Hamish McRae: The big question now is to what extent global equity prices are dependent on QE and monetary policy

Economic View: The UK may be the first major country to increase interest rates

The US budget deficit deal has been done; now for the end to the taper. What does this all mean for global equities?

The fact that the markets moved hardly at all when Congress got its act together shows that the deal was already discounted. It was, in the jargon, "in the market". But is the tapering and eventual end of the monthly Fed purchases of Treasury securities, the US version of quantitative easing, in the market too? Common sense says it must be, because it has been so widely expected, but you never know until it happens – which might, by the way, be very soon.

There is a wider question here, the biggest single investment question of all right now. To what extent are global equity prices dependent, not just on QE but on ultra-easy monetary policy? To some extent they must have been inflated by the way the main central banks have been spraying the stuff around, but we don't know by how much.

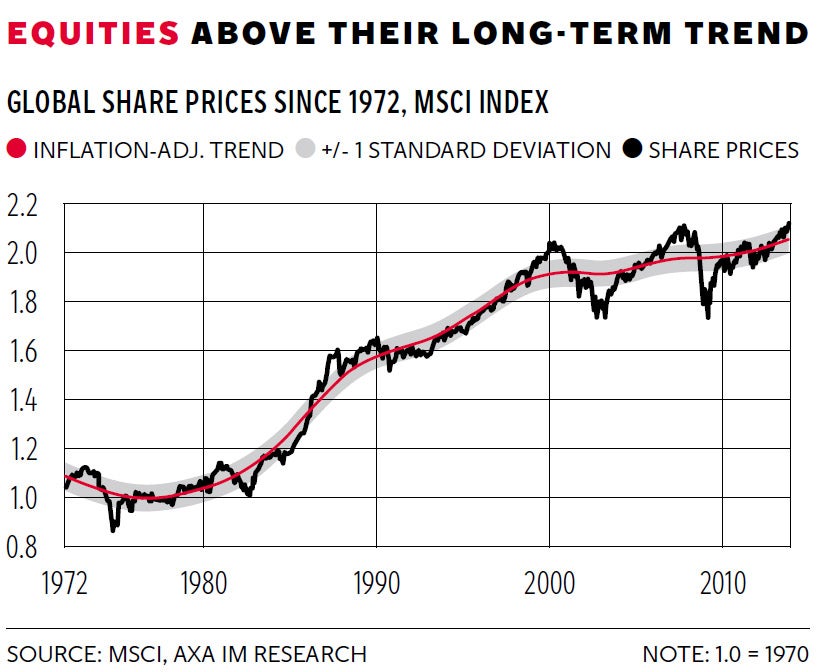

The backcloth is the very strong share markets that have developed since that awful spring of 2008. Some markets are at their all-time peak, others (including the FTSE 100) still a bit off that. But if you take global equities as a whole, they are not only close to the peak, but on quite extended valuations. You can catch some feeling for that from the graph, which comes from a presentation by Eric Chaney of AXA group. It shows global share prices in real terms (ie adjusted for inflation) since 1972 – the black line – together with a trend line in red and bands of plus or minus one standard deviation on either side, shaded in grey.

As you can see, the upward trend of share prices is still continuing but we are one standard deviation above it. We can go further above it, as we did in 1998-99 and in 2006-07, and we may well do so. But the risks are clear.

Most of the current comment from investment institutions is reasonably bullish as far as shares are concerned, though naturally much less so for bonds. A typical comment is that from Fidelity, where Dominic Rossi, its global chief investment officer for equities, believes that "2014 will continue to provide an equity friendly environment, underpinned by sustained economic progress in the US."

That would be pretty much the view of Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Its chief investment officer, Michael Hartnett, is bullish on stocks, bearish on interest rates and bonds, bullish on the dollar and property, and bearish on commodities. The US 10-year Treasury yield will rise to 3.75 per cent (which has implications for corresponding gilts), but while the great rotation our of fixed-interest and into equities continues, the potential for shares is more muted next year. It also notes that the faster the growth, the lower the stock market returns: in the UK outperformance on growth has happened alongside underperformance in equities.

As far as European shares are concerned, the bull case is slightly more nuanced. It is that the eurozone economy as a whole will become somewhat better but also that it is not so fully valued as that of the US. For example, a year ago Macquarie forecast a 15 per cent total return for equities this year. So far they have returned more than 18 per cent. It suggests another 15 per cent return for next year, driven largely by higher-than-expected earnings, which does not sound overly demanding. There are, however, huge differences within Europe. German shares are at their all-time peak, whereas while French ones have also had a good year, they are still way down from their peak.

And here in the UK? Well, the FTSE 100 has been an underperformer. It is up 15 per cent on the year to date but that compares with 19 per cent for the German DAX, and 28 per cent for the S&P 500. Part of that disparity is explained by the rise in sterling vis-à-vis the dollar, now at a four-year high, while part is the result of the high weighting of mining and other raw material companies. (The FTSE 350 index, which represents smaller companies which are more affected by the strong UK domestic economy, have done much better.) But I don't think that is a complete explanation. I think hanging over UK markets is the possibility that we may be the first major country to increase interest rates, with the first rise coming before the end of next year. November is the obvious month for that.

That would be my own view, but it is not just one journalist's opinion. A survey for Markit yesterday showed that 55 per cent of British households expect the first rise in rates to come in 2014, with one-third expecting the rise to come in the next six months. So much for the new governor's "forward guidance". People don't believe it, just as they did not believe the previous governor's efforts to talk down the pound.

Does the timing matter that much? If everyone knows that something is going to happen it may not make a lot of odds when it comes; people have already started to adjust their behaviour. We are only talking of base rates going from 0.5 per cent to, say 1.5 per cent over the next three years. British households have had to put up with much larger financial blows than that, including the poor UK performance in inflation – worse than the US or Europe. If an earlier increase in rates were to mean we would get lower inflation, then many would say: bring it on.

My guess (this is intuition rather than reason), is that global investors are prepared not just for the ending of ultra-easy money but also for a sustained upswing in the interest rate cycle. They are grown-ups, and expect a long, if bumpy, global expansion. All that would support global equities. The problem is the stretched valuation, particularly of the US market. Common-sense conclusions? The case for global equities is still positive, but not nearly as positive as it has been for most of the past 18 months. The case for UK equities may be rather stronger, as we have some catching up to do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks