Hamish McRae: Whisper it quietly – but there are chinks of light in Europe's darkest hour

Economic View: Reform fatigue is mounting as visible results in growth and jobs fail to materialise

Europe may be experiencing a "darkest hour before dawn" moment. Quite aside from the results of any easing of fiscal policies among the eurozone member states, there are signs of a spontaneous upswing just taking hold. The backward-looking data are terrible; the forecasts for this year for Italy and Spain bad almost beyond belief. Yet there are forward-looking indicators that, under the circumstances, are not too bad.

You always have to be careful about calling turning points, and this one is no exception. The OECD's greatest single concern for the eurozone is, quite rightly, its unemployment levels, which look like reaching 12.2 per cent this month. But that is just one measure of a wider malaise. As the OECD's chief economist Pier Carlo Padoan said yesterday: "Protracted weakness could evolve into stagnation, with negative implications for the global economy. Reform fatigue is mounting as visible results in growth and jobs fail to materialise."

Those negative implications extend particularly to the UK, which looks like being the best-performing large European economy this year – or perhaps one should say, given the OECD's rather dismal tally, the least-badly performing one. But, and this is the good news, you can pick up more positive signs for Europe in the forward-looking data, some of which are shown in the graphs.

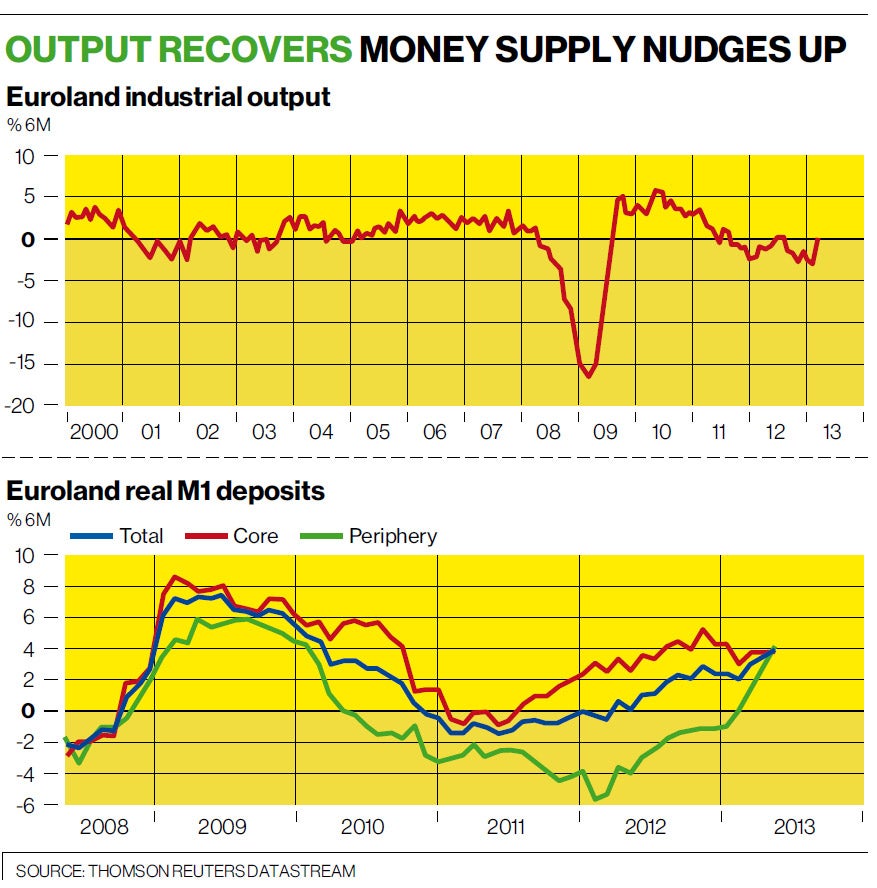

On the top is industrial production. As you can see, there was a strong rebound from the catastrophe of 2008-09, but this petered out and for the past 18 months or so industrial output has been falling. But now, just in the last month or so, that fall seems to have come to an end. It is not yet in positive territory but just stopping the decline is progress.

Now look at the bottom graph. This shows money supply in both the core and periphery of the eurozone. It was positive right through last year in the core, as you might expect, but since the beginning of the year it has also turned up in the fringe.

Simon Ward of Henderson Global Investors, who highlighted this in a new post, notes that the core-periphery distinction is becoming less relevant. The recovery of the fringe is being led by Italy but Spain is also looking up a little; only Portugal is still contracting.

Does money supply matter? Well, the link between money supply and economic activity is not a clear one, and there is a question as to which measure of money you should take. It sounds a bit black-boxy, but this particular measure, narrow money, does give an early feeling for what is happening in the real economy.

If you think about it, if the amount of money in current accounts or other cash deposits is rising, some of that additional money might be spent – or at least has become available for spending.

It does not really matter which way round the relationship works. It may be because money supply is going up that people feel more able to spend, or it may be that because economic activity is rising that firms need to increase their cash deposits.

All we need to know is that there is some sort of association between narrow money supply and economic activity – and as you can see, the numbers do look quite encouraging.

So where does Europe go from here? The easing of the pace of fiscal consolidation in Europe must make sense. We hear a lot in Britain about our own pace of consolidation but it is nothing as to what is happening in Europe.

Of course, nothing changes in the long run and some countries, notably Italy, will have not just to balance the budget but also to run large surpluses for a generation are they not to default.

But if an economy has contracted for six or seven straight quarters, there is not a lot of point loading on yet more taxes. You should tighten fiscal policy in the boom years, not the slump ones.

On the wider question of the survival of the eurozone, there is no doubt that the various measures by the European Central Bank to ease policy have bought time.

The present calm in the markets, with for example the 10-year yield on Italian debt down to just over 4 per cent and on French debt to just over 2 per cent, is a symbol of success.

Those of us who were sceptical of the effectiveness of the ECB policies have, for the time being at least, been proved wrong.

It may well turn out that the eurozone authorities can pull the currency through this downturn with its membership intact, something that did not look likely a year ago. But the cost has been huge in both economic and human terms, and will continue to be so.

In any case, my own instinct has always been that the great crisis for the eurozone will come during the next global downturn, not this one. We can have little idea when that will be, except to observe that, given the sequence of global recessions, you would expect another downturn around 2017.

That does not give long for countries to get their debts under control. Some, including the UK, look like going into the next slowdown while still running a deficit.

It might seem a bit premature to start writing about the next slowdown when we have barely emerged from this one. Those growth forecasts for the eurozone this year are profoundly depressing. This was not at all what it said on the can when the euro was proudly launched.

The probability remains that continental Europe will remain a generally depressed region for a decade, maybe longer. But there is slight sense of a pick-up in activity, even in Italy and Spain, and that deserves to be recognised and nurtured.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks