The sinister role of ‘black-pilling’ in the murder of Charlie Kirk

As the motives of the suspected assassin are still being investigated, markings on the bullet casings point to a dark movement in meme culture – where young people fantasise about disrupting and destroying the world through chaos. Chloe Combi reports

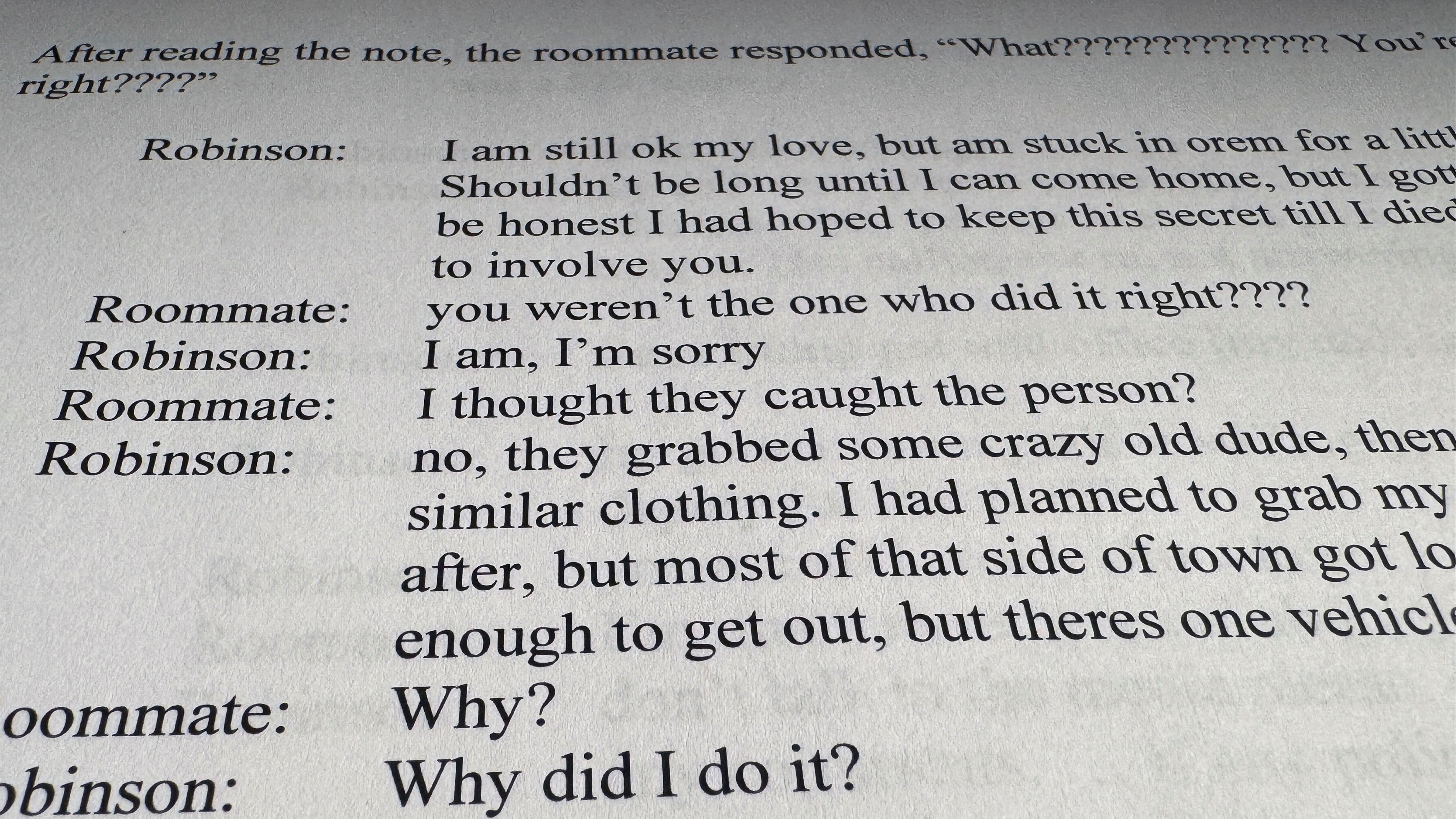

In the reporting of the assassination of Charlie Kirk, who was murdered in front of mostly college- and university-age students on 10 September at Utah Valley University, many have rushed to ascribe both motive and political ideology to Tyler Robinson, who has been charged with his murder. However, much of this has been wide of the mark – hugely missing the point about the strange and deeply complex online world that 22-year-old Robinson, and many youngsters like him, was immersed in.

Online subculture shot into the global conversation in March 2025 when the Netflix hit show Adolescence brought the term “red-pilling” into the mainstream. In the broadest terms, red-pilling means having your eyes opened to a hidden or uncomfortable truth, often about politics, society, or gender. The term is frequently used in far-right or conspiracy theory communities to describe someone being “liberated” from notions of equality, feminism, and “wokeness”. But what this conversation missed was how “black-pilling”, the darker and stranger cousin of red-pilling, is an even bigger threat – and is present in both far-right and far-left online culture.

From the many conversations I’ve had with Gen Alphas I have worked with, black-pilling tends to take two forms: nihilistic and anarchist. The first is the belief that absolutely nothing matters at all (which is why black-pillers are often dismissive of red-pillers, because that suggests a belief in someone or something). The second is a desire to disrupt and destroy the world through chaos.

The writer Ryan Broderick – who is highly knowledgeable about these online worlds and writes brilliantly about the black-pill universe in his Garbage Day Substack – recently brought the term “accelerationist” into this discussion. Describing it on Tim Miller’s podcast, he said it means “wanting to cause chaos and hurt people to speed up what they see as the downfall of society, because they don’t like it, or think it’s not helping them and is broken already”.

Robinson’s motives are still being investigated, but what we do know is that black-pilling and its intersecting offshoots are steeped in the language of meme culture. Meme culture – a way of signalling meaning through culturally understood symbols or in-jokes – was evident in markings on the casings of bullets found in the rifle used to fire at Kirk.

They carried engravings referencing “OwO,” often linked to furry culture; “Bella Ciao”, currently popular in gaming culture; and “if you read this you are gay, lmao” – a phrase widely used by kids and teens online and offline, often as a smirk at outsiders, particularly older people, who don’t understand the world and language they inhabit.

Memes also have layers upon layers of meaning, interpreted differently by different groups. They have appeared in many recent high-profile acts of violence, including the Christchurch mosque attack by Brenton Tarrant, the Charleston church shooting by Dylann Roof, and Luigi Mangione’s killing of CEO Brian Thompson.

Many perpetrators of modern violence are young men embedded in intense online communities such as Twitch and 4chan – where many memes originate. In some cases, the violence itself gets livestreamed on these platforms.

So, what does this have to do with your kids and teenagers? If they love gaming, howl with laughter at the “67” trend currently doing the rounds, or spent most of last summer yelling “skibidi toilet”, then quite a lot. This is not to say that if your child loves gaming or speaks in memes, they’ve been black-pilled or even red-pilled. But it does mean they exist in an ecosystem where, at the far end, violence and mass murder are filtered through irony and dark humour. And many within it hold contempt for a world they feel has wronged them.

If a youngster plays games and exists in communities on Discord or Telegram, they are potentially exposed to dangerous narratives – groups Broderick flags as the “Com network” and others, which he explains “recruit vulnerable young people around the internet, including inside multiplayer games like Minecraft and Roblox.”

He says: “They encourage their members to commit horrible crimes with the promise of internet clout, intentionally using conflicting political messages to obscure any larger motive besides inspiring other members of the group to do the same.”

Craig*, 19, who is deeply involved in the “far end” of the gaming world, told me he first got into it through Minecraft in his pre-teen years. Explaining the appeal of meme culture and black-pilling, he subscribes more to the nihilistic view than the anarchist or accelerationist one. He has no political affiliation, right or left, but says he admires Mangione, the prime suspect in the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Thompson. The shooting took place in New York City on 4 December 2024, and was met with a mixture of concern, fascination, and – in some quarters – surprising admiration.

“It’s hard to explain, but our view is at least an honest one. We are both fed and totally fed over in every way. Why should I care about trying to believe in or save or get worried about anything or anyone? We want it all to burn and can at least have a laugh while we watch it happen.”

Craig’s worldview may seem extraordinarily bleak, but worryingly, it is shared by a surprising number of Gen-Zers and, increasingly, Gen Alphas. Many parents saw this at first hand in their teen children’s reaction to the assassination of Kirk. Instead of horror at watching a murder in real time, many revelled in it – replaying and sharing the footage, and even creating darker memes from an already horrific event.

So, how can we protect young people from online extremism and recruitment? The obvious step is to ensure your child or teen has a life beyond the screen. In 2024, Gen-Zers averaged around six hours of screen time per day. Nearly half (48 per cent) of 16- to 24-year-olds also said they spent “too long” on social media. Teenage boys are now spending more time playing video games than they are in school. That’s according to a survey of more than 1,000 parents of seven- to 17-year-olds, conducted by gambling-addiction charity Ygam and published by Mumsnet. The survey found that 15- to 17-year-olds spend, on average, nearly 34 hours a week gaming.

Having friends, hobbies, and communities in the real world is the greatest protection against online radicalisation. It shows young people from an early age that, despite the challenges they undoubtedly face, the world can still be a good place, with people and things worth living for and believing in.

It’s also incumbent on government and wider society to ensure in-real-life experiences and opportunities are accessible to all young people, whether through youth clubs, sports clubs, or safe and welcoming third spaces.

If your child or teen games or spends too much time online – which is almost all of them – the key questions are where and for how long. Spending hours immersed in online worlds like Twitch, TikTok, or Telegram doesn’t benefit any impressionable, developing person. An obsessive need for privacy or secrecy when gaming or online is often the clearest warning sign that they have something to hide – and parents should make it an absolute priority to find out (sensitively) what that is.

We all need to really listen to what our young people are saying. If a young adult suddenly voices extreme views about gender, race, or equality that you know didn’t come from you – or if they crack jokes about, or even celebrate, shocking or terrible stories in the news – the chances are those views are being shaped online. That’s a red flag to investigate what spaces or people are influencing them.

Most parents and carers now have the “porn talk” with their children and teens. This needs to be widened into the “content talk”, where you try to figure out what they’re watching, who they’re listening to, and who may be influencing them. With the caveat, of course, that you will never fully understand their online worlds if you are not a digital native.

Ryan*, 16, recently recounted to me, laughing: “My dad was so obsessed with being ‘down’ with memes and especially who Pepe the Frog ‘was’. We got sick of trying to explain, and him not getting it, so we told him Pepe had gone full circle and was now a feminist meme meaning ‘no boys allowed’ online. We heard him telling his mates this at their dinner party and they were all like, ‘Oh really, he’s feminist now, isn’t that interesting,’ and we were just dying upstairs. Especially as they’ll probably tell their friends and it’ll cause even more confusion.”

It was ever thus that adults trying to get down with the kids often get it wrong. One of the funniest stories from the Nineties is when Megan Jasper, then 25 and working for Caroline Records, gave a New York Times journalist a “grunge lexicon” she made up on the spot. The NYT printed it in good faith, believing kids were using terms like “wack slacks” (ripped jeans), “lamestain” (uncool person), and “harsh realm” (bummer). Much to the hilarity of the grunge scene, it continued to be used with various layers of irony.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes. Only now, 30-plus years later, the stakes feel much higher and the culture much darker. And when murder becomes a joke, no one should be laughing any more.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks