Hamish McRae: The biggest poser for the new Government: where will the growth come from?

Economic Life: Policymakers assumed that the tax boost was the result of an improved structural growth rate, whereas it was the result of an unsustainable cyclical boom

If fiscal austerity has become the "new normal" across Europe, might slow growth be its partner? The best way to starting trying to think through the process that begins with the emergency Budget promised within 50 days is to separate the cyclical from the structural. We have had a boom and a slump. Now we are going to have, not a boom, but an increasingly solid recovery, starting probably next year.

We should not rule out the possibility of a double dip to the recession, for that would be completely normal, but I think by the end of next year the growth numbers should look quite strong. We need it. We are not in the position of Greece, which many of us think has accumulated debts that can never be repaid in full. But our ability both to service a doubled national debt, and to start to repay it, will turn on our ability to generate growth. If it is a problem for us, it is also a problem in even greater measure for much of Continental Europe, where relative debt levels are generally higher and growth prospects on balance probably worse. But that is bad news too: we still sell a lot of stuff there.

So we are about to begin along a difficult path, and it is worth just making it clear why we are where we are. In a nutshell, our policy-makers confused the cyclical with the structural. They assumed that the strong boost to tax revenues during the boom years was the result of an improved structural growth rate, whereas actually it was the result of an unsustainable cyclical boom.

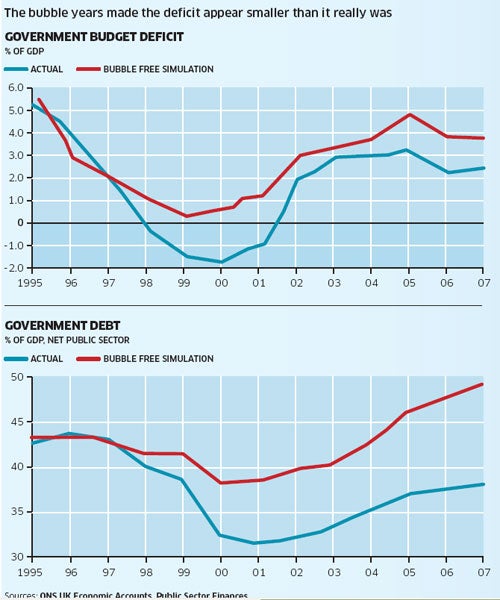

I have been looking at some work by Dr Bill Martin, a former City economist now at the Centre for Business Research at Cambridge University, which shows what would have happened to the deficit and to our debt had there not been these bubble years.

You can catch a feeling for this from the graphs. The blue lines show the actual deficit as published, the red line what the econometric model he has developed shows would have happened had growth been on a more sustainable path. As you can see, our "real" deficit never went into surplus during the 1999/2001 dip, and reached 5 per cent of GDP in 2005. Indeed during the long growth period between 2002 and 2007 we were above the Maastricht limit, whereas on the official figures were we on it or below it.

As a result, our national debt, far from dipping down to below 35 per cent of GDP as reported at the time, was really only briefly below Mr Brown's 40 per cent ceiling, and actually by 2007 – ie, well before the recession struck – was already approaching 50 per cent of GDP.

The point about this bit of history is that it shows that a cyclical boom can conceal a longer-term trend. So the question now, as the cycle moved into some sort of upswing, will be the extent to which the cycle will help us get our finances under control and the extent to which, on the other hand, the structural debt burden will hold back the cyclical advance.

This is a huge problem for the rest of Europe, too. The point was well put yesterday by Mohamed El-Erian, the chief executive officer of Pimco, a US fund manager:

"What is happening in Europe is a vivid illustration of an underlying theme of the new normal," he said. "There are structural forces overwhelming traditional cyclical ones."

Pimco believes that the debt crisis in Europe reinforces its view that there will be an extended period of below-average economic growth, even after global markets have rebounded from the financial crisis.

That seems to me to be the biggest threat to our new government. We simply won't get the growth. The reason will not so much be the fiscal drag from the need to correct the deficit. When a deficit is obviously unsustainable, as ours is, it has probably stopped giving any boost to the economy. The caution, even fear, induced by a double-digit deficit more than offsets the extra money being spent. We have to rebalance our economy and that is that. The reason is simply that it is hard to see where demand will come from. Consumers will be hit by rising taxation; most of our export markets are also likely to experience slow growth; companies will be reluctant to hire; and so on.

I have a further worry: the underlying public finances may be even worse than the present numbers suggest. There is evidence that the Revenue and Customs have been delaying tax repayments, while pushing harder to get unpaid tax in. Some capital gains tax gains will have been taken in recent months to avoid the higher taxes to come. Income tax receipts may actually fall as people cut their income as the 50 per cent tax rate comes in. Governments can put up tax rates, and this one will, but the revenues may not rise in line with the higher rates.

All this will be scrutinised by the new Office for Fiscal Responsibility, headed by Sir Alan Budd. So there will be some external verification of Treasury forecasts.

I should make it clear that once Alistair Darling was installed as Chancellor, the Treasury's assessment of the future trend of government finances improved markedly. We at last started to get robust figures rather than overly optimistic ones. I expect when the final borrowing outcome for the past financial year is revealed it will turn out to be a little worse than the £167 billion currently quoted, but only a little. The Treasury may now overestimate its ability to get the tax revenues in.

So what should we look for in the coming 50 or so days before the next Budget? Three things. First, any evidence about the buoyancy or otherwise of the economy, for growth is crucial. So we should hope for positive signs from business surveys here and elsewhere, signals from the housing market and from the consumer confidence surveys, any early news on hiring intentions in the private sector and so on.

Second, in their incoherent way, the financial markets will try and give a feeling for the solidity or otherwise of the world economy. Markets seem to have got over their Greek scare, though the medium-term outlook for heavily borrowed eurozone countries is dire. Remember that nearly three-quarters of the earnings of FTSE 100 companies comes from overseas, either in remitted profits or export receipts, so that gives a picture of the health of the world economy. If the world economy continues to recover it will pull us along with it.

And third, we should use our heads to observe how we as ordinary people are responding to the new political landscape. Are we going to be more cautious or more relaxed? Are we going to accept austerity, or are we likely to take to the streets?

I suppose what worries me most is not the reaction over the next few months, but the sense of having been cheated – of having been made financial promises that cannot be kept – that will last for years. We have to get growth going again, and a sullen electorate will find it hard to deliver that – which of course makes the deficit even harder to crack.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks