Central banks have handed out cheap money to investors for long enough

Economic View

These are difficult times for investors. The developed world economy is established in recovery mode, with even the eurozone experiencing a few months of reasonable growth. Employment is rising in the US and UK, which is good for consumption. And inflation remains low, which increases real earnings.

It sounds like a “Goldilocks economy”, not too hot, not too cold, a combination that you might think should be good for investors. But it hasn’t been. The FTSE 100 index is down by 6 per cent over the past two months, and global bonds have apparently had their worst quarter for 25 years. True, these declines are from record levels and you could see this as a healthy consolidation. But it is hard not to detect a whiff of fear. So what’s up?

Let’s get rid first of the lazy explanation: that the markets have been unsettled by the events in Greece. It has not helped, but suggestions that shares might fall by another 10 per cent were Greece to leave the euro seem over the top. Equities may fall by that amount or more, but for global shares to fall because of something going wrong in a country that is less than 0.4 per cent of the world economy is really not credible.

There are two other explanations and they are related. Both concern central banking policy. One is that the rise in global interest rates will turn out to be faster than investors have been led to expect. The other is that central banks are no longer willing to flood the world with liquidity, essentially to rescue investors. The key player as far as the first is concerned is the Federal Reserve; as far as the second, the European Central Bank.

A few months ago the markets expected the Fed to put up rates after its June meeting, the one that took place on Wednesday. Now it looks like September, though that will depend on the progress of the US economy. There is a natural temptation to try to go through the remarks of the Fed chair, Janet Yellen, with a fine-tooth comb, but in reality what happens to interest rates will be determined by what happens to the economy.

However, while you can have a debate as to whether there will be one rise in rates this year or two, what happens to long-term rates is really more important than what happens to short-term ones. Hardly anyone doubts that they will tend to climb over the next few years, but it is really difficult to have any feeling for how smooth or bumpy that ascent might be.

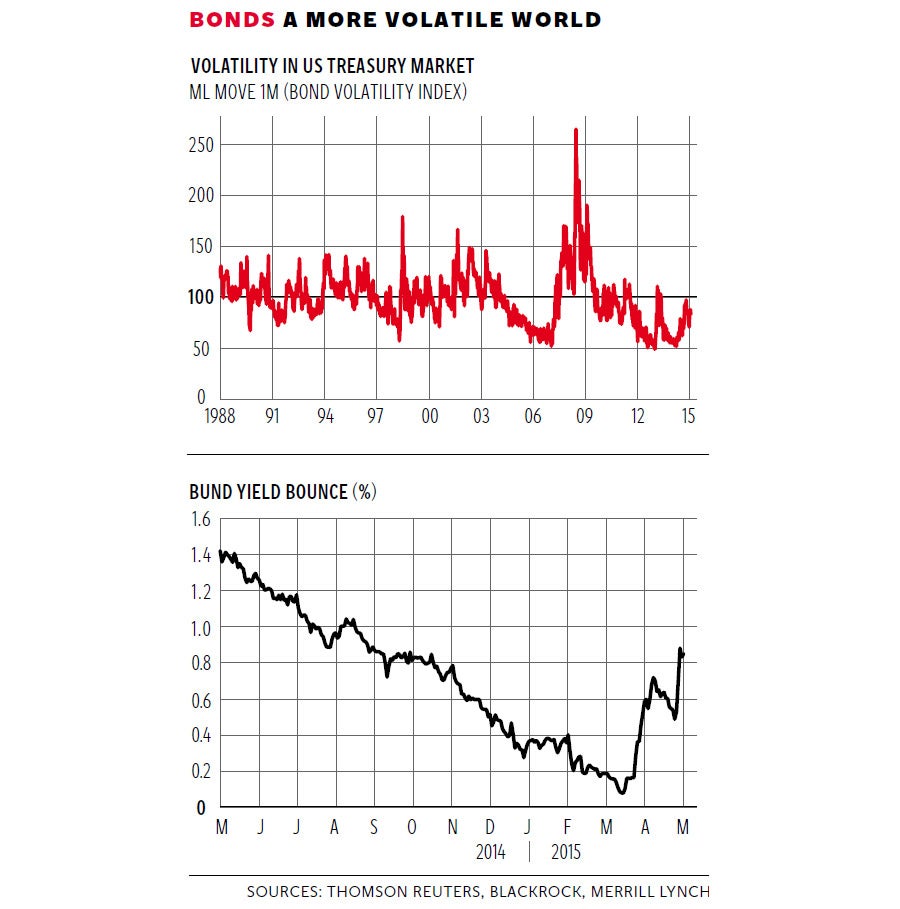

BlackRock, the huge fund management group, has just put out a paper noting the dilemmas facing investors, and the two charts here come from that. The top one shows volatility of US Treasury bonds – how much prices jump about – and the interesting thing here is how recent months have been reasonably stable by historical standards. Long-term yields are still very low. But while the 10-year Treasury yield was 2.35 per cent, that is nearly a full percentage point up from its level in July 2012, and the climb from there has by no means been straight line. The only sensible assumption is that it will be more bumpy in the future.

Bumpy markets create opportunities but they also create risk. There has been a tacit assumption among most professional investors that if things really go haywire, the central banks are there to pump liquidity into the system. That is what has happened since 2008. But at the ECB’s monthly press conference earlier this month, Mario Draghi, the president, voiced a warning: “One lesson is that we should get used to periods of higher volatility. At very low levels of interest rates, asset prices tend to show higher volatility.”

This rather put the cat among the pigeons but it is of course common sense. In any case, the bottom for German Bunds was reached on 17 April, and since then there has been a sharp rebound, as you can see from the bottom graph. Put the US experience and the German experience together and you can make a case that the 30-year bull market in bonds has ended and – who knows – that a 30-year bear market may have begun.

When you are faced with possible turning points the thing to look for is past experience: what do bear markets in bonds look like? The trouble is that there aren’t really any good precedents. We did have rising bond yields from the 1950s through to the early 1980s, but the conditions of the 1950s were so different from those of today that they don’t help much. Then there was a global savings shortage; now there is a global savings glut.

There is a narrower parallel between now and the bond market rout of 1994, when yields suddenly shot up. Holders of fixed-interest securities were highly leveraged then and when rates started to move up they had to sell to meet margin calls. The inevitable result was even greater falls. David Owen of Jefferies International has drawn attention to that in a recent paper. But again the parallel doesn’t work that well, because both interest rates and inflation were much higher then. We are seeing a flip in expectations now, from deflation to presumably mild inflation, and you could argue that unless inflation takes off, a very gentle climb in bond yields would be the rational response.

I struggle with this argument. Why hold bonds at all when they offer so little real return? Ten-year gilts are on 2 per cent, the same as the inflation target. So a buyer implicitly expects either the Bank of England to undershoot the target over the next 10 years, or that there should be zero real return on the investment. Anything must be better than that.

Nimble investors may be able to make money by nipping in and out of bonds, but for the long term at these yields they make no sense at all. The more this view takes hold, the more volatile the bond markets are likely to become.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments