A slowing Chinese economy could be good news for Western consumers

Economic View

The global recovery has been disappointing but you can, to some extent, explain this poor performance away. Recoveries from recessions associated with financial disruption have always been slower than those brought about by other factors. But in the past few days we have had to contemplate something even more disturbing: the possibility that below-par economic growth will continue for the foreseeable future. The proposition is that there will continue to be growth, but it will over the cycle be weaker than it has been for most of the past 50 years. It will be difficult for the next generation, at least in the developed world, to be richer than its parents.

This concern has been around for some months but a couple of events this week have brought it into sharper focus. One is the new set of growth forecasts from the International Monetary Fund; the other, the slowdown in China, where growth is now the slowest it has been since 2009.

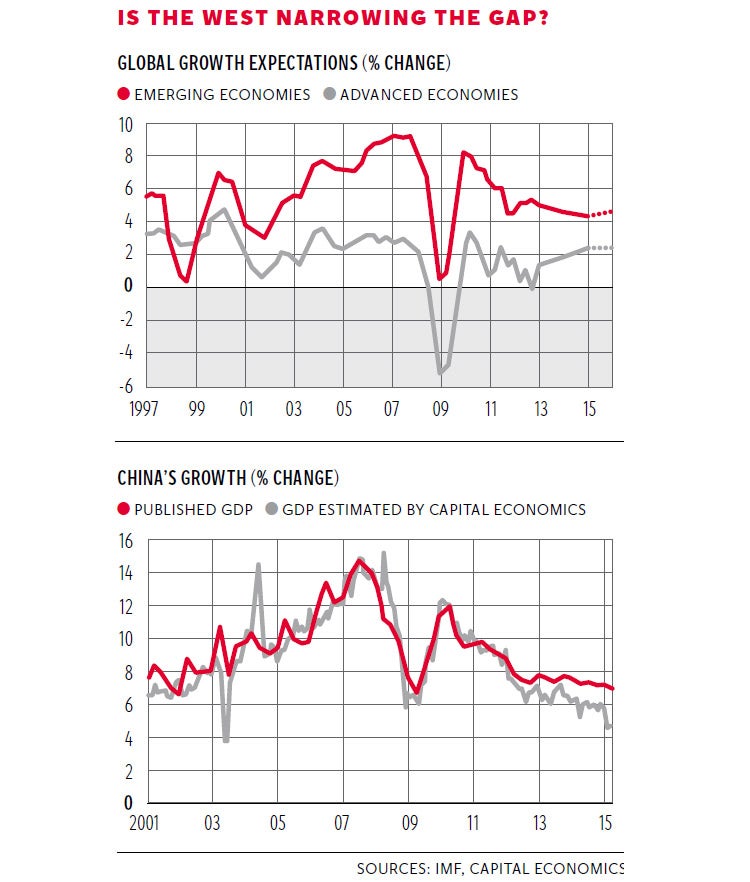

The IMF forecasts are a good place to start thinking about the long-term outlook, though they only run forward a couple of years. The big picture here, as you can see from the top chart, is that there is a continuing but weak recovery in growth in the developed world, countered by a slight slowing of growth in emerging economies. The latter is still projected to grow faster: at 4.7 per cent next year against 2.4 per cent, but the gap is narrowing. However the 2.4 per cent for the developed world is not great, given that there is still a large output gap. When you consider that there has been a huge new stimulus from the halving of the oil price and quantitative easing by the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank, alongside near zero interest rates, you would expect that gap to be closing fast. But aside from the US, UK and some smaller economies, it is barely doing so at all.

Mario Draghi, president of the ECB said he saw “clear evidence” that QE was working, and it is true that – Greece apart – most of the eurozone is moving forward. But if the IMF is right and growth this year is 1.5 per cent and 1.6 per cent next, that is not enough. At best that would be trend growth and self-evidently you need above-trend growth to close an output gap.

This perception that the world economy is doing worse than it ought to be doing has been picked up by a number of economists. For example Stephen King, chief economist at HSBC, feels that we don’t recognise the extent to which the world has changed and that our economic models do not pick up these structural changes. As a result, they have been persistently over-optimistic. A more specific point has been the way the cut in the oil price has given the boost you might have expected because of the emphasis on renewables. Last year, for the first time ever, more additional electricity generating capacity installed in the world came from renewables rather than fossil fuels.

As far as the developed world is concerned it does now seem clear that we have reached the limits of what monetary policies are likely to achieve. John Llewellyn, the London-based economic consultant, noted in a paper that while we were at the end of the road as far as conventional policy was concerned, there were other things that could be done to boost demand. Among them would be the splitting of governments’ capital and current accounts, so that they can use this period of very low interest rates to finance infrastructure projects without appearing to be fiscally irresponsible.

But while there are some shots in the locker, it is hard to see the developed world as a whole achieving significantly faster growth. Whether you call that “secular stagnation”, the fashionable expression of the moment, is open. My own view is that the wounds of the developed world are largely self-inflicted and there is enough growth around to be reasonably confident that the output gap in the US and UK will be closed within the next three years. But viewed overall, most growth will come from the emerging world and here, the big story is what is happening to China.

It looks very much as though this year and next India will grow faster than China. Longer term that will surely be the case, partly because India has more potential catch up before it is in danger of entering the middle-income trap and partly because of different demography. India will pass China in total population in about 10 years’ time. Right now, however, the hot issue is the slowdown.

It is always difficult to know quite what is happening. The official figures are that GDP growth in the first quarter was 7 per cent, but it may be a lot slower than that. Capital Economics looks at things such as electricity output (which is negative) and builds an alternative indicator which, as you can see from the bottom graph, shows that growth may be close to 5 per cent a year. Even this may be too optimistic. Some estimates by Diana Choyleva, head of research at Lombard Street Research suggest China’s real GDP actually fell by 0.2 per cent quarter on quarter. Worse, she thinks real domestic demand plunged by 2.1 per cent, which would be the worst since their data series began at 2004.

We will see. I think the main point here is that it would be normal and natural for growth in China to slow as its population ages and its living standards rise. Even at these lower rates, it is still adding more demand to the world economy than the US. In any case, slower growth brings other benefits in that it will, other things being equal, reduce demand for energy and raw materials.

This will help the developed world, because lower prices mean we, the consumers, get more for our money. That helps in the short term. In the long term, there is no evidence that the developed world has become less ingenious or less inventive. As long as that is the case there is no reason to expect secular stagnation – even if it is hard to see quite where growth will come from.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks