Astronomers make huge discovery under Saturn’s moon that could change search for alien life

NASA’s planned Dragonfly mission is expected to provide more clarity on the moon’s innards

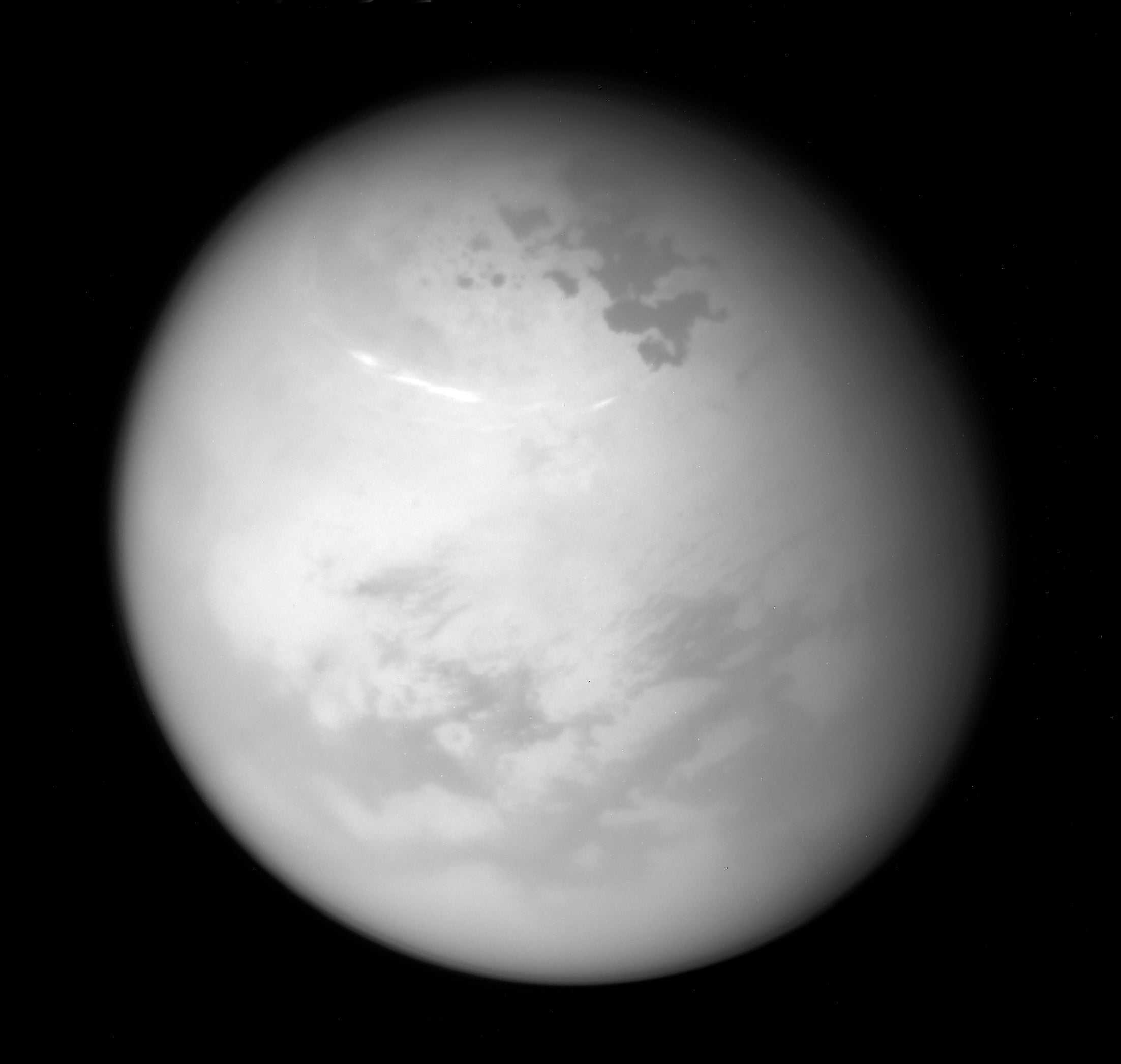

Saturn's giant moon Titan may not have a vast underground ocean after all.

Titan may instead hold deep layers of ice and slush more akin to Earth’s polar seas, with pockets of melted water where life could possibly survive and even thrive, scientists said Wednesday.

The team led by researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory challenged the decade-long assumption of a buried global ocean at Titan after taking a fresh look at observations made years ago by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft around Saturn.

They stress that no one has found any signs of life at Titan, the solar system’s second largest moon spanning 3,200 miles (5,150 kilometers) and brimming with lakes of liquid methane on its frosty surface.

But with the latest findings suggesting a slushy, near-melting environment, “there is strong justification for continued optimism regarding the potential for extraterrestrial life,” said the University of Washington’s Baptiste Journaux, who took part in the study published in the journal Nature.

As to what form of life that might be, possibly strictly microscopic, “nature has repeatedly demonstrated far greater creativity than the most imaginative scientists," he said in an email.

JPL’s Flavio Petricca, the lead author, said Titan’s ocean may have frozen in the past and is currently melting, or its hydrosphere might be evolving toward complete freezing.

Computer models suggest these layers of ice, slush and water extend to a depth of more than 340 miles (550 kilometers). The outer ice shell is thought to be about 100 miles (170 kilometers) deep, covering layers of slush and pools of water that could go down another 250 miles (400 kilometers). This water could be as warm as 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius).

Because Titan is tidally locked, the same side of the moon faces Saturn all the time, just like our own moon and Earth. Saturn’s gravitational pull is so intense that it deforms the moon’s surface, creating bulges as high as 30 feet (10 meters) when the two bodies are closest.

Through improved data processing, Petricca and his team managed to measure the timing between the peak gravitational tug and the rising of Titan’s surface. If the moon held a wet ocean, the effect would be immediate, Petricca said, but a 15-hour gap was detected, indicating an interior of slushy ice with pockets of liquid water. Computer modeling of Titan’s orientation in space supported their theory.

Sapienza University of Rome’s Luciano Iess, whose previous studies using Cassini data indicated a hidden ocean at Titan, is not convinced by the latest findings.

While “certainly intriguing and will stimulate renewed discussion ... at present, the available evidence looks certainly not sufficient to exclude Titan from the family of ocean worlds," Iess said in an email.

NASA’s planned Dragonfly mission — featuring a helicopter-type craft due to launch to Titan later this decade — is expected to provide more clarity on the moon’s innards. Journaux is part of that team.

Saturn leads the solar system’s moon inventory with 274. Jupiter’s moon Ganymede is just a little larger than Titan, with a possible underground ocean. Other suspected water worlds include Saturn’s Enceladus and Jupiter’s Europa, both of which are believed to have geysers of water erupting from their frozen crusts.

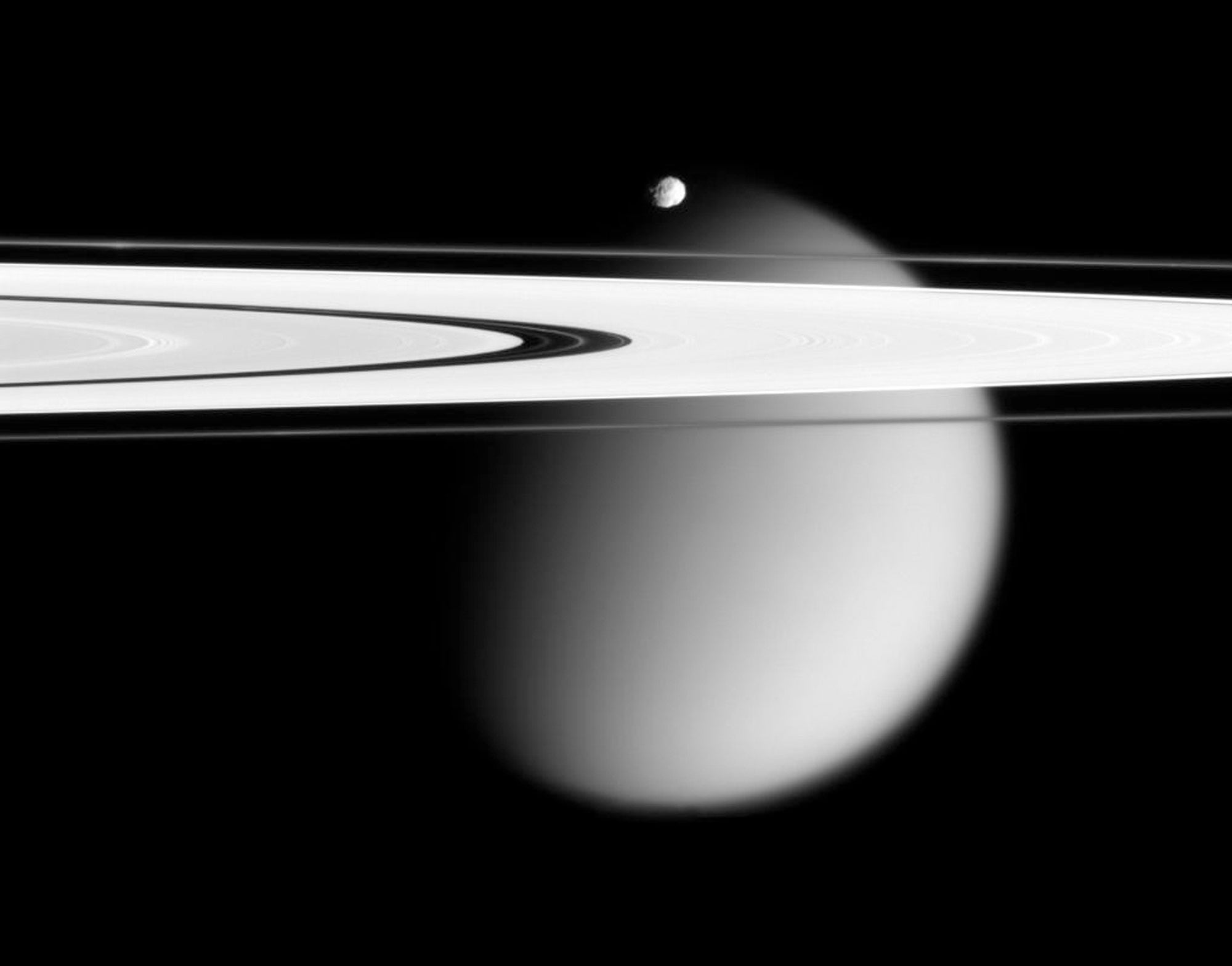

Launched in 1997, Cassini reached Saturn in 2004, orbiting the ringed planet and flying past its moons until deliberately plunging through Saturn’s atmosphere in 2017.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks