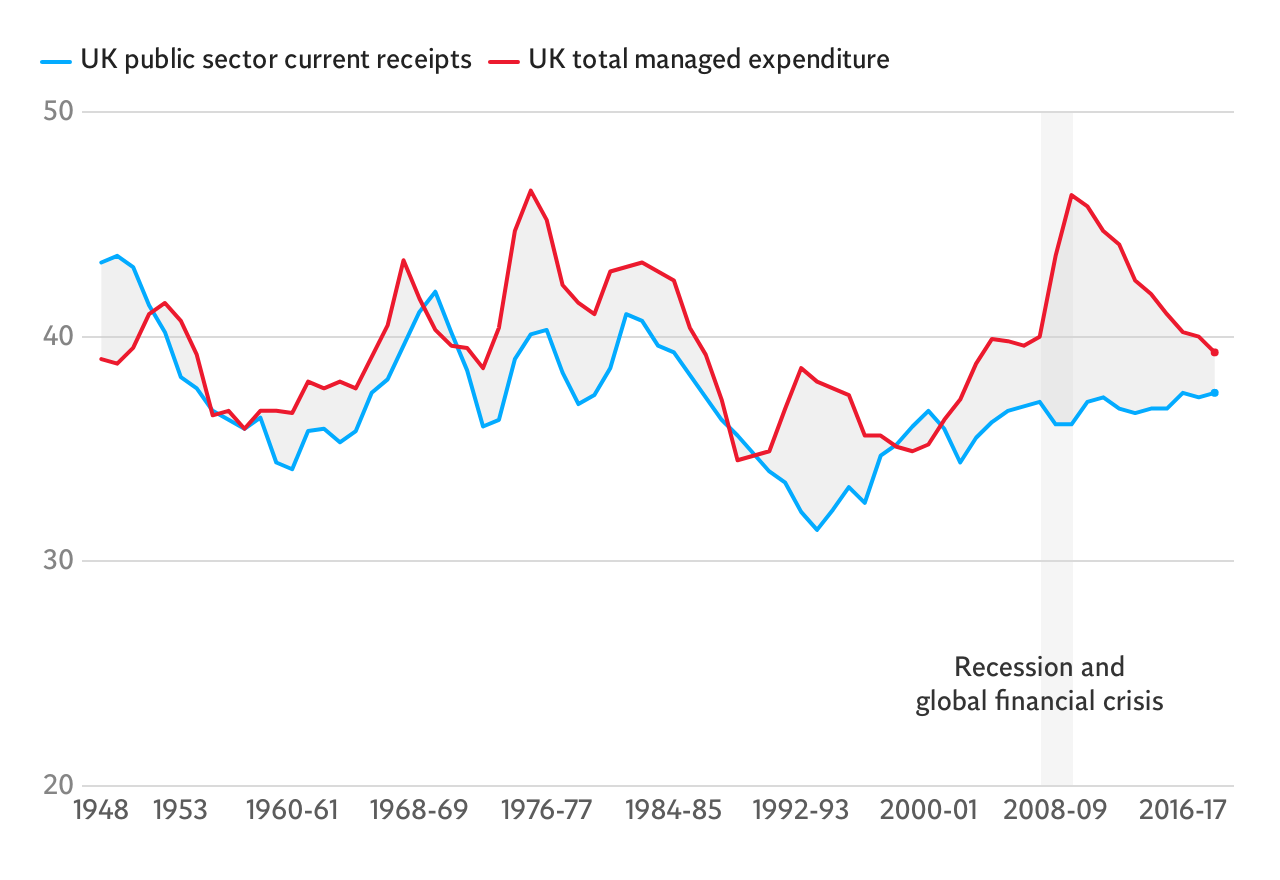

A spike in spending as a share of GDP

During the 2007-09 global financial crisis the UK’s state spending as a share of our GDP shot up from around 40 per cent to 46 per cent, the highest since the 1970s.

Meanwhile, the share of UK economic output taken in tax dipped from 37 per cent of GDP to 36 per cent.

This is because the financial crisis sent the UK into its deepest recession since the 1930s. The then Labour government, in order to support the economy, kept its spending constant and cut some taxes, even as the economy contracted by 6 per cent.

But it was the collapse in UK GDP in the crisis, rather than changes to tax and spending policies, that explains the big moves shown.

A record deficit

As the gap between spending and tax revenues rose, so did the UK’s deficit. Total state borrowing in 2009-2010 peaked at £158bn, a post-war record.

This level of borrowing was cited by the new Conservative chancellor, George Osborne, as a justification for his radical programme of tax rises and spending cuts known as austerity.

The deficit has descended

As a share of GDP the deficit peaked at around 10 per cent in 2009-10. As a result of the austerity programme it had descended to 1.8 per cent of GDP in 2018-19.

This is even lower than it was going into the financial crisis, when public borrowing was around 3 per cent of GDP. But the deficit will be projected to rise over the coming years in Wednesday’s Budget, although by how much is uncertain.

But debt carried on rising

The deficit is annual additional borrowing. This means that as long as a government is running a deficit its nominal stock of debt is rising.

Even as the deficit was coming down, the UK government debt stock as a share of GDP rose, hitting a peak of 83 per cent in 2017-18.

It has, however, come down slightly since then, standing at 81 per cent of GDP in 2018-19. Yet it remains well above the 34 per cent of GDP going into the financial crisis.

And we will find out on Wednesday whether the debt as a share of GDP is expected to fall or not over this parliament, something Conservatives have long argued is important for the fundamental stability of the public finances.

Health dominates public services spending

This year the government is spending £132bn on health and social care.

This kind of expenditure has been rising in recent years as the profile of the population has been ageing. The next biggest outlay for public services is education (£64bn) and defence (£30bn).

But austerity has had a massive impact on public services

Under austerity, health spending and the aid budget (administered by the Department for International Development) were protected in inflation-adjusted terms.

But almost every other Whitehall department has suffered deep cuts in day-to-day spending budgets.

The hardest hit has been the local government department, which has had a real terms cut of 77 per cent per capita.

Other government departments that have seen huge cuts have been the transport and business departments, which have both seen the budgets essentially halved over the past decade.

The chancellor is expected to announce big increases in infrastructure and capital investment spending in Wednesday’s Budget, but it remains to be seen by how much individual departments’ day-to-day public service spending budgets will rise – and how much of the public sector austerity of the past decade will be reversed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks