John Vincent: Chewing the fat with the King of Leon

Fast food, fast mouth, but the school dinners tsar and entrepreneur talks sense

Teachers of Great Britain, David Cameron's school dinners tsar has a message for you: Michael Gove is a good guy really.

As I tuck into my breakfast (smoked salmon and avocado) at Leon, the healthy fast-food chain that John Vincent runs with fellow kids' canteen adviser Henry Dimbleby, he tells me this: "People think he only wants to focus on getting children to learn Latin, in Greek, with teachers wearing mortar boards and gowns. But they've got him all wrong."

Really?

"Really!"

And here begins one of many lively, opinionated monologues from this excitable entrepreneur. "Look, I know Michael Gove is not the most loved person by some newspapers, but he genuinely believes education is the best way out of poverty. When he came into office, he deliberately over-emphasised the academic subjects. Because he felt like a turnaround CEO when it came to discipline and the academics."

That's me told.

Publicity-wise, at Leon, Mr Vincent is somewhat overshadowed by his business partner, presumably due to the journalistic fame of Mr Dimbleby's father. But it's fair to say Mr Vincent is equally charismatic (and, dare I say, better looking, with a Hugh Grant eye-wrinkler smile and a tall, casually clad frame).

Married to the journalist and newsreader Katie Derham, with whom he has two daughters, he talks a lot about his Doctor Who-loving family and has clearly built his business ethos around them and their Friday evening meals together.

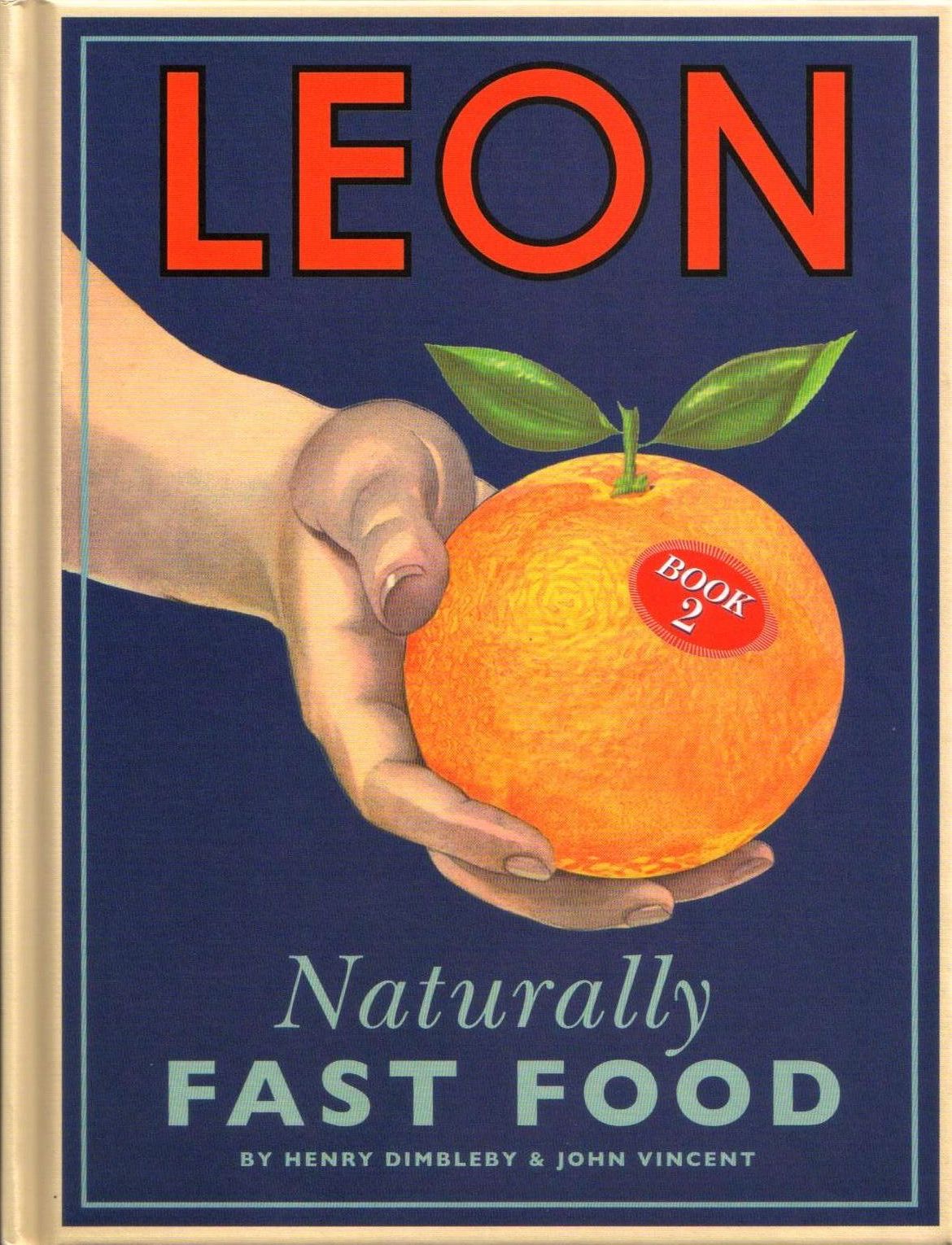

The Leon chain is named after Mr Vincent's father. It's growing rapidly in the South- East, with plans to double in size this year through an additional 12 sites, including Heathrow. Its cookbooks were one of the Christmas hits, spreading the healthy-food concept across the country.

Born and raised in Enfield, north London, Mr Vincent, 42, went to a primary school where "most of the lads had ear-rings and a lot were the kids of local gangsters." Secondary education was posher (though the dinners still weren't great): Haberdashers' Aske's private school. Despite that, he talks in a London twang, unlike the Old Etonian Mr Dimbleby.

He describes his poker and horseracing-loving father as being very moral, and his mother Marion, a teacher, as "the most positive person I've ever met". Although he put his dad's name above the door of the restaurants, he says both parents formed his outlook on business. The moral thing is easy to see in a Body Shop-type enterprise that plays heavily on the health agenda. But the positivity ethos sounds, frankly, wishy washy. I ask him to elaborate.

He cites his and Mr Dimbleby's recent year advising the Government on school dinners. This was, he says, framed around finding the positive aspects of current practice and building on it, rather than lacerating the way it's done now and coming up with radical alternatives that the Government kicks into the long grass.

The approach resulted in a report in which nearly all the parties involved were "on-side" and key measures were already being enacted by the time it was published. One recommendation – free primary school meals for all – became the most memorable line at the Lib Dem conference.

Along with that positivity comes faith in his staff and a hope that they will be "responsive" when they see things going wrong in the business. What does he mean by that?

He slaps a garish packet of Marks & Spencer "Percy Pig and Pals" fruit juice gums down on the table: "This!" he booms. "This is a company, M&S, which in many respects does some very moral things. And here is one of their biggest-selling products, sold in their impulse aisle. Now, I'm guessing by the fact it's called Percy Pig and Pals, and it's got some farmyard cartoony animals on it, that they are not afraid of selling these to children," he grins. "I'm also guessing that when they say 'soft gums made with fruit juice', they expect you to believe it's made of fruit juice. But let's see…"

He flips the pack over to the ingredients panel. Glucose syrup, sugar and, after a long hunt," 'juice concentrate… 3 per cent!' Not only is it only 3 per cent but it's concentrate, which is basically sugar. It might as well say 'sugar, sugar and sugar'."

He picks up the pack and throws it down again. Bad pig.

But it isn't just Percy he's cross about. Nor is it that M&S markets the stuff in the way it does. It was the staff having no idea how to respond when he complained to the checkout woman. "All I got was, 'I don't know – it's not my job to question it'."

It is emblematic of why so many people hate big business these days, he says.

"I grew up in the 1980s when business and entrepreneurialism was seen as being a fun and positive thing. Branson, the godfather of entrepreneurs, totally showed how you could combine excitement and commerce.

"But during the 1980s and 1990s the Harvard Business School construct became prevalent. That assumed that, as a CEO, all you have to worry about is the share price. You can be totally amoral, because the share price reflects what you are doing to all the other stakeholders. It is the gauge for how happy with your business are your customers, society and suppliers.

"That is fine in theory but complete bollocks in reality. It might work if, instantly, a society could immediately understand the impact of a new nuclear or chemical plant being put up in their neighbourhood. Or if, instantly, suppliers could tell the long- term intentions of the company, or if employees were not fearful about speaking up. But none of those things are true. That Harvard Business School model is broken because the assumptions made in it don't stand up to reality."

Not only that, he says, but: "I sense a feeling among some business people that if you make money as quickly as possible, you can get a nice yacht and escape what you've created. People at the top of companies are far away from the communities they impact on."

Little wonder, he says, that business has such a tough time in the court of public opinion. People don't trust it because they don't feel they are listened to or respected by it.

He's right. As he is on most of the dozens of topics we cover in his 100mph delivery. But, as a dad of two from a family of teachers, I'm still not convinced about Mr Gove.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks