At last, some good news: working seems to add to our well-being

Economic View

We may be getting richer, albeit slowly, but are we getting any happier? The function of economic activity is to create goods and services that meet people’s needs and desires, but we all know that the main way in which we measure activity, gross national product, is a crude and partial one. It just happens to be better than anything else. But given its inadequacies, the work of the Office for National Statistics to look at other measures, in particular well-being, deserves a welcome. Its latest such report, Life in the UK: 2016, was out on Wednesday.

The core message is that on balance things are getting better. The ONS takes 43 measures, which range from whether people feel safe walking home after dark, to how we feel about our family life. There are objective measures, such as life expectancy, and subjective ones such as satisfaction with life in general. As you might expect, questions about health show improvement, but there are glitches. For example there seems to have been some increase in the prevalence of anxiety or depression, albeit a small one, and people seem less satisfied by amount of leisure time they have.

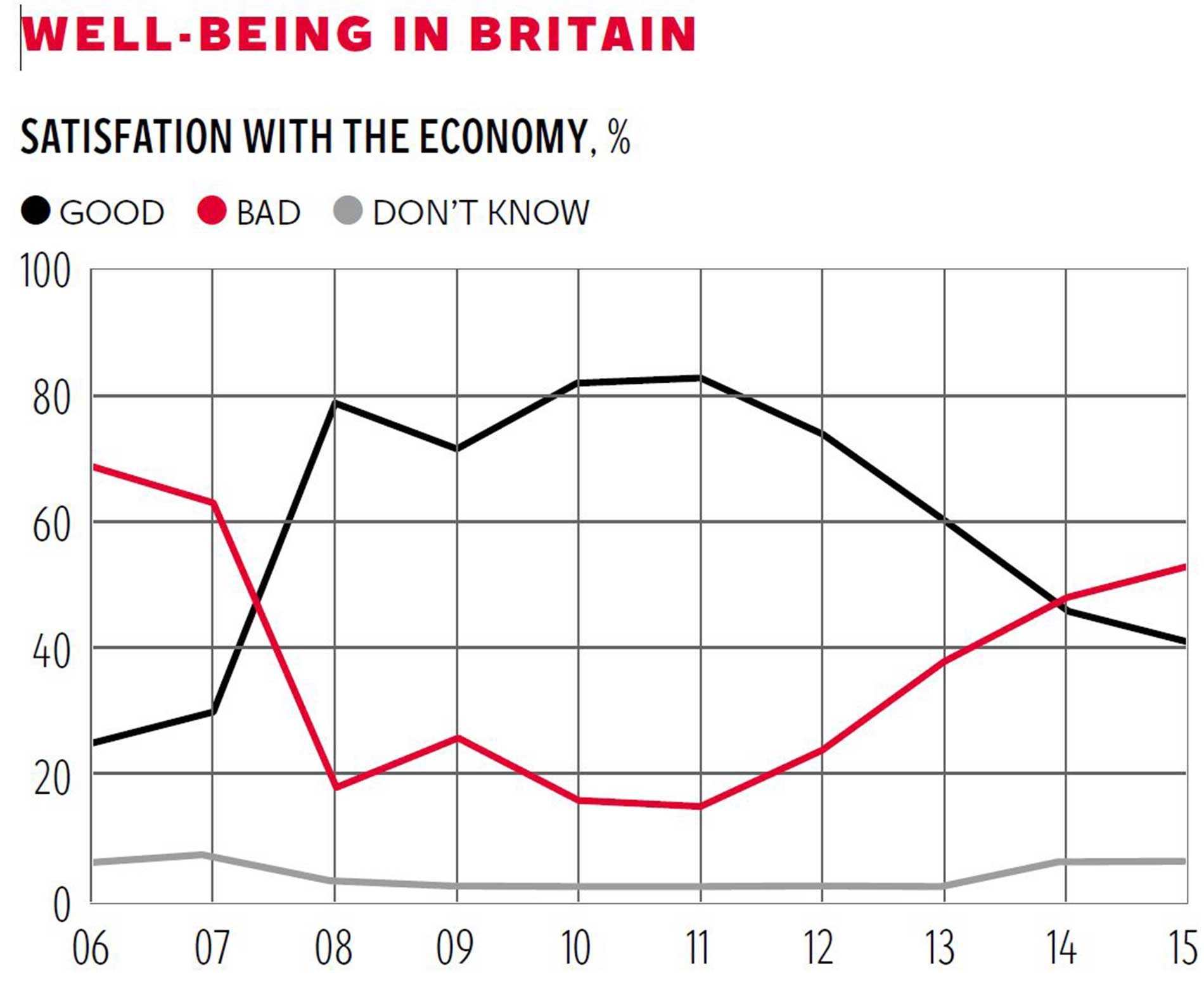

There is such a huge amount of data that it is hard to know which bits to pick out, but two are highlighted in the charts here. The top one shows perceptions of the state of the economy. As you can see, while people are not so chipper as they were before the great recession, they have come some way back towards the levels of 2006. At least more people now are generally satisfied than dissatisfied. That may be related to the fact that in 2015, real family incomes were at last past their previous peak. On that measure the 10-year squeeze on living standards has ended.

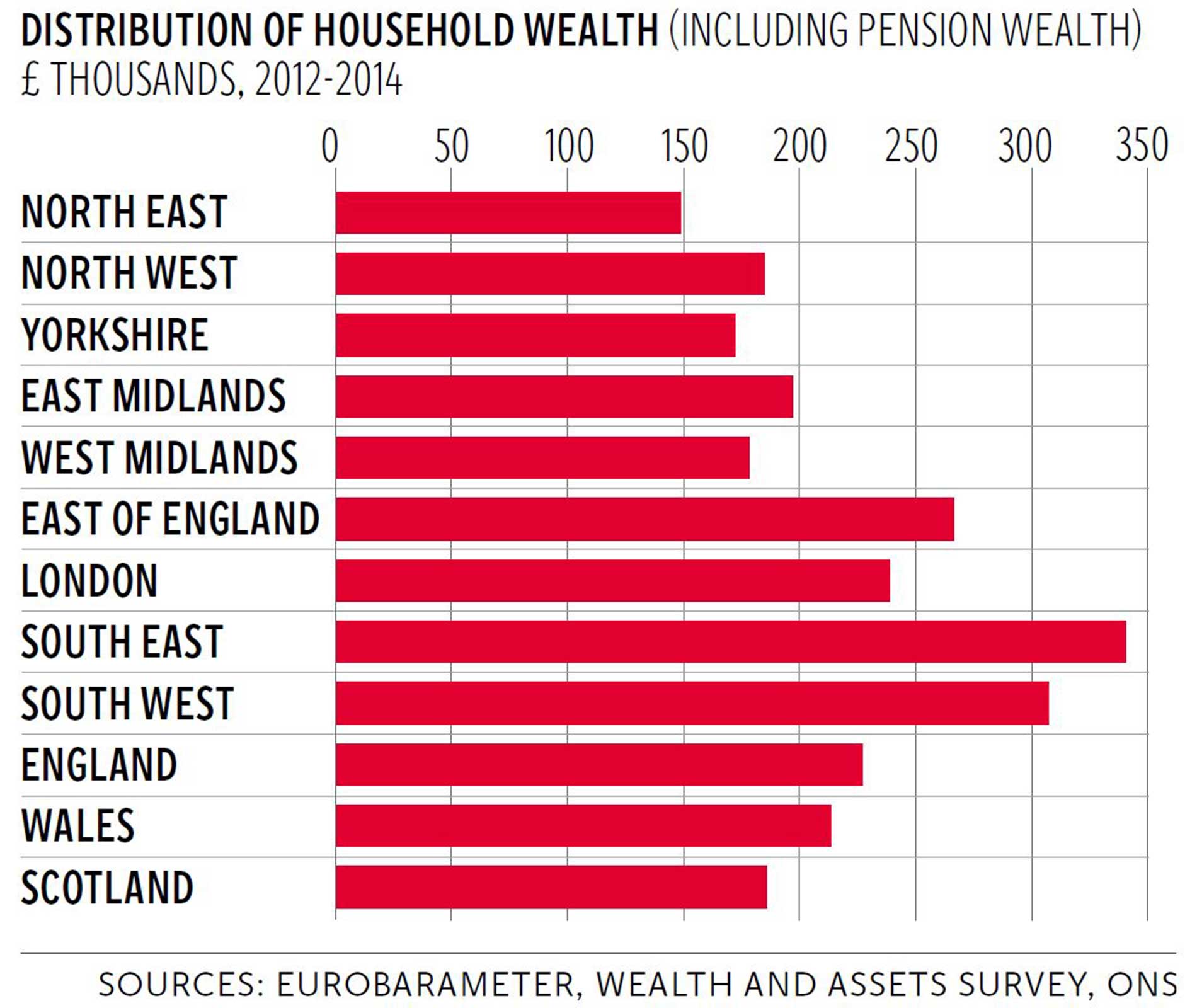

The bottom chart shows wealth: how much wealth the median family has in different parts of England, as well as in Scotland and Wales. The middle family in England is wealthier than the equivalent family in Scotland or Wales, with net wealth of some £230,000. The richest median family is in the South-east, with nearly £350,000, ahead, perhaps surprisingly, of London. The poorest family would be in the North-east. This divergence is partly a function of house prices, but also the size of mortgages, and hence the age of the homeowner. It also includes pension wealth, which again will skew results towards older people. The top 10 per cent of households have 45 per cent of the nation’s wealth, and to be in that top 10 per cent you need to have wealth of more than £1,048,500. The bottom 10 per cent, by contrast, have only £12,600 of wealth.

A number of other results stand out. One is that the better educated people are, the happier they are – or at least that is what they report. More than 80 per cent of people who have a university degree say they are satisfied or highly satisfied with their lives. That proportion falls to around 65 per cent for people with no education qualifications.

Another is that trust in government is higher than it was three years ago. It is still low: only 31 per cent of people say they tend to trust the government. This is however pretty much in line with trust levels of people in other European countries. Unsurprisingly people in Greece, Spain and Portugal trust their national governments even less than we do ours. More surprising, however, was that just before the election last year trust in government reached 37 per cent, the highest it had been since the series began in 2004. That may not seem high, but the coalition apparently ended up with higher trust levels than even the Blair/Brown governments managed to generate during the boom years.

One bright area is the environment. The UK is ahead of the target to produce 15 per cent of its energy from renewables by 2020, though we are doing less well on recycling. Only 45 per cent of household waste is recycled, against a target of 50 per cent, with Wales having the highest recycling rates and Scotland the lowest.

Another area where progress has been made is in cutting crime. In the year to March 2015 there was an average of 57 crimes against the person for every 1,000 adults. That was down from 82 crimes in the year to March 2012. On the other hand, while the proportion of women feeling safe walking home after dark has increased, the proportion of men feeling safe has remained the same.

Finally, there is a clue in the numbers which may explain why, despite a decade of squeezed incomes and despite the slow recovery, life satisfaction seems to be nudging upwards. It is that people who are in work report materially higher levels of satisfaction than those who are unemployed. That you would expect. But – and this is the point – people in work also seem to be more satisfied than those who choose to be economically inactive. If this is right, and I think we have to be careful in interpreting answers that people give about something so nebulous as “life satisfaction”, then a number of things become clearer.

One is that high labour participation rates, the highest now that they have ever been, may well be associated with general rising well-being. Another is that the rising number of people beyond normal retirement age who are still working may also be pushing up national well-being. And a third is that the rise of part-time working may be making people happier, too.

This is really encouraging. If people like working, the general financial and social pressures for people to do some sort of work, including volunteer work, will tend to make the country a happier place. Some people have seen the flexible labour market and the rise of part-time working and self-employment as a cause of insecurity, and that may be so. But overall if it gets more people into work then the chances are that it will improve well-being – and that, as noted above, ultimately matters more than GDP per head.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks