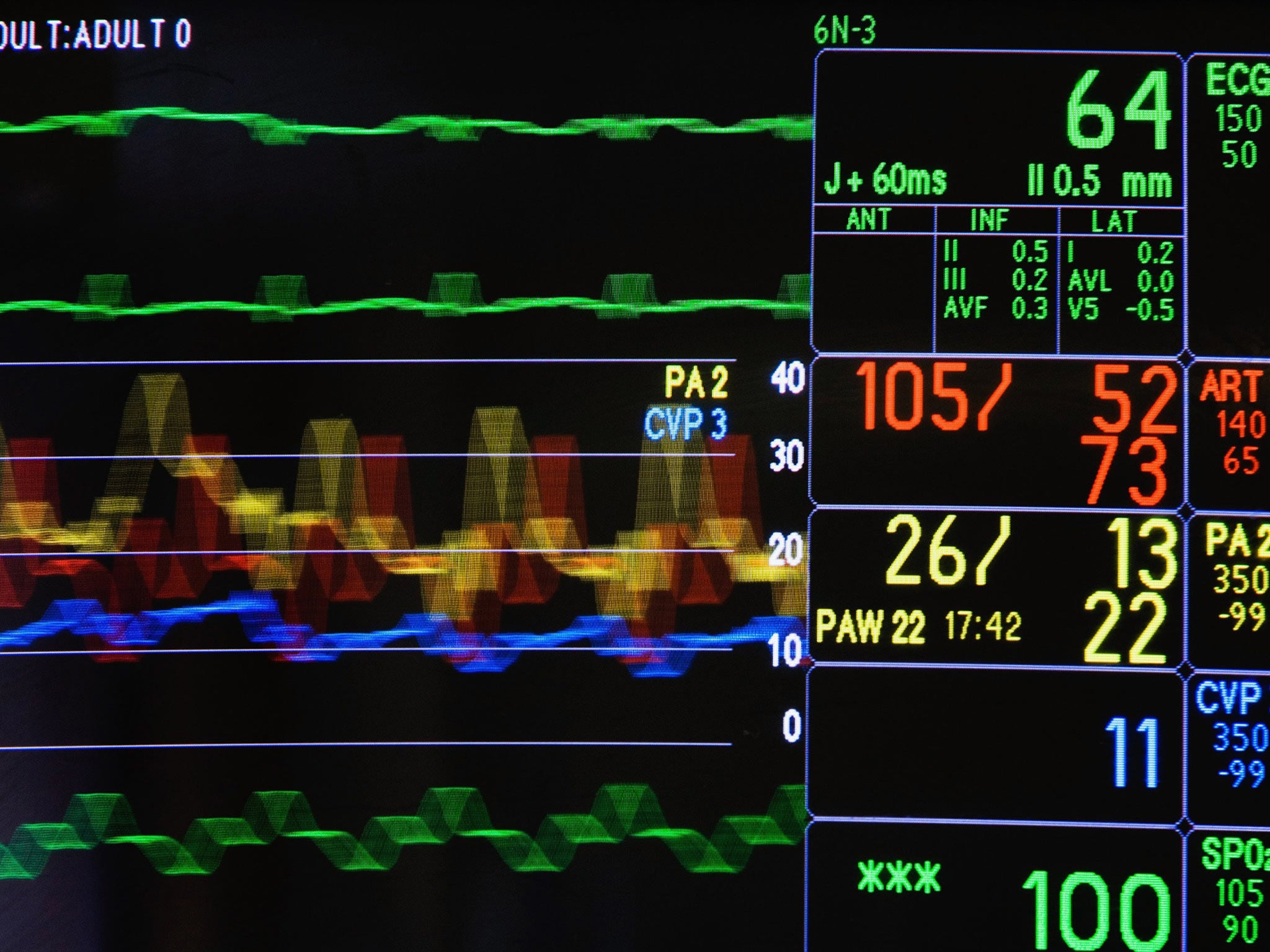

Emergency treatment continues but the global economy is still on life-support

No one believes China is growing at 6 to 7%. Official growth does not reconcile with underlying statistics

Mr Economy has spent much of the past seven years in an induced coma, with only a modest recovery from the Great Recession. The root causes of the life threatening 2008-09 episode remain unaddressed. Debt levels are higher now. Global imbalances remain. The financialisation virus has proved resistant to available medicines. Structural changes have proved difficult.

Growth, a vital sign, remains below trend. The IMF has slashed global growth forecasts four times in the past year. A medical board inquiry to investigate its fitness to forecast has commenced.

Trade growth, another key indicator, is weak. In recent history, trade growth has averaged double economic growth rates. But now trade growth is below economic growth rates, suggesting there are further falls in activity to come.

Disinflation or deflation remains a concern. Normally, stable or falling prices would not be problematic. However, Mr Economy’s high debt levels would become unmanageable under such conditions.

Efforts to boost inflation have failed. With oil prices around $40 a barrel, sharply lower commodity prices and over-capacity in many industries, the chances of improvement are low. Low or negative interest rates, in part engineered to bring down Mr Economy’s elevated debt levels, signal that higher inflation is unlikely.

Mr Economy’s various parts are performing unevenly.

US growth, at about 2 per cent, remains below par. Producing things which end up in inventory does not seem viable in the long run. America’s improvement was driven by a lower dollar, growth in emerging markets and a revitalised energy sector, which is now reversing.

The expectation was that in 2015 America would be able to come off its low-interest-rate medication. This remains the plan. But higher rates may curtail progress. Investment, already slow, may fall. A stronger dollar, already up more than 20 per cent, will affect corporate profits and export competitiveness. It may trigger financial market instability.

Europe and Japan are in more desperate condition. Europe’s tentative recovery was driven by negative short-term rates, massive QE, a weaker euro (driven in part by these policies) and low oil prices. But the continent has a deteriorating outlook, with economists hunting with microscopes for second decimal places of improvement.

German exports to emerging markets are slowing. The Volkswagen emissions scandal has brought into question Europe’s much-vaunted technical prowess. Debt problems remain unresolved. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris, the French government has announced that it will not abide by deficit and debt limits. Italy refuses to bring its public finances under control, despite a worsening debt-to-GDP ratio.

Greece is likely to be in spotlight, with a relapse probable. Portugal’s new government, an uneasy coalition between foes, has sworn allegiance to the EU and the euro but is seeking major concessions. With the highest total debt-to-GDP in the EU, a Portuguese debt restructuring, explicit or de facto, is not unimaginable.

Despite positive talk, Spain’s public finances remain poor and its unemployment unsustainably high.

Europe’s refugee crisis may actually boost economic activity but will be expensive, at about €10,000 (£7,500) per refugee per year initially, pressuring weak finances. It has also highlighted deep divisions within the EU and a rancorous decision making process.

Questions about the EU and euro continue. Finland is in recession, unable to respond by adjusting its currency or interest rates. The Finnish parliament is to hold “Fixit” hearings next year, debating an exit from monetary union and a return to the markka. At some stage Britain will vote in a referendum about its possible Brexit.

Japan has entered its fifth technical recession in seven years, casting doubts on the ability of Abenomics to jolt it out of two decades of economic stagnation.

No one believes China is really growing at 6 to 7 per cent. Official growth does not reconcile with underlying individual statistics such as trade, investment, consumption and real production. It is incompatible with policy actions, which include six interest rate cuts since November 2014, steps to increase bank lending and devaluation of the renminbi.

With China contributing between a third and half of global growth, a deceleration will set off negative feedback loops in the global economy. Other countries are reliant on China as a source of demand, with about 40 countries having it as their largest export destination.

Like China, once a bright beacon of hope for Mr Economy, emerging markets face several headwinds. Sub-par growth in developed markets and China, combined with low commodity prices, are key sources of weakness. Deep seated structural problems, including inadequate infrastructure, lack of institutions, corruption and environmental degradation, are now impinging on activity.

Mr Economy remains on life support. He is stable but the prognosis is uncertain.

Satyajit Das is a former banker and author whose latest book, ‘A Banquet of Consequences’, is published internationally this month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks