Can millennials save Playboy?

The Hefners are gone, and so is the magazine’s short-lived ban on nudity – as well as virtually anyone on the staff over 35

“This is a full nude shoot to be conducted underwater,” a woman says into a phone, her voice carrying across a row of cubicles.

“Right, that’s right,” she continues. The person on the other end doesn't seem to quite get it. “As in, it won’t be on land.”

It was a Tuesday morning at the Westwood headquarters of Playboy Enterprises, and editors are preparing to close their summer issue. Gathered between a velvet love seat and a view of Santa Monica, they discuss upcoming stories – a piece on BDSM, a profile of Pete Buttigieg – while in the kitchen, a barista stencils bunny ears into latte foam.

In his office, Shane Singh, Playboy’s executive editor, explains that the underwater photo shoot, to be photographed that weekend, is for the magazine’s cover – but not in the way that older, leering readers might expect.

“The water is meant to represent gender and sexual fluidity,” Singh says, seated beneath a 1988 Herb Ritts portrait of Cindy Crawford. The women who will pose in that water – their limbs wrapped around one another in a ballet-like pose – are not simply models but activists. One uses performance art and digital media to share stories about the HIV epidemic. Another is an underwater dancer who promotes ocean conservation. The third, a Belgian artist, recently filmed herself walking naked through a Hasidic neighbourhood of Brooklyn during a sacred holiday. An angry mob chased her out.

“When they called me for this shoot, I thought there must be some kind of mistake,” Ed Freeman, the fine art photographer who created the cover image, later tells me. “I hadn’t paid attention to Playboy for many years, since I was a kid. And I thought: ‘Wait, they’re hiring me to shoot the cover? Do they know I’m gay?’”

This is a newer, woke-er, more inclusive Playboy – if you believe what company executives tell you, and if you are inclined to give an ageing brand yet another chance at reinvention.

Even before the #MeToo movement, there had long been debate over whether a publication with the tag line “Entertainment for men” had any place in an equitable world. But when Playboy’s founder, Hugh Hefner, died in 2017, that argument grew louder. Had Hefner been a forward-thinking voice for sexual liberation and free speech or a creepy old lecher who fostered a culture of misogyny?

At the time, Playboy was in a dizzying sequence of revival attempts. In recent years, the company has cut the magazine’s circulation, reduced its frequency, stopped printing ads, replaced chief executives and, most notably, briefly banned nudity – before bringing it back, with the tag line “Naked is normal”.

Early last year, Ben Kohn, a financier who had helped take Playboy private in 2011 and is now chief executive, told The Wall Street Journal that he was considering getting rid of the magazine to focus on licensing and joint ventures. But instead, Playboy was quietly relaunched this year – this time as a thick-stock, matte-paper, ad-free quarterly. It is edited by a millennial triumvirate: the openly gay Singh, 31; Erica Loewy, 26, the creative director; and Anna Wilson, 29, who oversees photography and multimedia. There had been women in the latter two positions before, but never both at the same time.

The result is a magazine that is virtually unrecognizable from the one Hefner created – and, for the first time in Playboy’s history, with no Hefners involved. Not Hugh, of course, nor his daughter, Christie, who was chairwoman and chief executive from 1988 through 2008, nor his son Cooper, who stepped down as chief creative officer in April. He said he would start his own adult content portal, HefPost. A Playboy spokeswoman says the Hefner family no longer had a financial stake in the company.

The summer issue, out now, features an interview with Tarana Burke, the activist who founded the MeToo movement, conducted by Dream Hampton, whose documentary about R Kelly led to multiple charges against the singer. There is a queer cartoon and a feature on gender-neutral sex toys. The fall issue will feature a photo feature by artist Marilyn Minter celebrating female pubic hair.

“We have red hair, blonde hair, black hair – it’s basically every colour of the rainbow,” says Liz Suman, 35, the magazine’s arts editor. She adds that elsewhere in the publication, “I’ve been sneaking in some penises, too.”

“Stuff like that wouldn’t have happened a year ago, for sure,” she says. “Or maybe it would have – but it wouldn’t have been celebrated in the same way.”

The ‘Big Bunny’ gets grounded

During its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, Playboy represented, to a certain breed of male consumer, a lifestyle: lavish, aspirational, sexually adventurous. Reaching nearly seven million subscribers at its peak, the magazine published the work of Andy Warhol, Margaret Atwood and Hunter S Thompson, as well as interviews with Rev Martin Luther King Jr and Fidel Castro. Soon there were clubs and resorts and casinos, as well as a Big Bunny jet with a discothèque inside.

But then came more explicit national magazines like Penthouse and Hustler, video pornography that made those magazines seem tame, and the internet, which derailed both paid smut and print publishing by making it all free.

Hefner sold the jet, and executives experimented with ways to enliven the brand, including an E! reality show, The Girls Next Door, which followed the exploits of a pyjama-clad Hefner and his multiple live-in girlfriends. One of the women, Holly Madison, later wrote a book in which she described Hefner as emotionally manipulative and said the women were expected to have group sex.

But the company was losing money. It sold its TV and digital operations to an internet porn outfit, and in 2011, Hefner secured financing to take the company private.

“I was there for sort of the last gasp, the last hurrah,” says Jimmy Jellinek, a former Maxim editor who served as Playboy’s chief content officer from 2009 to 2015. “We always believed in what I called ‘death with dignity.’ We never saw any way out of the spiral that we were in – no amount of reinvention, of taking out the nudity, of making it more interesting to millennials. So we decided let’s be as good as we can be, in the context of what we are.”

While the magazine withered, certain aspects of the Playboy brand remained viable business lines. Kohn, the chief executive, refers to it as the “world of Playboy”: branded spirits, furniture and perfume, fashion collaborations, a casino in London, pop-up events, a recently reopened nightclub in New York and more – especially in China. There, the brand has more than 3,000 stores selling suits, leather goods, luggage and outdoor clothing, Kohn said.

Playboy no longer publishes its financial results, but Kohn says consumers spend some $3bn on the company’s products and services each year. Relaunching the magazine, he says, made sense as a kind of “brand extension.” He likened the future of the company to Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop.

What’s the ‘Playboy Gaze’?

This newer, socially conscious version of Playboy has meant some changes to the vernacular that has long defined it.

Bunnies – the restaurant servers who work in the Playboy Clubs – are now “brand ambassadors.” Playmates – the women who appear as nude centrefolds – are no longer Miss September, for example, but the September Playmate. (There are three in each quarterly edition.) They are paid as freelancers and often continue to represent Playboy at public events; the company said it was working to provide them with health care benefits.

In the office, members of the staff use terms like “intersectionality,” “sex positivity,” “privileging” and “lived experience” to describe their editorial vision – and tout their feminist credentials. Two editors are former employees of Ms., the magazine co-founded by Gloria Steinem.

The photography looks different, too. Playmates – who no longer appear on the cover – are primarily shot by other women, with artsy angles and intimacy coordinators on the set.

“Something we always say to each other is that we create with intention,” says Loewy, the creative director, her desk covered with mock-ups for an upcoming shoot. Loewy is in a red dress and gold hoop earrings, a tiny jewel adhered to one of her front teeth.

“We think about everybody on set,” she continues, “from the PAs to the caterers to the makeup artists. Nothing is not considered in the creation of what we make.”

When Ryan Pfluger, who recently shot Time’s cover of Buttigieg, was hired to photograph actor Ezra Miller, he was told to “shoot Ezra Miller – but make it queer,” he says. Miller ended up choosing to appear in high heels and bunny ears. For the issue on stands now, Loewy reached out to Spanish artist Carlota Guerrero, the creative director for Solange Knowles. Guerrero pitched the idea of defying Barcelona’s topless ban by marching a group of seminude women, including transgender women and prostitutes draped in red fabric and red body paint, through the city’s red-light district.

On “a street that is predominantly owned by men and where every girl has a story of fear to tell”, Guerrero wrote on Instagram, “it was a statement for us to take that space back.”

“We talk a lot about what’s the Playboy gaze and how we need to diversify that,” says Rachel Webber, 37, the chief marketing officer. She joined the company last year from National Geographic in part, she says, because of the opportunity to bring a “heritage” brand into the modern era. “It’s who is behind the camera as much as in front of it.”

“It’s a little like being in a gender studies class,” she adds.

Using sex to sell

It all seems genuine enough. Except for the elephant in the room – which is that Playboy is still a magazine full of nude women, whose chief executive is a straight white male, with a discredited man still listed at the top of the masthead as the founding editor-in-chief.

“Through today’s lens, Hugh Hefner is grotesque and his women victims,” says Joanna Coles, a former editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan, when asked if it was possible to reinvent the brand. “They should lay it to rest with Hugh’s smoking jacket.”

Contradiction, though, has always been part of Playboy’s ethos – or what newer employees might call its “brand architecture”. Staff members today proudly recite that in 1955, just two years after Playboy’s debut, Hefner risked backlash to publish "The Crooked Man", a short story about an alternate reality where homosexuality is the norm and heterosexuals are persecuted.

At another point, the famed rallying cry “Gay is good” first appeared in a headline in the magazine. Playboy was an early backer of abortion rights and donated money to the Equal Rights Amendment campaign, civil rights causes and free speech organisations.

“At Playboy’s height of influence in the 1960s and early 1970s, it was what we might consider the 1960s version of ‘woke,’” says Carrie Pitzulo, a historian at Colorado State University and the author of Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics of Playboy. “The criticism that it objectifies women, that it privileges white heterosexual men is all true. But there is this other side of Playboy that hasn’t really been widely acknowledged.”

While some aspects of the brand’s history have been burnished over time, others remain a stain. Steinem’s 1963 exposé of working conditions at the New York Playboy Club is still a scathing read – and relevant in the face of recent criticism of the revamped club, where corseted female workers dress as “bunnies” and are instructed to “dip” when serving drinks.

And then, of course, there’s the Playboy mansion, with its famous koi pond, exotic zoo animals and hot tubs stocked with Johnson’s Baby Oil. It was sold in 2016 to J Daren Metropoulos, an heir to the Hostess fortune, but not without a plenitude of ugly stories – and a bacteria build-up in the famous grotto pools that caused an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease.

“Playboy wouldn’t exist if women and men were equal in our society,” Steinem told The New York Times last year. “It’s the gendered version of a minstrel show.”

‘The era of fuzzy dice and mud flaps is over’

Playboy’s circulation was last independently measured in December 2017 at just under 400,000, and according to Kohn the magazine now reaches “a couple hundred thousand” subscribers. The audience is three-quarters male.

Since Kohn took over two and a half years ago, he says, he has pulled back about $15m in partnerships and licensing deals for products he believes “no longer represent the brand.” He adds that the company was working to expand into cannabis, skin care, sex toys and sexual wellness.

“A phrase you’ll hear a lot around here is that the era of fuzzy dice and mud flaps is over,” says Webber, the chief marketing officer, pausing over a slice of avocado toast to explain what a mud flap is.

Since January, Webber had been working with her team to write a mission statement that reflects the company’s new direction. The goal, she says, is ultimately to reach an audience that is 50 per cent female. But she’s also realistic about the challenge ahead.

“Look, I think the target audience is ‘Let’s be relevant,’” she says. “But I do think that to be relevant, we’ve got to take a stand on things and appeal equally across all genders.”

According to a memo to partners about Playboy’s new “brand vibe”, that means being “intimate” but not “explicit,” and “cheeky” but not “cheesy”.

“We talk a lot about when something is objectification versus when it is consensual objectification versus when it is art,” Singh says. “I think objectification removes the agency of the subject. Consensual objectification is the idea of someone feeling good about themselves and wanting someone to look at them. Art means, OK, we can hang this on a wall. And if it’s both, for us, that’s the major win.”

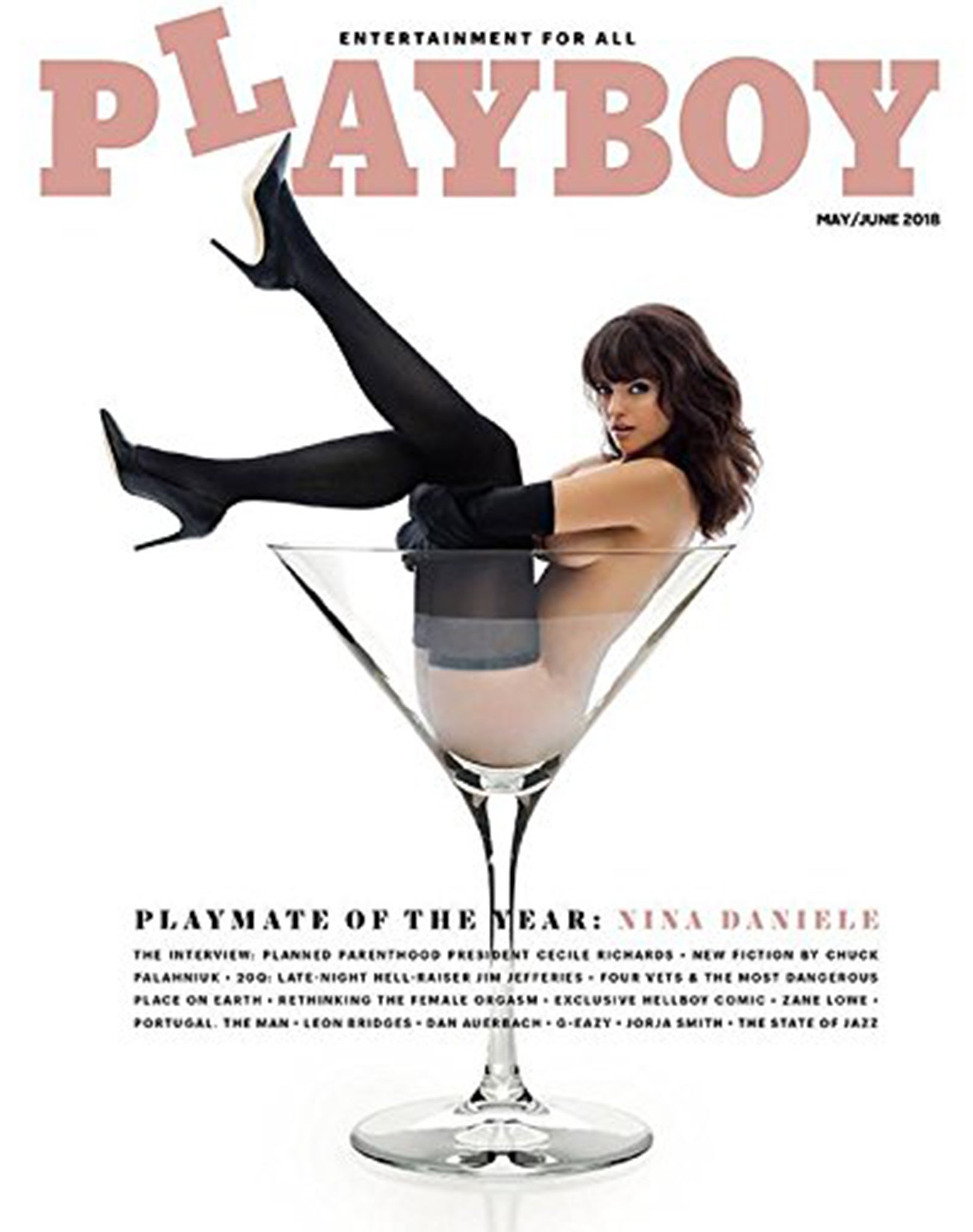

I ask him to show me the difference, and he shuffles through a stack of Playboy archives. There is one magazine, from around this time last year, whose cover featured a woman in thigh-high black stockings and heels, her butt resting in the curve of a human-size martini glass.

Singh laughs. “Do I need to explain why putting a woman in a martini glass is probably not something that we would do?”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks