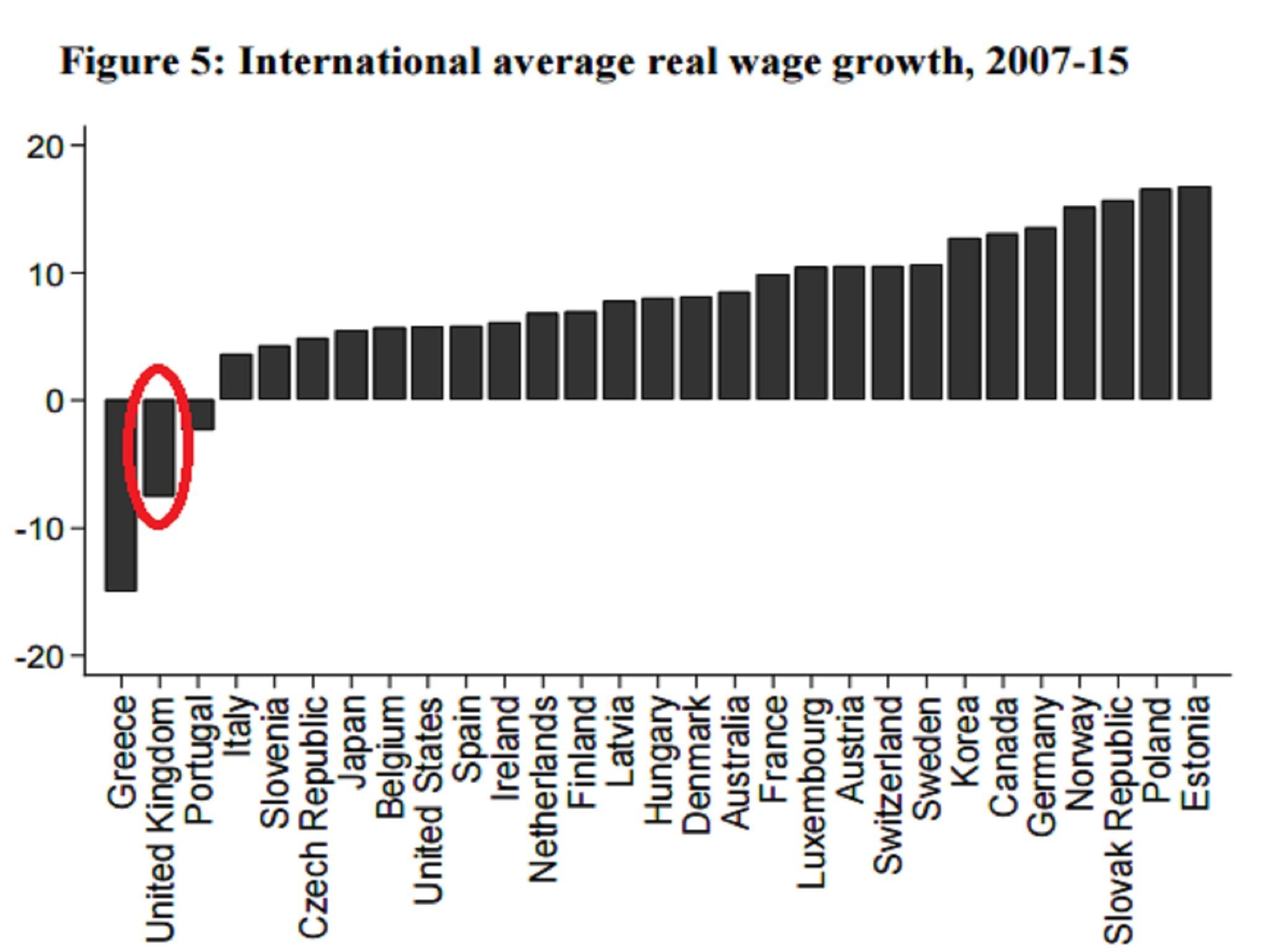

The chart that shows UK workers have had the worst wage performance in the OECD except Greece

The LSE's Centre for Economic Performance shows that average wages for British workers, when adjusted for inflation, fell by more than 5 per cent between 2007 and 2015

The UK has suffered the biggest drop in average real wages of any OECD country except depression-wracked Greece, according to a pre-general election analysis published by the London School of Economics.

The LSE's Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) uses OECD data to show that average wages for British workers, when adjusted for inflation, fell by more than 5 per cent between 2007 and 2015,

The only member of the OECD group of nations that saw a worse performance was Greece, which has seen its economy shrink by around a quarter since 2008, thanks to massive austerity and the prospect of the country crashing out of the eurozone.

Second worst in the OECD

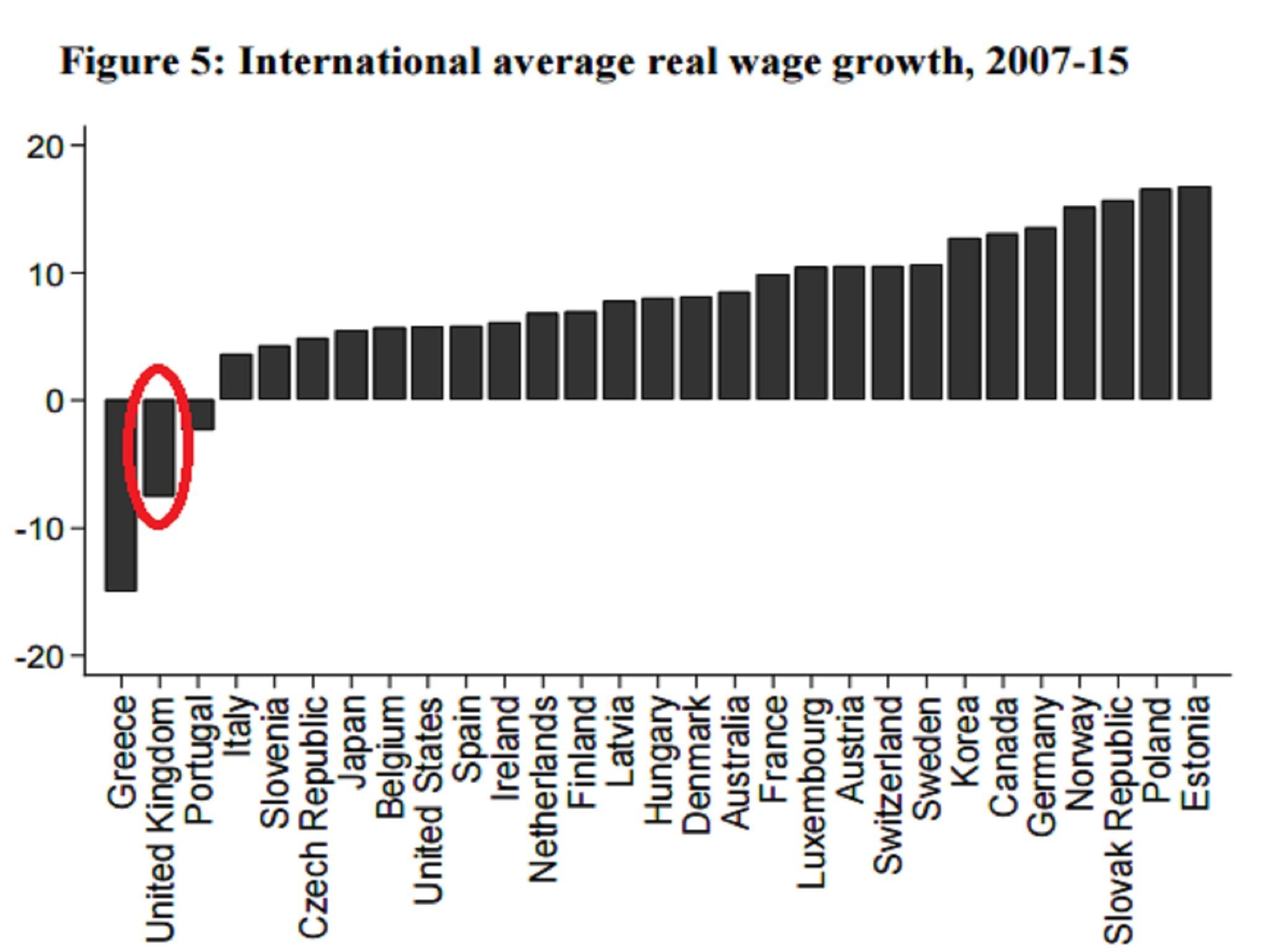

Real wages in the UK began to grow again in 2015 and 2016 as inflation fell to below zero.

But the spike in consumer prices in recent months, owing to the the slump in the value of sterling in the wake of last June's Brexit vote, means that real wages in the UK are now falling again.

Nominal average wage increases remain well below the pre-financial crisis rates of around 4 per cent a year, with the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics showing total annual pay growth of just 2.4 per cent.

Turning negative again

Most economists suspect that companies are unlikely to offer wage settlements higher than absolutely necessary to retain staff when faced with the deep uncertainty over future trade created by Brexit.

Europe is the destination for just under half of the UK's exports.

The Conservatives and Labour have both pledged to increase the minimum wage - with Labour planning to take it up to £10 an hour for over 18 year olds - but the CEP report's authors, Rui Costa and Stephen Machin, point out that this would only raise wages for lower paid workers, rather than those on average wages.

"It is not straightforward to see how proposed policies contained in the manifestos of all parties could enable future pay growth for all workers", they argue, also noting that the higher minimum wage will increase the cost base of firms, with uncertain implications for hiring.

In a separate CEP report, Costa and Machin, along with David Blanchflower, argue that "the future prospects for real wage growth do not look good".

The Bank of England, in its May Inflation Report, projected a pick-up in average wage growth of 3.5 per cent in 2018 and 3.75 per cent in 2019.

But the CEP authors dismiss this as "much too optimistic", pointing out that the Bank has been forecasting a similar bounce back in nominal wage growth since 2013 and it has not materialised.

"The Bank of England needs to gain a better understanding of what has been happening in the UK labour market," they argue.

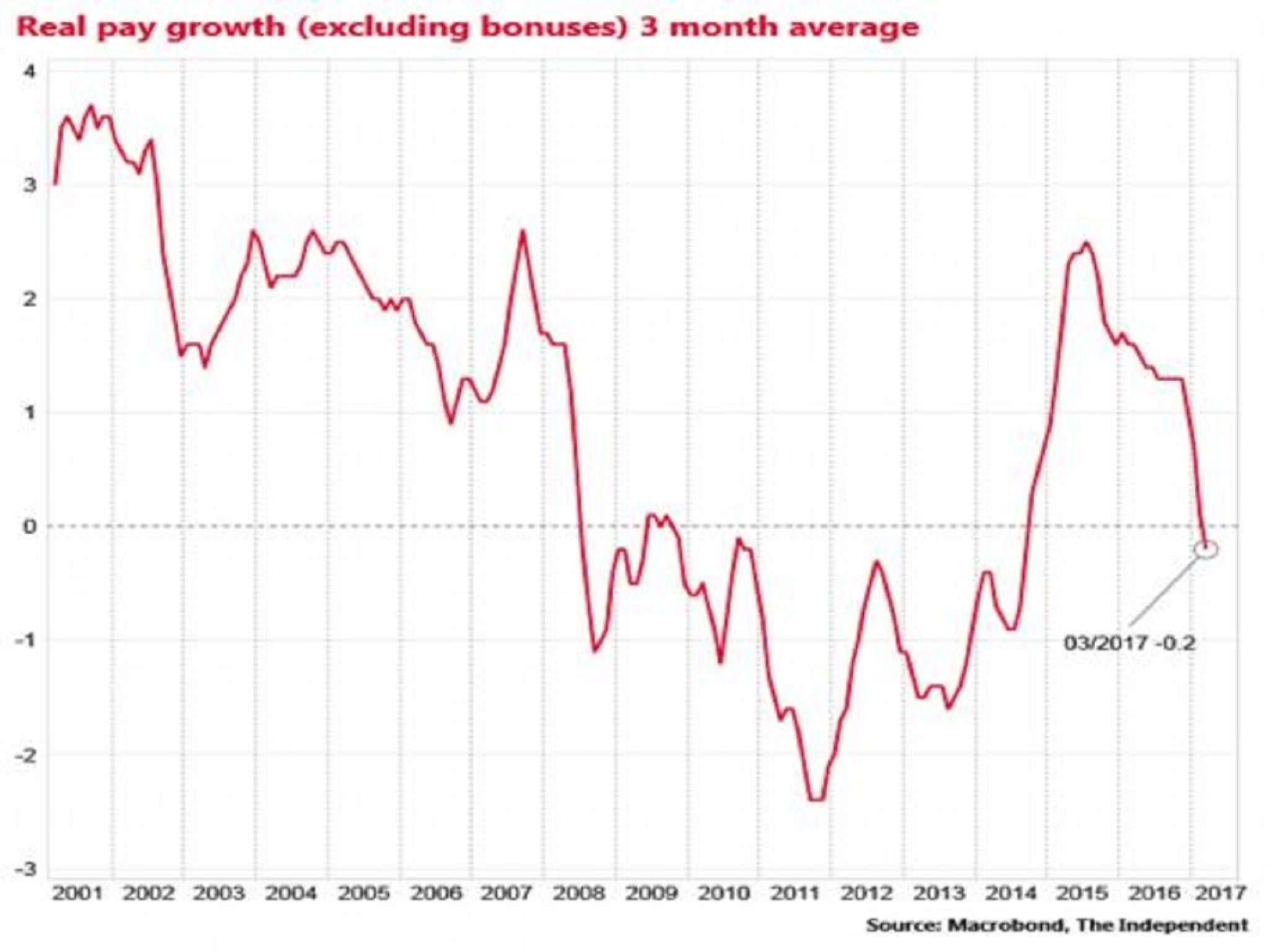

The CEP report also emphasises that it is the wages of young workers aged 18-21 who have suffered the most since the financial crisis, with their real weekly wages down 16 per cent between 2008 and 2016.

Young have borne the brunt

Consumer price inflation jumped to 2.7 per cent in April, its highest since 2013.

Meanwhile, the UK's GDP growth slowed to 0.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2017, as rising prices hit household spending.

This was the joint worst performance in the G7.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments