Hamish McRae: With political calamities piling up, why are markets so keen on the US?

There is one concern that even optimists need to acknowledge. The US may, indeed, default

The US government may shut down on Tuesday, the start of their new fiscal year. That is something that you might imagine people should be jolly worried about. Non-essential employees being laid off; those that are deemed essential not being paid; and if the shutdown lasts even a few days a measurable dent in fourth-quarter growth.

If you are one of the million or so employees likely to be affected, all this is doubtless a worry, yet in the US and world financial markets there seems to be hardly any concern. The chief analyst from Moody's had earlier said that that a three-to-four week shutdown would chip 1.4 per cent off fourth-quarter growth, effectively halving it, and over the past week share prices have fallen back a little. But ten-year US treasury yields at 2.7 per cent are almost exactly where they were a month ago, having nudged up above 3 per cent briefly in the interim.

This insouciance is all the more notable when you consider that this is a two-stage affair. Congress must agree a budget, but if in addition it fails to agree an increase in the US debt limit, the government will not only have a this partial shutdown; it will also run out of money around the middle of October, leading to it being unable to meet interest payments on its debt, technically a default. That, surely, would put the cat among the pigeons. So how do you account for the current calm?

The answer I think comes in three stages. The first is that everyone has got used to Congressional brinkmanship. We had, after all, the last-minute agreement that averted the so-called fiscal cliff in January this year. Taxes did go up and cuts in government spending were pushed through, yet the economy has managed to canter on reasonably swiftly ever since. The closest parallel to the present impasse may be the four-to-five week shutdown in 1995-96, which did reduce growth by an estimated 0.5 per cent in the final quarter of 1995. But in the context of the long 1990s boom, that was just a tiny blip.

I suppose it is a comment on the immediate activities of a government to say that a shutdown, even one lasting several weeks, would not in practical terms matter very much.

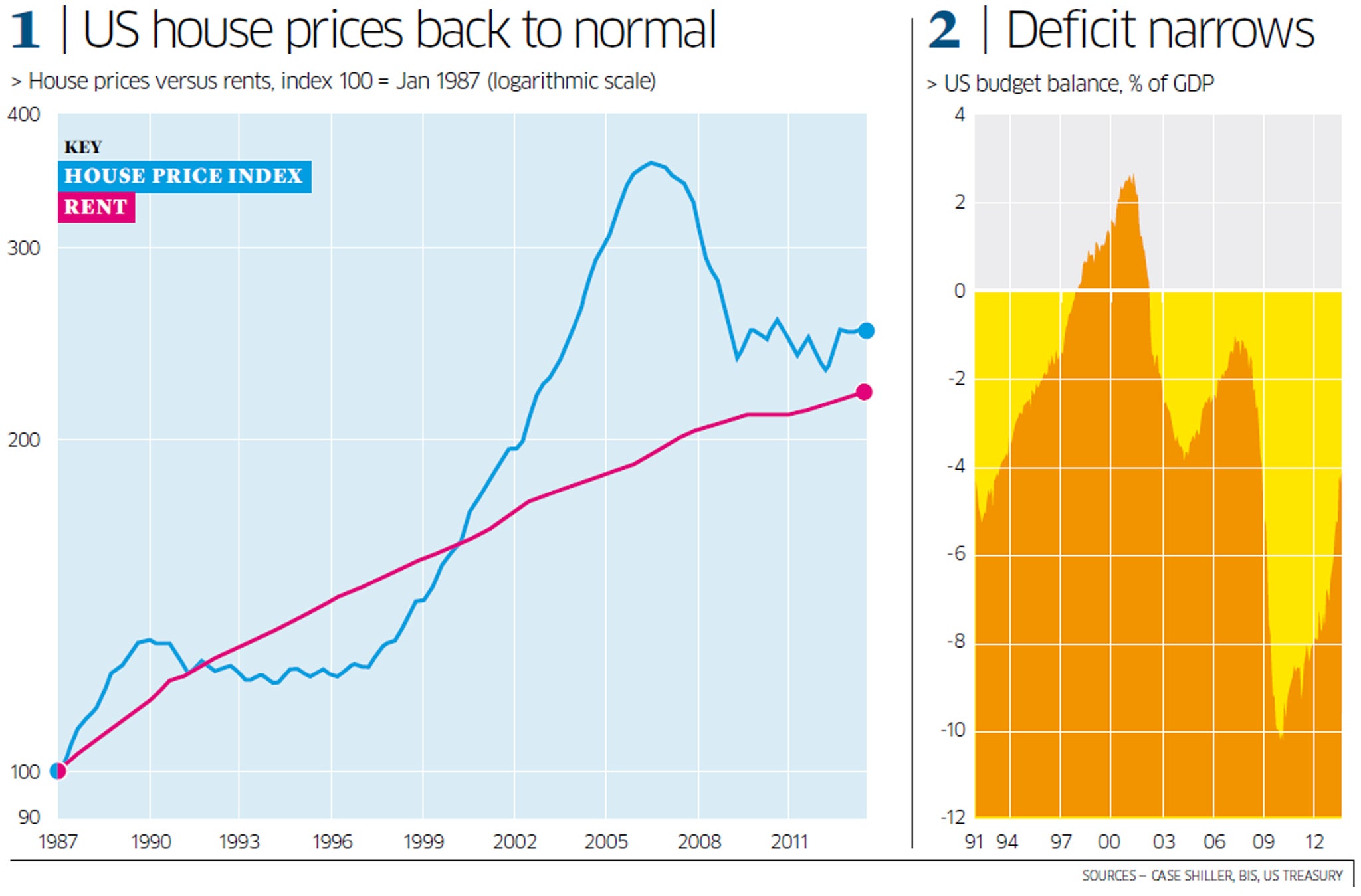

The second reason for this relaxed attitude is that the US fiscal position is improving rapidly. You can see that in the right-hand graph, which shows the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP since the early 1900s. The plunge into deficit in 2009 was serious but the US has been more successful than we have in correcting the imbalance. Their deficit is coming down to about 4 per cent of GDP, whereas our is still around 7 per cent of GDP. So the row in Congress (which is essentially over healthcare, not fiscal policy) takes place against a background of a fiscal situation that is pretty much righting itself. Encouragingly, the economy has continued to grow, generating additional tax revenues as it does, despite the fiscal tightening earlier this year – just as it did, despite the shutdown, in 1995-96.

The third reason for cheer is that the biggest single adjustment that the US had to make, to cope with falling house prices, is pretty much done. Not only have US home prices started to climb a little; they are not too far out of line with the "true" value implied by rents. I am grateful to Scott Grannis, former chief economist at Western Asset Management of Pasadena, California, for the comparisons in the main graph. The rental price is what is known as owner's equivalent rent, what the owner of a house would have paid in rent if he or she had to rent it on the open market. It used for calculating the consumer price index, among other things, and it gives a crude indicator as to whether house prices are undervalued or overvalued. So house prices are still a bit overvalued relative to rents, but not massively so.

When you consider the scale of the boom, to get back to this reasonably sustainable position without a social catastrophe suggests that this is a base from which the US economy can expect sustained growth. The housing boom and subsequent collapse made what would have always been some sort of downturn massively worse. Now housing is no longer a drag on the economy.

Put these three together and you can understand why the markets are reasonably optimistic in the face of sub-optimal politics. Are they too optimistic? There is one real concern that even the optimists need to acknowledge. It is the risk, albeit small, that the US may indeed default.

This point is made by economics team at Berenberg. They argue that though both sides are far apart on the budget debate, that ultimately they will do the necessary and agree – because the alternative, not just a shutdown but a default, would be a calamity. Both sides know this. So though the argument is likely to carry on the rest of this year, with perhaps only a small increase in the debt ceiling agreed next month, they will eventually come to an agreement.

That is almost certainly right. Rationally the US does not need to default. It is not a Greece. But politicians make mistakes. Lehman Brothers could have been rescued and the ultimate costs of doing so would have been smaller, probably a lot smaller, than the costs of letting it go under. So you have to allow for the small possibility of this becoming a hot October, hot that in the sense of things going badly wrong. Don't worry about the shutdown; worry about the debt ceiling and technical default.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks