Hamish McRae: So is it time to get the message at last and start bailing out of bonds?

Economic View

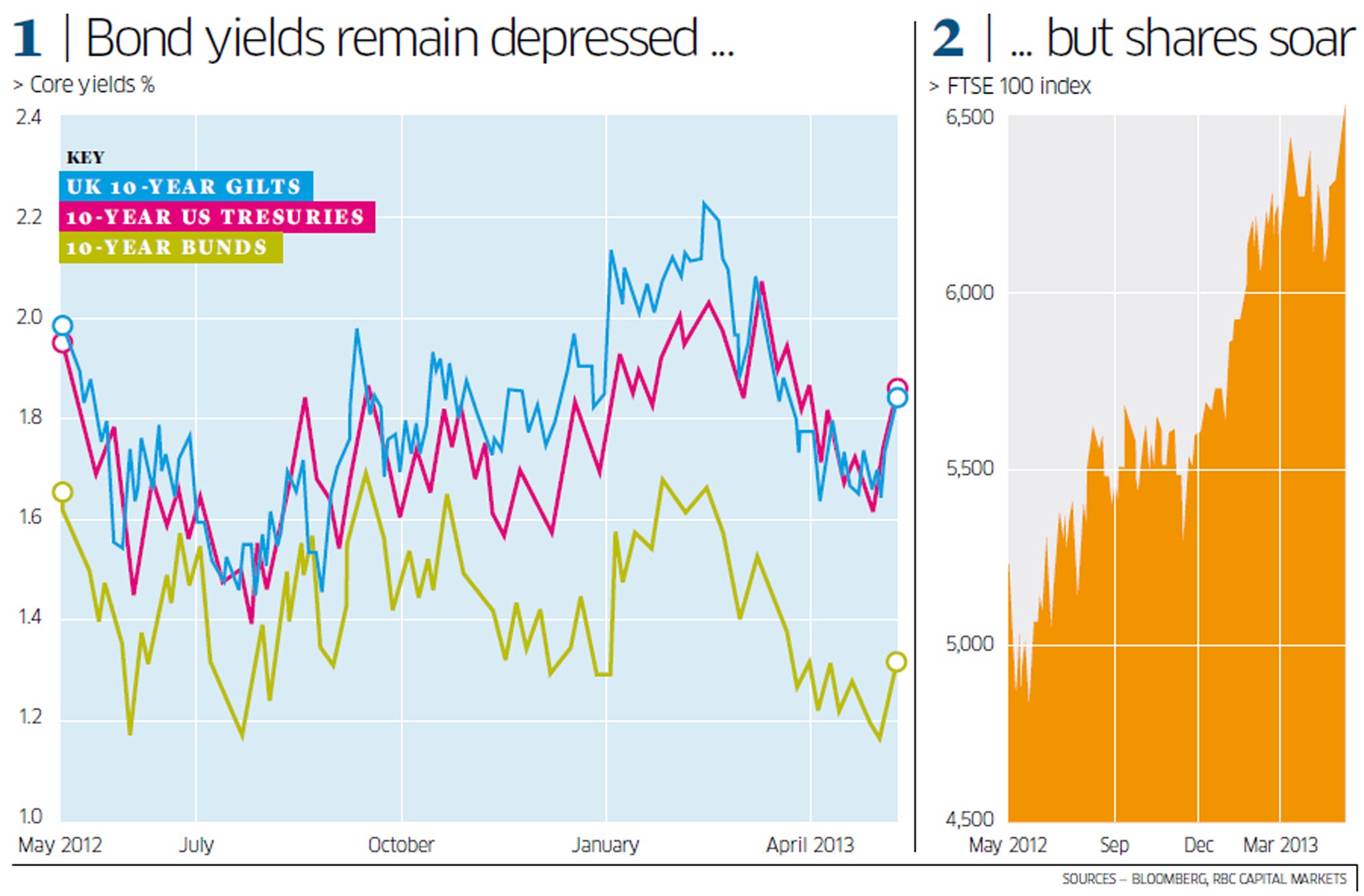

The "great rotation" is sort of happening, but not quite in the way predicted. Last summer and autumn the big idea in investment was that investors would progressively "rotate" their holdings out of bonds and into equities. Bond yields would rise (and of course prices fall), while shares would climb. Bonds, it was argued, were grossly over-priced, for long-term interest rates were exceptionally low, while shares were fairly priced, though not exceptionally cheap.

Since then there have been two broad trends. The second half of the rotation has indeed taken place in the sense that share prices have boomed. Even those of us in the "bull" camp will have been surprised by the sustained strength of the rally – witness what has happened to the FTSE 100 index over the past year, as shown in the right-hand graph.

As argued here in earlier columns there are "good" and "bad" forces behind this surge. The positive forces include gradually improving global growth, decent earnings from major companies and a reduction in fears of a eurozone break-up.

The main negative one is a sense that the central banks have printed shed-loads of money and that has to go somewhere, even if it is creating a new bubble in global equities.

Anyway, the boom has been universal, with all the major markets massively up on the year. Anyone who last autumn listened to the doubters should feel pretty soft for they will have missed a huge opportunity.

The pretty much straight-line increase in recent days does suggest that there are a lot of would-be buyers around who are worried they have missed something big and therefore will take any dip in prices as an opportunity to get some money into the market.

The other half of the switch however has only happened in muted form. There was a rise in long-term interest rates from what I feel were ridiculously low levels last summer but in the past couple of months, in the case of US treasuries and UK gilts, that's been partially reversed.

In the case of German bonds, yields are still close to their all-time lows. You can see the ten-year yields for the US, UK and Germany in the main graph.

There is a small point to be made about this, and a big puzzle. The small point is that the downgrading of the UK credit rating, with two of the three main agencies dropping our AAA status, has had zero impact on the rates at which we borrow. If anything we are able to borrow more cheaply. Similar downgrading of the US and France has also had no impact at all, again if anything the reverse. That makes you wonder really whether the events of the past five years have permanently eroded the power of the ratings agencies.

The big puzzle is why on Earth do investors lend money to governments at rates that will in all probability give them a negative real return? There are some investors who are in effect compelled to hold government bonds – some banks, pension funds and insurance companies – but for most investors this seems madness. Even many of the more canny central banks are now shifting part of their reserves out of government debt and into equities. Indeed the new phenomenon conferring added respectability to equity investment has been the central banks switching funds into shares.

But the converse does not yet seem to have struck the markets: that the fact that central banks themselves are reducing their holdings of government securities might be a bit of a sell signal for everyone else.

So where do bonds go from here? There is an overwhelming consensus that yields will rise pretty much from now onwards.

The big argument is about how far and how fast. There is a wide range of projections, with expectations for ten-year gilts in two years' time to be yielding anything from around 2.2 per cent (against 1.9 per cent now) to 3.5 per cent or even more.

I have not, however, seen anyone predicting a rout, with yields rising even to the historic crisis levels of 6-7 per cent, let alone the double-digit yields of the 1970s and early 1980s. I suspect the main reason why (aside from the fact that most fixed-interest analysts are too young to remember the 1970s) is that there is a general conviction that the money-printing exercise of the central banks will not have a significant impact on current inflation, whatever it does to asset prices. But we will have to see.

There may be a fundamental reassessment of the security of what at the moment is seen as prime sovereign debt, but we may need a formal default by a large developed country for that to happen.

Rationally there are several countries which will need to default, the most obvious examples being Japan and Italy, but this outcome could be ten years away.

Yet anyone taking the view that the second half of the great rotation is further off than many of us currently expect needs to be aware that once a trend becomes embedded it becomes very hard to shift.

If you see the current situation as similar to that of the late 1940s, when the exceptional measures needed to finance the war were being unwound, then the move out of bonds could be quite gradual.

But any investor who stuck around in gilts through the 1950s made a monumental error, and current holders should remember that.

On Friday Bill Gross, head of PIMCO, the world's largest bond fund managers, tweeted that the 30-year bull market for bonds "likely ended" on 29 April. So there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks