What is the Private Finance Initiative? And do Labour's plans to take it back 'in-house' make any sense?

What are PFIs? Have they really been a scandal? Is Labour's pledge financially feasible? And would it be desirable?

The shadow Chancellor John McDonnell has said a future Labour government would end the “scandal” of the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), review all contracts and bring such schemes “back in-house” if necessary.

But what are PFIs? Have they really been a scandal? Is this pledge financially feasible? And would it be desirable?

What are PFIs?

In a nutshell, they are a means of the state financing the construction of new public infrastructure – whether that is schools, hospitals, prisons, rail lines, or public buildings - without the Government having to raise the money itself up-front.

The traditional way for the Government to build a new hospital, for example, is to raise the money in taxes, or borrow it from the bond markets, and then pay builders to deliver the project. After that the public sector owns the asset.

But under PFI the Government commissions the builder to deliver a project using its own money, normally borrowed from the bond market. The state then pays the builder (or a separate company that buys out the contract) regularly to effectively lease the building or piece of infrastructure over several decades.

Who came up with this idea?

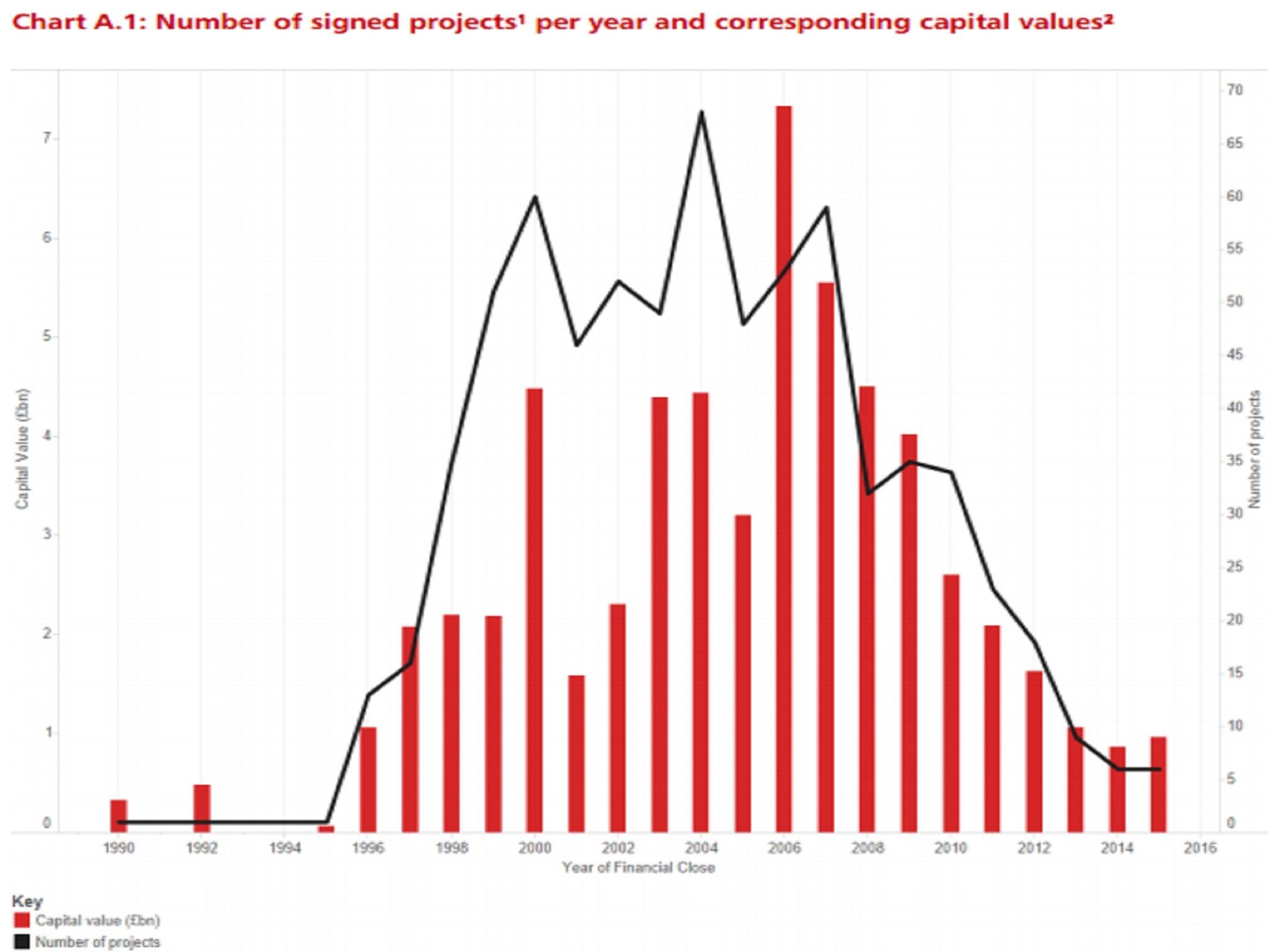

The first PFI was launched by the Conservatives in 1992.

But use of the financing schemes exploded under the previous Labour government.

At the turn of the millennium there were more than 60 new projects being signed-off every year.

But the number has fallen back sharply since then. There were less than 10 in 2015.

According to the latest Treasury data there are 716 projects (of which 686 are operational) with a capital value of just under £60bn.

Of this total the Department of Health was responsible for £13bn, the Ministry of Defence £9.5bn and the Department of Education £8.6bn.

What’s the point of it?

The justification used when PFI was being extensively rolled out was that the private sector would prove more efficient at delivering and managing projects than civil servants.

It was also claimed that such projects meant the financial risk of a construction project over-running was “shared” between the public and private sectors.

Could PFIs bankrupt the country?

Unlikely. Many fixate on the total value of all the re-payments due, which amounts to around £200bn.

But this is not a particularly useful way of estimating their financial burden on the state.

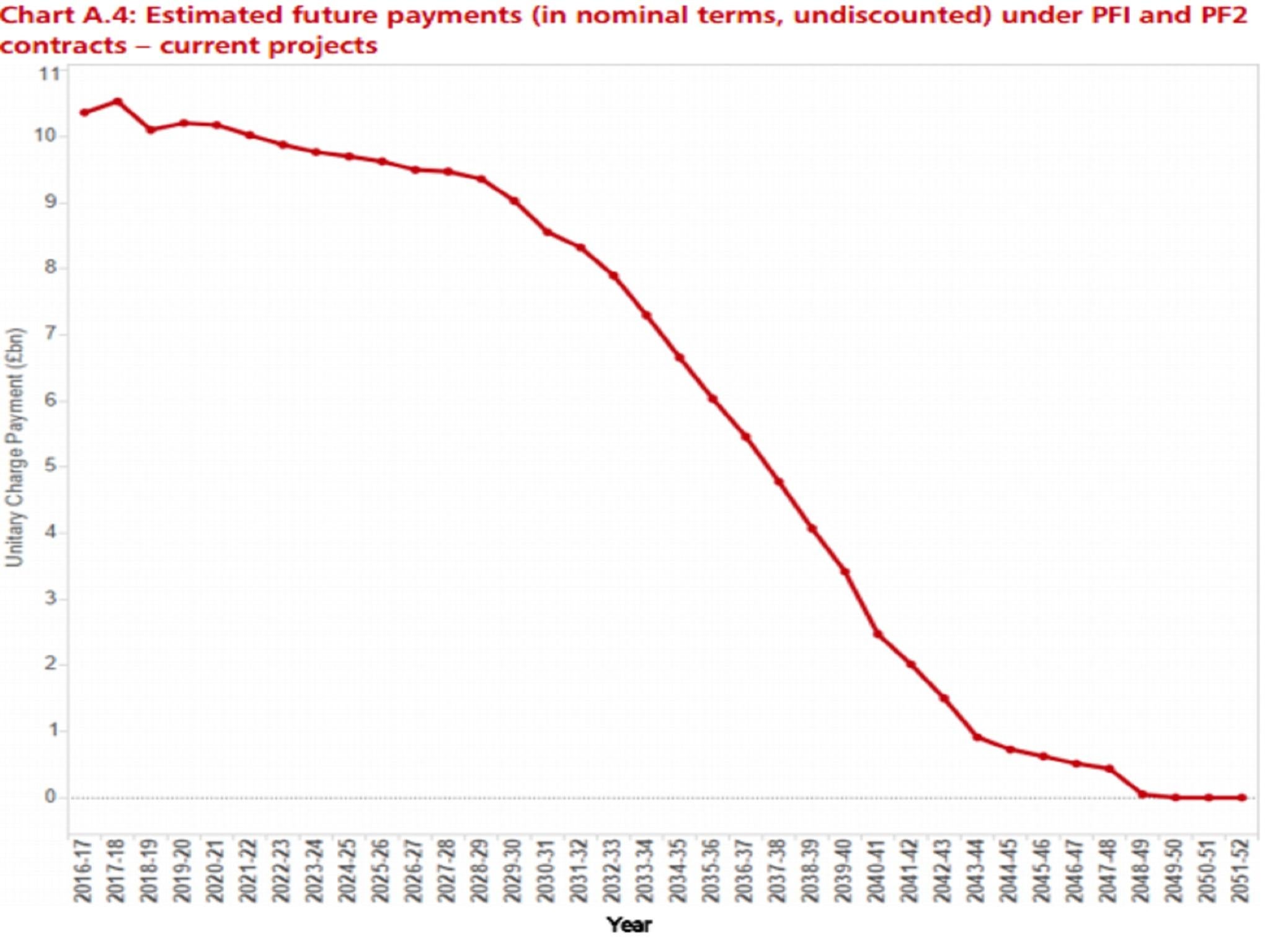

For that we need to look at annual payments. The value of all payments to PFI contractors is currently around £10bn a year, which is around 0.5 per cent of GDP.

This is hardly negligible, but it’s perfectly manageable for a Government that currently raises around £740bn in taxes.

Moreover, this outlay is expected to glide down to around £9bn a year by the end of the next decade. Thereafter such payments are projected to drop steadily to zero by 2050.

But aren’t PFIs poor value for public money?

This is a more coherent charge. It's clear that PFI is a more expensive route than direct financing. But the issue lies in whether projects are run more efficiently than they would otherwise have been, justifying the premium.

In 2011 the National Audit Office said there was insufficient data to reach a conclusion on value for money. But the NAO also noted Whitehall departments had not been making systemic evaluations.

There are also many accounting and public finance experts who are extremely sceptical of the value of PFI. Parliament’s Treasury committee reported in 2011 that it had “not seen any convincing evidence that savings and efficiencies during the lifetime of PFI projects offset the significantly higher cost of finance”.

It's often claimed - with some plausibility - that the former Chancellor Gordon Brown wanted to finance new public infrastructure but without adding to the official value of government debt, making PFI a kind of accounting trick for political presentation purposes.

Could PFIs easily be bought back ‘in-house’?

Some contracts are likely to have large exit charges.

A Labour spokesperson today suggested that contract holders could be offered government bonds in compensation.

But it's easy to see this prompting legal challenges.

But is it even a good idea?

Given the fact, as discussed above, that current PFI projects do not represent a major drain on the Government’s available resources this is questionable as a policy goal.

This is especially the case given the potential legal difficulties over scrapping long-term contracts.

As with Labour's proposed nationalisations, the issue is not so much the up-front expense or its impact on the official level of the public debt (additional public debt would be matched with additional public assets) but the question of whether these assets are likely to be run any more efficiently in the hands of the public sector.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks