Hamish McRae: Debt need not be obstacle to growth

Economic View

Can you combine private sector-driven growth with public sector-driven austerity? It is quite clear that we will have the latter at least for the rest of this decade, probably beyond it. This week we will get the Autumn Statement, with another update from the Office for Budget Responsibility about the slippage of the Government's deficit-reduction programme, and the Chancellor's response to that. The deficit is going up, not down, and the longer it takes to get back to balance the bigger the debts that will have to be serviced by future generations of taxpayers.

The question is whether this condemns us to slow growth. In emotional terms, can you have "animal spirits" in the private sector driving the economy forward, with a sense of depression in the public sector as budgets are ground down year after year?

It would be nice to point to precedents for this, but we have never had such large fiscal deficits in Britain (or the US) in peacetime so we have never had to face such a long period of fiscal consolidation. However there are examples elsewhere of countries having to cope with similar situations. These include Canada and much of Scandinavia in the early 1990s. One of the reasons why Canada came through the last crisis in such good shape was because it had made such a mess of things some 15 years earlier.

Canada is a special situation, with its energy resources and its close economic relationship with the US. Something like 90 per cent of its GDP, excluding energy, is generated within 100 miles of the US border. So perhaps the best example for us is Sweden, which in the early 1990s had to rescue its banking sector and get its public spending back under control. At its peak, public spending in Sweden reached 67 per cent of GDP and even the Swedes were not prepared to pay the level of taxation to fund it.

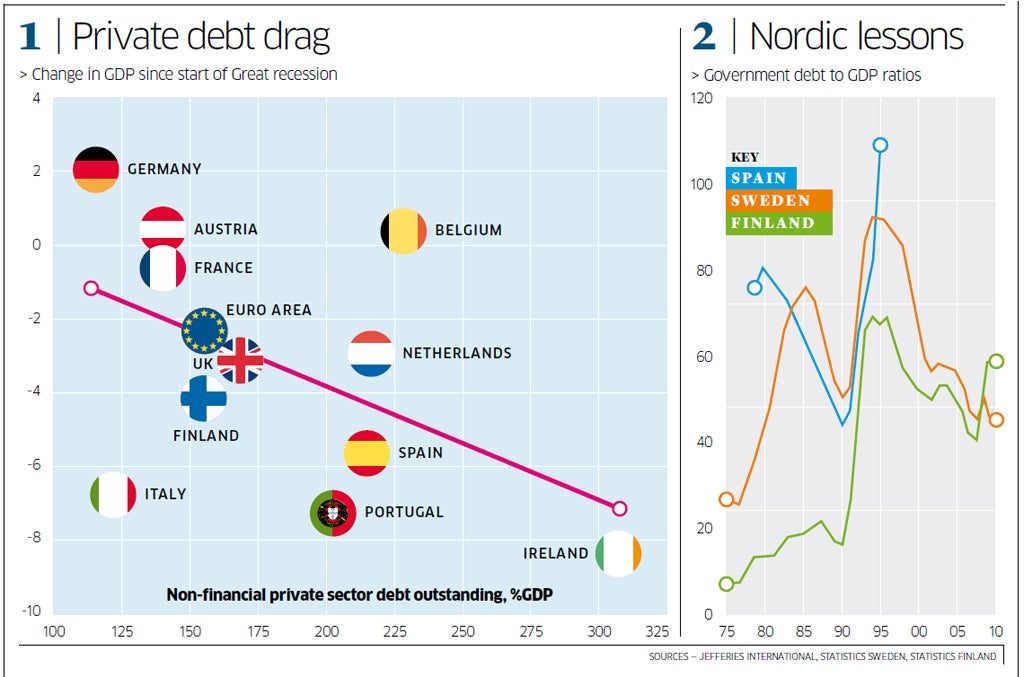

So what happened? There has been some good work on all this by Marchel Alexandrovich and David Owen of Jeffries International. Alexandrovich looks in particular at the lessons that Sweden and Finland have for Spain, concluding that the big difference now is that Spain cannot devalue to increase its competitiveness and reduce the real value of the debt. The surge in public debt that took place in the early 1990s for those two countries is quite similar; the problem is that Spanish debt is still rising whereas that of Sweden and Finland was, at the same stage of the cycle, starting to fall – as you can see from the right-hand graph.

We in Britain can devalue, and have indeed done so. But we are not getting much growth. So what are the lessons for us? Alexandrovich argues that from Scandinavian experience, a prerequisite for a return to growth is private sector deleveraging – until ordinary people and ordinary companies start cutting their debts the economy cannot return to growth – but they don't have to complete this paying-back for growth to begin.

This relationship between private debt and growth is explored by David Owen and you can see the results in the big graph. It appears that countries with very high private sector debts – Ireland being the extreme example – have suffered most seriously during the downturn, while those with relatively low debt, such as Germany and Austria, have done best.

What does Swedish experience tell us about what happens next? Well, by 1994/5, a couple of years after the crisis, the economy was growing strongly despite the fact that both the private sector and the public sector were paying back their debts quite quickly. Much the same happened in Finland. Ben Broadbent, the former Goldman Sachs economist now on the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee, notes the same phenomenon: that after a financial crisis, private sector debt carries on falling well after growth returns.

I suppose this is really common sense. Once bitten, twice shy. If you have had to struggle to meet the monthly mortgage payments, you use any spare cash to pay down debt when you have the chance. Any small company that has its overdraft squeezed down by its bank will want to build up a cash reserve. You can see this in the figures for equity withdrawal – people borrowing against the value of their homes. From the late 1990s though to 2007 Britons boosted their consumption by equity withdrawal. Since then we have been paying down mortgage debt.

There is however a long way to go. Net personal debt is still high by historical standards. British individuals have paid back perhaps a quarter of the excess debt generated in the boom years. So the great question is whether we collectively feel we have paid down enough to start spending again. That applies of course to individuals but also to smaller companies, where investment has been weak.

On the company investment side there really doesn't seem to be much happening. Whether that is because cash-rich companies feel they need to conserve their funds or whether it is because cash-weak ones cannot borrow is unknowable, but probably a bit of both. Maybe the new schemes to boost funds for business may help but evidence is thin.

On the other hand the consumer mood is not too bad. The latest consumer confidence figures rose sharply, albeit from a low level. Retail sales seem all right but let's wait for Christmas. Fortunately consumption is a much larger element of final demand than investment and presumably if consumption does continue to nudge up, investment will follow. So, yes we can have growth while the Government pays back its debts. But the "animal spirits" to drive the next boom are a long way off – mind you, that may be no bad thing.

Irish eyes could soon have a reason to start smiling again

Some slightly brighter news from Ireland. A brief trip there last week made me aware that, maybe, just maybe, the corner has been turned.

Those of us who visit Dublin regularly would say it feels buoyant in a way that it has not done since the end of the boom. But that is not Ireland – as a Trinity College Dublin economics student put it to me: “We live in the Dublin bubble”.

So you look for evidence. The most important bit is that the private sector is now creating jobs, some 20,000 in the past year. That may not sound a lot but it would be roughly equivalent to 300,000 in the UK.

The public sector is still cutting back so there has been a small net fall in employment but at least the relentless decline seems to have been stopped. Actually figures last week showed that unemployment fell marginally, though at 14.8 per cent it is still dreadful and long-term unemployment is still climbing.

The next bit of evidence is retail sales, with underlying volume up 1.3 per cent in October and up more than 3 per cent on the year. This is the best result for more than four years. Now try house prices. They fell a tiny bit last month but after some rises. It looks just possible that the bottom of the market was last June and Danske Markets thinks they could rise by 5 per cent over the next year.

To be set against all this is the downgrade in the OECD forecasts, which now suggest there will be barely any growth next year – unsurprising you might think given the flat performance across the eurozone and Ireland’s dependence on exports.

There is a budget gap this year of more than 8 per cent of GDP, and expectations are that the debt-to-GDP ratio will be 123 per cent next year, even worse than projected earlier this year.

So rationally there is little cause for cheer. But turning points matter because a sniff of a turn in one aspect of the economy (retail sales, house prices, whatever) reinforces the turn elsewhere. Ireland may be nearly there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks