Economic View: This 'lost decade' is not Europe's first

It is time to stand back. We have had a few days of deep disruption in both Greece and Spain, and for anyone who knows and respects both countries the sight of people rioting in the streets is profoundly troubling. Economic policy has to work with the grain of society: no government in a democracy can impose policies that are not seen, by a sizable majority of the population, to be both necessary and fair. Try and you might get sullen acquiescence for a while, but you will also get, at best, economic stagnation with all the corrosive effect that has on society.

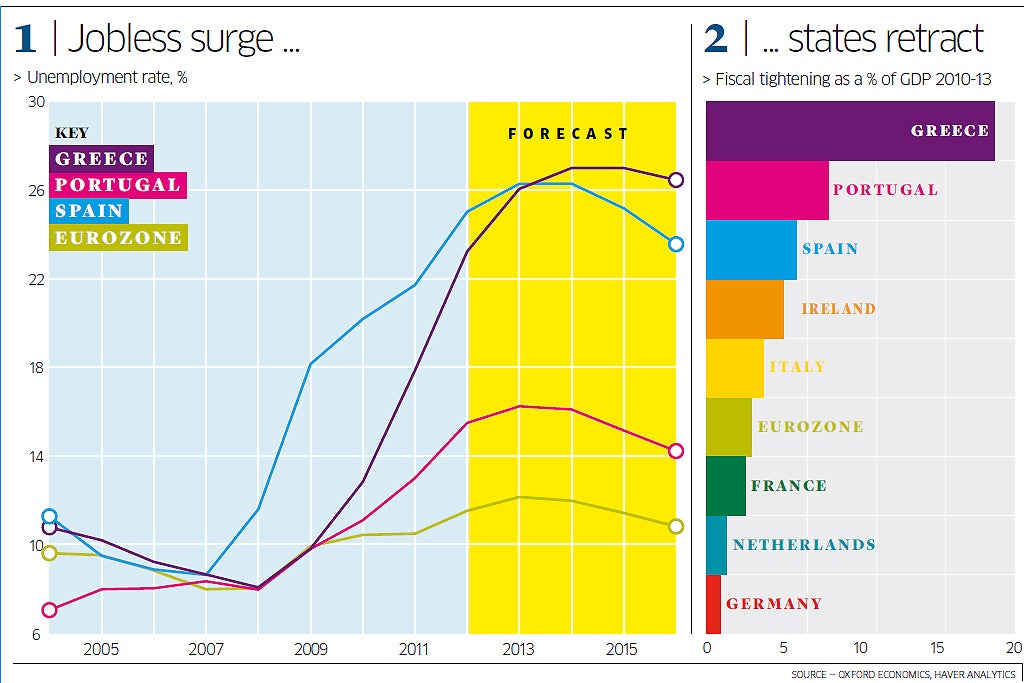

This sense of despair across much of southern Europe is caught in the new forecasts from Ernst & Young for the eurozone economies, from which the graphs here are taken. As you can see, the surge in unemployment that has taken place shows only modest signs of receding two or three years away. The authors of the report write in terms of a "lost decade" for Europe – not what it said on the can when the single currency was sold to the people.

You can also see the scale of the squeeze on fiscal policy – the amount by which governments have chosen, or been forced, to tighten policy over the three-year period to 2013. Everyone is tightening but the weakest are tightening the most. We are seeing the results in the streets.

That much we can observe. How we filter the mass of information coming out of Europe depends on our mental model. Some people focus on the economic projections, looking at when growth might resume, the scale of wage cuts needed to make the fringe countries competitive again, and so on.

Others look at the money: how much debt has Greece accumulated, the interest on that debt, and how it might be repaid, or rather not repaid. But if you look to economic history to seek parallels there seem to me to be two that sort of fit the story.

One is the break-up of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange-rate system, which ran from the end of the Second World War through to 1972. Those of us who were taught our economics in the 1960s will recall that while there was a huge amount of work done on the weaknesses of the system, there was no real acceptance that it might come to an end. The alternative of floating exchange rates was seen as a recipe for chaos, which in a way proved to be the case in the 1970s. However, despite the flaws in the fixed exchange-rate system, it took several years to die. If you take as a starting point the sterling devaluation in 1967, it was about five years.

The other parallel is more relevant to the events of the past few days. It is Britain's "winter of discontent" of 1978-79. The protests and disruption continued through the 1980s but it took the experiences of that winter to convince a majority of the population that we could not go on like this. We had already had the experience of Edward Heath's three-day week (the joke in the German newspapers was that "now you British can only strike for three days a week") and the IMF bailout of 1976. But before that winter there was not the critical mass in the country to demand change.

No parallel is a perfect fit. In the run-up to the UK's IMF bailout there was a lot of hostility to the world's banking community – the "gnomes of Zurich" – but not to Europe as such. In the three bailouts so far, of Greece, Portugal and Ireland, hostility has been focused on the bankers, as you might expect, but also on the European authorities and, in Greece particularly, on Germany.

Some of us think that it is monstrously unfair to single out the one country that has followed its own advice and scrunched down costs and consumption to make itself competitive. It is also unwise, since German taxpayers are, one way or another, underwriting the whole eurozone project. When Spain gets its formal bailout, presumably very soon, it will be interesting to see how the blame is distributed.

Apply these two parallels to what is happening now, and what might this tell us about the future? The first thing to be said is that we are not yet at any sort of turning point. As far as the Bretton Woods experience is concerned we are still in the 1960s. We can see the weaknesses of the design but the majority view is both that these can be fixed and that the consequences of a break-up are so serious that they don't really bear thinking about. Some of us disagree with that and think the costs of keeping the system going are almost certainly greater than the costs of change, but that is not a majority view.

As far as winter of discontent parallel is concerned, I think most of southern Europe is still very much where we were in the mid-1970s. Of course, the situation varies from country to country, with things more advanced in Greece than in Spain, still more so than in Italy. But even in Greece the professional elite, now dubbed technocrats, is still in control. No one can hope to predict the event or events that will crystallise change. Nor can we see to what extent change in one country will feed into another. Street protests can carry on for a while and there may need to be some external event to transform protest into policy action.

My own guess is that sullen acceptance will be the norm for some time yet – maybe years. So the notion of a lost decade may prove right. But it is not a lost decade for northern and eastern Europe. The German boom is slowing but there is the prospect of sustained growth. Sweden has got its public debt down below 40 per cent of GDP and is running a surplus. Parts of eastern Europe are managing an astounding recovery: Estonia has become the fastest-growing European economy.

So, we should not be too gloomy about the future of Europe as a whole, notwithstanding the protests in parts of it now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks