George Osborne's original deficit reduction target finally achieved but more than two years late

Current budget actually went into surplus in November 2017, according to Office for National Statistics

The original austerity deficit reduction target set by former Chancellor George Osborne has finally been achieved, according to official figures – but more than two years after the original target date, reflecting the deeply disappointing performance of the overall economy since 2010.

In June 2010 Mr Osborne committed the coalition to reaching a surplus on the state’s current budget (which covers day-to-day state spending and excludes infrastructure investment) by 2014-15. And he mandated a severe squeeze on public spending and a hike in VAT in order to achieve it.

Labour and many academic economists warned this pace of fiscal consolidation, while interest rates were still close to zero and the recovery was not assured, could potentially do more harm than good by dampening overall GDP growth and also risked tipping the economy back into recession.

The Office for National Statistics reported last month that there was a £15bn surplus on the current budget in January, following several months of stronger than expected tax revenues.

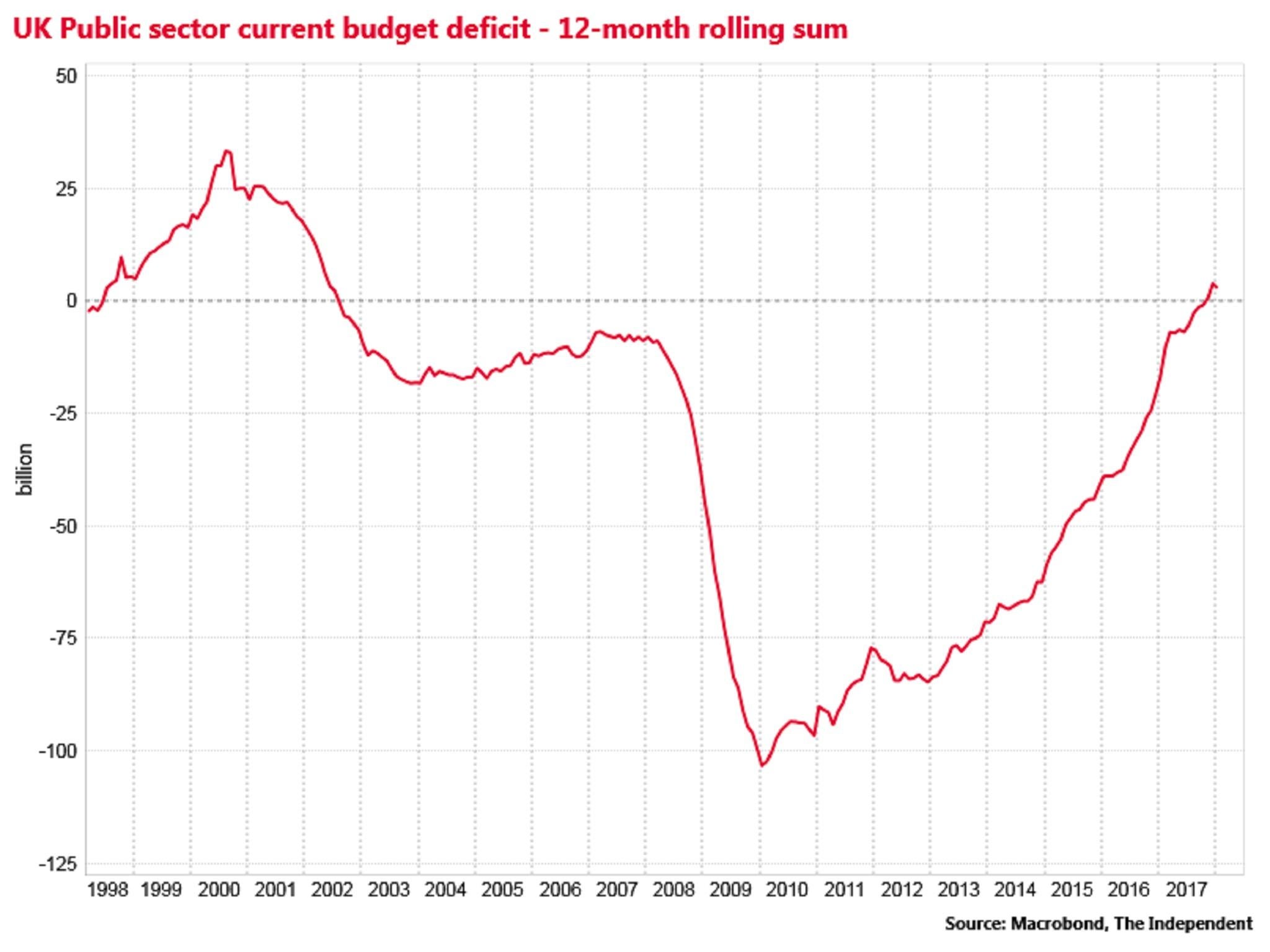

And on a 12-month rolling sum basis, the current budget actually went into surplus in November 2017.

But it was not highlighted by the Treasury at the time, perhaps because it occurred more than 24 months after originally pencilled in and because Mr Osborne himself subsequently set a much stricter target for public finances, to secure a surplus on the entire budget, including public investment, by 2020.

That stricter target was widely criticised by economists for its deliberate failure to carve out productivity-enhancing investment spending.

Mr Osborne’s successor, Philip Hammond, ditched it when he was appointed to the Treasury in 2016.

Back in surplus

The current budget deficit peaked at £100bn in 2009-10, mainly reflecting the hit to tax revenues from the recession.

Jonathan Portes, a professor of economics at King’s College London, and one of the most prominent critics of Mr Osborne’s original fiscal consolidation, stressed it was always the excessive pace of consolidation that was the problem, not the current budget surplus target itself.

“Osborne’s original target, of balancing the current budget, was never that controversial. Indeed it differed only marginally from Gordon Brown’s, Ed Balls’, or the current Labour leadership’s. It was always the pace and timing of fiscal consolidation, front-loading deficit reduction at a time when it was neither necessary nor desirable, that many economists questioned,” he told The Independent.

“The desperately slow pace of productivity and wage growth since then doesn’t in itself prove we were right, but it’s impossible to claim that the UK’s macroeconomic performance since the crisis has been anything but very disappointing. Meanwhile, even though Osborne’s original rule didn’t stop the government taking advantage of historically extremely low interest rates to invest, he chose not to: a decision which was clearly wrong at the time and looks even worse in retrospect.”

According to the latest data, the UK did not lapse back into recession during the consolidation of the Osborne years, but GDP growth was still extraordinarily weak by comparison with the pace of previous UK recoveries from recession and certainly feebler than expected in 2010.

Mr Hammond’s current fiscal target is merely for the cyclically-adjusted budget deficit to be below 2 per cent in 2020-21 and to balance the books by around the middle of the next decade.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) at last November’s Budget ruled this latter objective looked “unlikely” to be met, as it drastically downgraded its productivity growth and tax revenue forecasts.

It said that, on current trends, it was possible the overall deficit would not be cleared until the 2030s.

However, public finances this year have been notably stronger than the OBR expected in November.

At that point the official forecaster was anticipating the UK’s current budget deficit to still be around £6.2bn in 2017-18, around 0.3 per cent of GDP, which now seems likely to be too pessimistic.

The UK’s current budget surplus was first reported by the Financial Times on Thursday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments