Scottish independence: How Scotland could benefit if its big banks leave

It’s been a while since politicians have been so keen on hosting bankers. The confirmation from an array of banks yesterday that they will move their legal domiciles form Scotland to England if the “yes” campaign triumphs in next week’s independence referendum has provoked a tug of war between the two camps over financial services jobs.

The “no” campaign has presented the announcements as a massive blow to the nationalists, suggesting Scotland’s large financial sector would haemorrhage jobs and economic activity southwards if the UK broke up. Alex Salmond and the nationalists reject that, claiming the relocation of the banks would be a legal technicality and have no impact on employment in an independent Scotland.

Both positions, plainly, can’t be right? So which is it? As usual the answer is not clear cut. The financial sector is certainly very important for Scotland’s economy. It provides direct employment for around 85,000 people and 100,000 indirectly. That’s around 7 per cent of the Scottish workforce. Finance in the UK, by contrast, accounts for just 4 per cent of total employment. In Scotland finance also accounts for around 8 per cent of GDP, which is roughly in line with the sector’s contribution to output in the wider UK.

How would all that activity be affected if banks moved? In a narrow sense Mr Salmond is correct. “It is not an intention to move operations or jobs” wrote the chief executive of the Royal Bank of Scotland, Ross McEwan, yesterday, literally spelling out his position on the12,000 staff employed by the bank in the country.

As the nationalists have also pointed out, the Scottish domiciles of some of these banks are something of a fiction. Most of Lloyds Banking Group’s head office operations, for instance, are already in London, its Scottish domicile being a consequence of its ill-fated acquisition of the bust Halifax Bank of Scotland in 2009. Brass plates would certainly migrate, but it is not clear how much real activity would follow.

As for the tax consequences, corporation tax is levied on real activity, meaning that the loss to an independent Scotland would depend on how much of this departed. It is worth noting that banks are not paying much of this levy at the moment, in any case, because they are able to offset their bill with the large losses taken in the financial crisis.

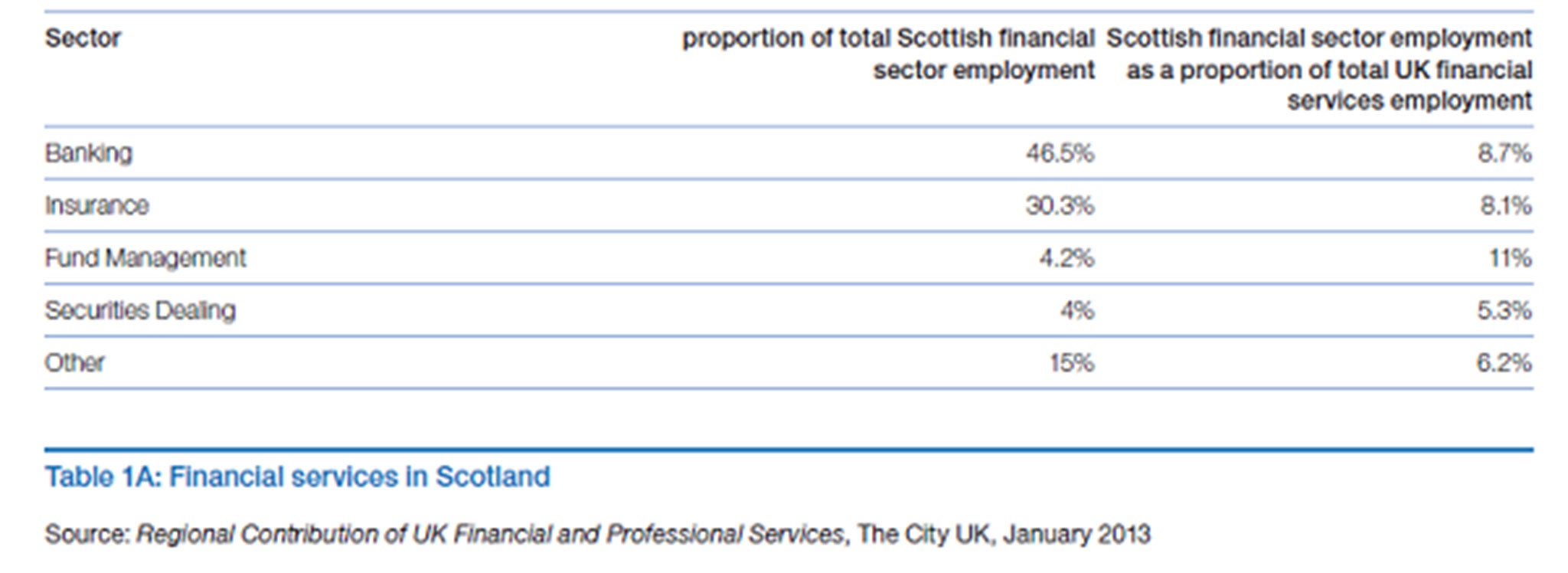

Yet there’s more to financial services than banks. Asset management companies and insurance firms make up around a third of the sector’s jobs in Scotland, as this table shows:

And there have been some noises of trepidation from these firms too at the prospect of independence. Standard Life, which employs 5,000 people in Scotland announced this week that it would move whole operations to England in the event of a yes vote. That would, inevitably, take some jobs south. Other firms might feel the need to follow.

And it’s not unreasonable for the no campaign to argue Scotland’s dense financial ecology and skills networks, which have been an inducement for firms to base operations there, could be harmed by bank migrations.

Angus Armstrong of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research also points that the banks’ domicile shifts could have a negative impact on the newly independent Scotland’s balance of payments since financial services account for 15 per cent of Scotland’s exports.

Armstrong also suspects that the UK’s financial regulator will demand that real job-sustaining banking activity, rather than just legal titles, is moved to England where it can be closely monitored. “Will the [Bank of England's] Prudential Regulation Authority be satisfied with moving a brass plate? That’s not reasonable” he says.

Yet the Scottish nationalists insist they will make it more attractive for financial firms to expand their operations in Scotland post-independence by investing in skills and infrastructure. And it is notable that Martin Gilbert, the founder of Aberdeen Asset Management and one of the big beasts in the industry, has said he doesn’t think much of the no campaign’s warnings of financial disaster if Scots vote yes. As with so many aspects of the debate about Scotland’s future, a huge amount depends on how a post-independence government behaves and the detail of the divorce settlement.

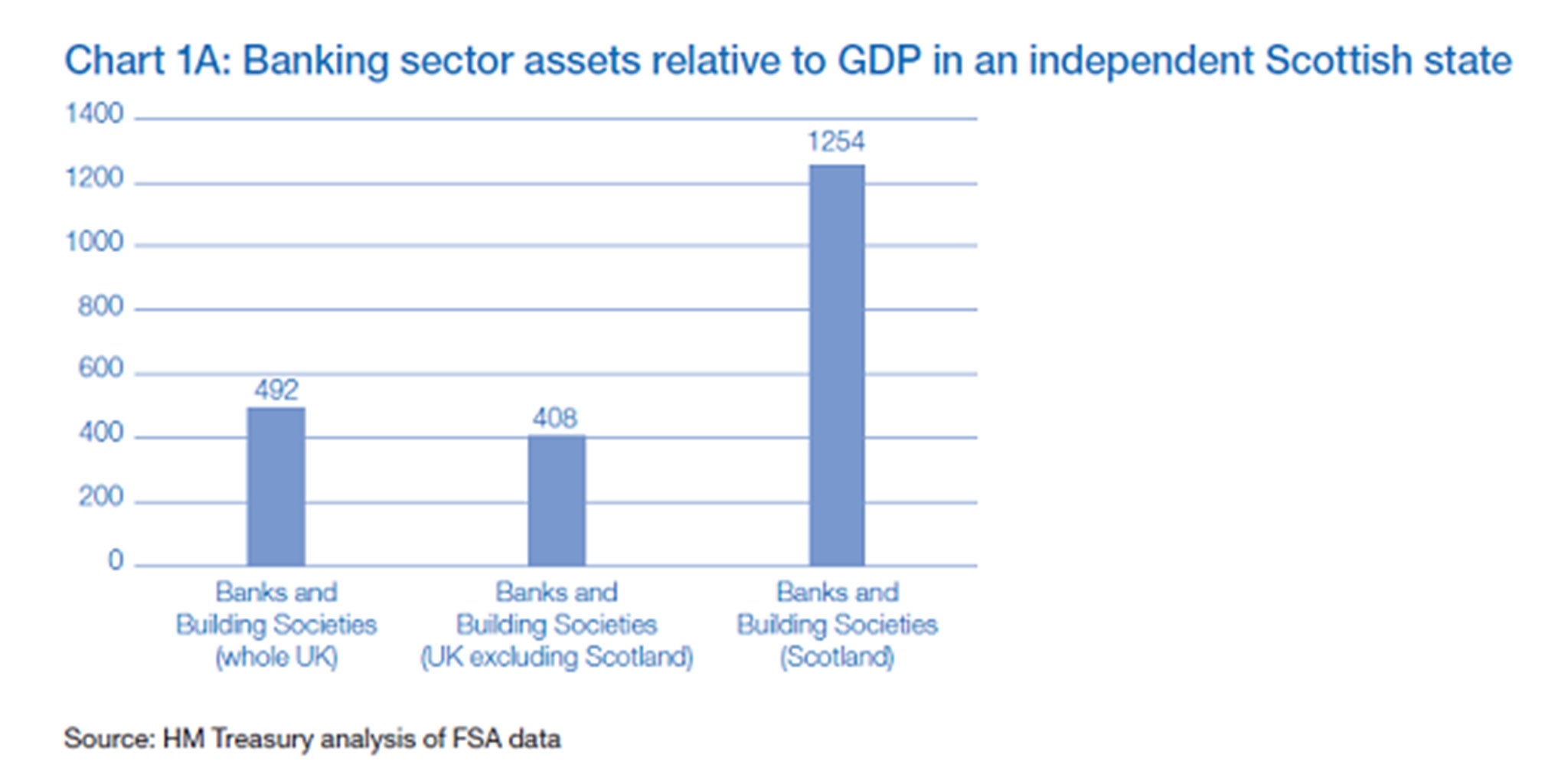

But there’s an irony in this latest twist in the tussle, which is that the fiscal position of an independent Scotland could also look better if these large banks did re-domicile. They have vast balance sheets, worth more than twelve times Scotland’s £150bn GDP:

By moving their domiciles to England these institutions would, explicitly, be the problem of London, rather than Edinburgh, in the event of a future 2008-style financial crisis.

The Governor of the Bank, Mark Carney, noted this week that countries which adopt a foreign currency (as Mr Salmond has said an independent Scotland would adopt sterling) tend to hold foreign currency reserves worth at around 25 per cent of GDP in order to guarantee domestic financial stability. And if they also host large banking sectors holdings shoot up to more than100 per cent of GDP.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks