Hamish McRae: Italians do the eurozone a favour by checking austerity

Economic View: The policies imposed on the weaker eurozone members have reached the limits of the politically possible

Beware warnings of earthquakes, at least of the political variety. There is a temptation to see the Italian electorate's rejection of austerity, which it was, as a catastrophe for the eurozone. It may eventually turn out that way, and I think the balance of probability is that Italy will eventually default on its debts, but in the immediate future it is possible that the Italian voters may have done the eurozone a good turn. They have checked austerity and they will trigger a monetary boost.

The argument goes like this: Governments have to balance their books over the long-term and the "technocratic" government of Mario Monti has made decent progress on that score. But the costs, not just in loss of economic output but in damaging the life prospects for a mass of young people, have been dreadful. Worse, the fiscal squeeze has not been accompanied by a corresponding squeeze on bureaucratic costs. Worse still, Italy has barely begun to make the structural changes, notably in the labour market, that will enable it to regain sustained growth.

It is easy to see why. It is always difficult to assault privilege, always hard to take something away. That is why it is much better to push through reforms in good times rather than bad, though unfortunately it is during bad times that the pressure mounts to take action. It is also better to to spread the burden of austerity as widely as possible, for example by devaluing the currency – which increases inflation and thereby hits all spenders – rather than piling the burden onto a narrow band of people, such as the young unemployed.

But by doing austerity without reform (or rather with only limited reform) and doing so without a democratic mandate (the Monti government was imposed) Italy has tested this particular approach to destruction. Something else must follow.

We cannot know what that will be. But what we do know is that the policies imposed on the weaker eurozone members have reached the limits of the politically possible. For example, it is not now conceivable that Ireland or Portugal will be required to tighten policy any more. The Irish economy, incidentally, seems to be picking up a little pace with unemployment falling sharply in the final quarter of last year, albeit to the dreadfully high level of 14.2 per cent. Spain? Well, it will stagger on with the partial bail-out of its banking system until it needs further financing, which it will get. As for Greece, it is simply not possible to impose any further austerity on the country.

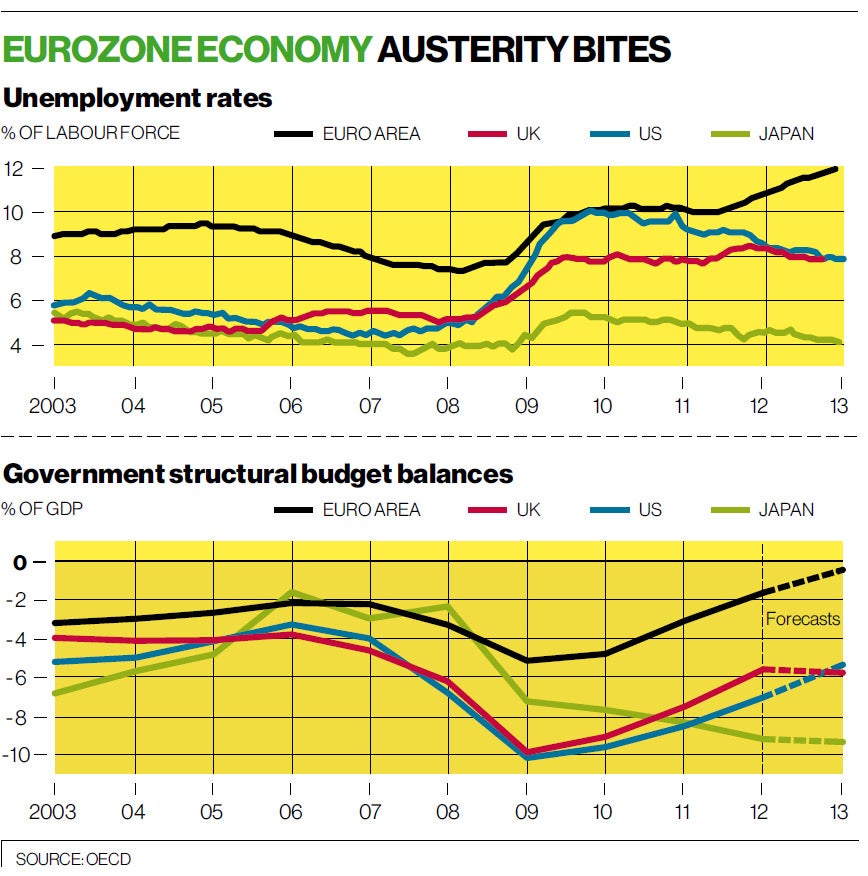

However, if we have reached the limits of one policy, it is worth noting that this is having an effect. If you look at the fiscal position of individual countries there are some concerns, but if you look at the eurozone as a whole, it is making a swifter correction to its previous mistakes than either the US or UK and vastly swifter than Japan. I have put in the graphs both the costs of austerity (in unemployment) and the progress towards a balanced budget – a structural balance; that is, a balance over the economic cycle, rather than an absolute one.

So you can see, as a grand generalisation, that eurozone finances are in better shape than ours. Yet of the large European economies, only Germany can borrow more cheaply than the UK. Italy borrowed for 10 years at just over 4.8 per cent, a rate that markets seemed to feel acceptable. But the yield on the equivalent UK debt fell close to 1.9 per cent, the lowest since early January, as investors began again to see gilts as a "safe haven". (There is a nice irony that long-term gilt yields are now lower than they were ahead of that ratings downgrade last Friday. Clearly what matters is not what the rating agencies say, what matters is what investors feel.)

So what will happen? I cannot guess at how Italian politics will develop but I can just see the weaker eurozone economies, Greece apart, managing to stabilise themselves enough over the next few months to avoid a eurozone break-up in the next three or four years. For example, eurozone economic sentiment is still low but is starting to climb a little, and while bank lending is weak, eurozone money supply is growing, a slightly different signal of better sentiment – though retail sentiment is still dire.

There is one further force that we will see deployed in the coming months: the European Central Bank not only finding further ways of easing credit but also directly buying sovereign debt. The mere threat to do the latter, provided countries were following sound economic policies, from the ECB president Mario Draghi did calm the markets for several months. The balance of probability now is the ECB will have to carry out that threat, though it is impossible to see the circumstances with any clarity. We have seen the limits to austerity but we have yet to see the limits of ECB monetary policy and that is where attention will now shift.

GDP revisions put paid to all that talk of a triple-dip

A quick word about those revised gross domestic product figures.

The headline contraction for the final quarter of last year was unrevised at 0.3 per cent, but revisions to earlier data show that the economy was not flat last year but grew a little, albeit by only 0.2 per cent. That is the total economy. If you knock off the impact of the decline in North Sea oil and gas and look at the onshore economy, it grew by 0.6 per cent. That is not great; in fact it is pretty terrible. But I expect further revisions to come through and show it grew by around 1 per cent last year, the common sense "feel" you get from looking at things like VAT revenues and employment.

Simon Ward at Henderson makes a further point. Revisions to old GDP data show that if you look at the onshore economy and allow for the impact of an extra bank holiday, there was only one quarter, the fourth quarter of 2011, when the economy has contracted since the main recession. So there was no "double dip". So there can be no "triple dip".

He comments: "Will the triple-dippers please acknowledge their mistake, or else make clear that their phantom recessions reflect weak North Sea production, bank holidays and the impossibility of hosting the Olympics every quarter?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks