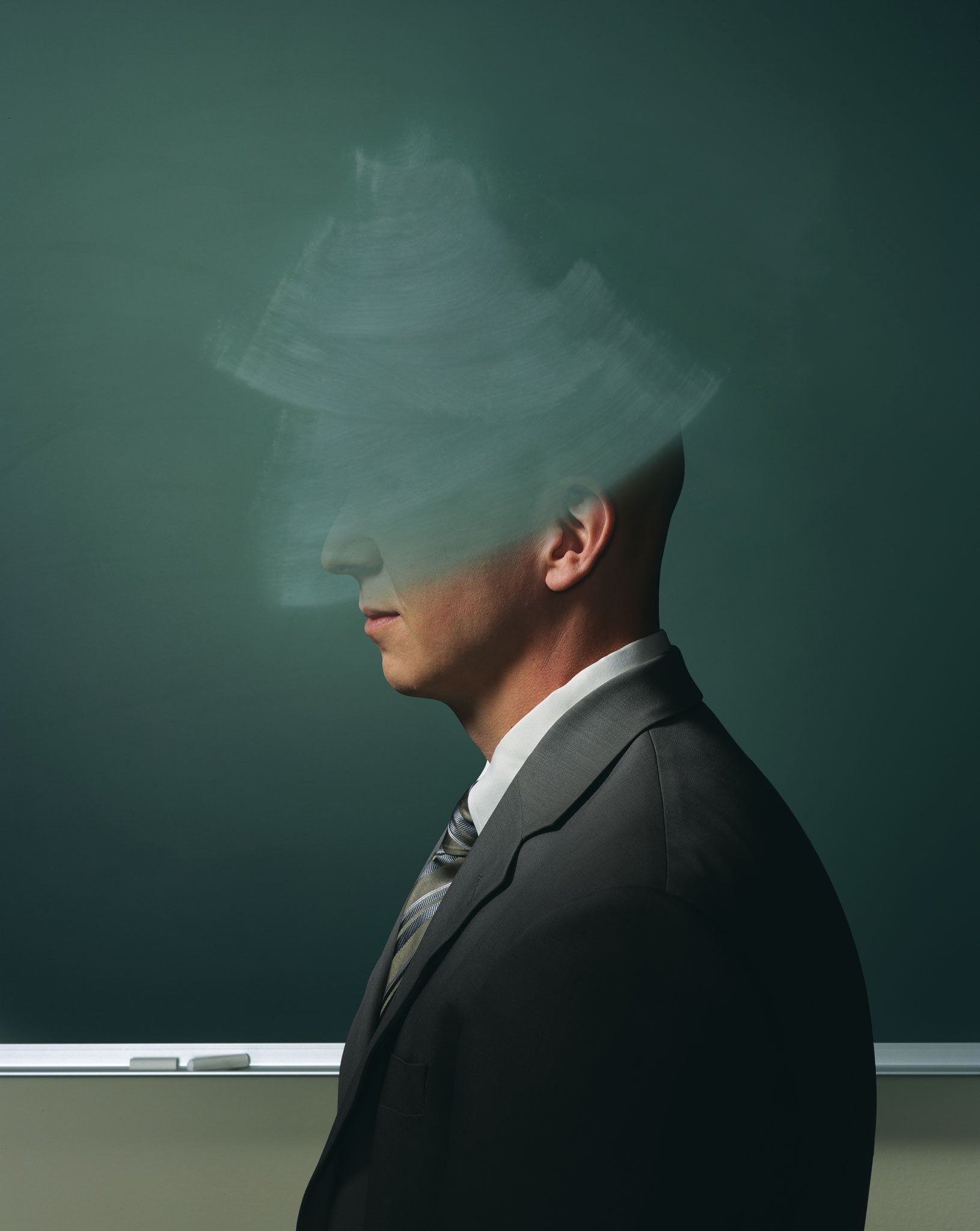

A teacher speaks out: 'I'm effectively being forced out of a career that I wanted to love'

When Sam Burton began teaching three years ago, he was determined to thrive. But after spells at an academy and a special educational needs school, he's had enough. Here, he tells the story of how even an energetic young teacher can struggle with the demands of modern teaching

It's hard to be a good teacher. It means planning weeks' worth of lessons in detail. It means covering the needs of every student, whether they're dyslexic, or don't speak English as their first language, or are high achievers and so on.

Being a good teacher means uncovering themes which will engage kids, trawling websites and libraries for films and texts as stimuli. It entails writing four different intentionally-flawed versions of a suspenseful story for them to modify in their first lesson, and five different tiers of riddles about 3D shapes for them to tackle in the second, all before 8am.

It means using outdated software to create worksheets with seven different cartoon characters to motivate students with severe learning difficulties, and spending break times enlarging these for students with visual impairments.

It means composing science songs to the tune of The Gap Band's "Oops Upside Your Head" at nine in the evening. It requires giving each student feedback every day, verbally and in writing, in each subject. It necessitates arranging and booking trips, often at lunchtime. It needs people to deliver lessons with enthusiasm and energy and flexibility all day, and to call upon reserves of patience if students are challenging.

In some of the classrooms I have taught in, this might range from students being rude, to hitting, scratching and biting on a daily basis.

Fortunately, I am excellent at doing all of the above and even enjoy it, though it leaves me physically drained and marinating in cortisol come 4pm.

Regrettably, it's not so simple. At the end of the school day, I should be checking how students did that day, giving them feedback and preparing the next day's lessons. This is why I entered teaching – to get young people to enjoy learning. This alone would ensure I stay in the building until past 6pm, which would be taxing but OK. Yet there is a range of other duties that I can be reprimanded for not fulfilling, which I then end up doing instead of preparing lessons.

I am expected to input assessment data into spreadsheets and copy it into other programs click by click, working out manually whether a percentage equates to a 'P6c' or a 'P6b'. (Data which might have been massaged by successive teachers pressured into 'generous' assessment.) I assess work that has already been assessed by completing lavish 'Next Step' stickers to satisfy Ofsted (this is in a special educational needs school where students cannot read).

I complete incident reports, carry out teaching assistant appraisals, produce three types of reports when one would do, file students' work, produce reports on attendance, and monitor a subject area to ensure others' planning and teaching is high quality. Some of these tasks are necessary, while some represent repetitive, inefficient paper chasing for the eyes of inspectors. Anyway, the point is I can't do all of them.

The current teaching culture – at least where I've worked – is that it's normal to work evenings and weekends, despite starting at 7.30am. Not the easing-yourself-into-work-over-your-emails sort of 7.30am start – it's the "If I haven't got resources ready for six different lessons by 8.45am, I'm going to have a terrible day and possibly get in trouble for having a terrible day" sort.

This is compounded by utter frustration that the reason I'm scrabbling around frantically when it's still dark outside, and exhausted and stressed during lessons, is that I was prevented from doing the basics of my job by the aforementioned administrative burden.

The workload is un-audited. New duties are not assessed for the effect they will have on existing workload. There is an implicit (and offensive, frankly) assumption that I am not already working to capacity – that when a new format for reports is introduced which will require an extra 15 hours of work over a two-week period, that I have 15 more hours spare. I have discussed the impact this has on teaching with my managers and been told simply that it is not allowed to have an impact; teaching standards are non-negotiable regardless of workload. It was explained to me that, "You can't assume I know what your workload is like" by a senior teacher.

I work 50 to 60 hours a week, yet am judged three times per year in classroom observations which make or break me regardless of the everyday success of my work. Teachers are so petrified of the consequences of having a bad observation that it is common practice to repeat a successful lesson from the previous week. I cannot reconcile myself with letting my students down like this in order to temporarily preserve my career for another three months. As for protection, the culture of fear is endemic: as a newly qualified teacher, it was suggested to me that if I joined a union someone could find a reason to put me on capability procedure.

The fear seems to permeate from above: I've had three head teachers and the thing they've had in common is an inability to change things, as their hands are tied by the same external demands for accountability and good data.

Some didn't hesitate to email late at night or at weekends to say that pencils should not be less than 8cm long. Others made it clear that they didn't want teachers taking work home or coming in at the weekend, but could do nothing to reduce a workload which made doing that a prerequisite of the job. During Ofsted inspections, I have fainted at my desk having worked 42 hours in two and a half days, slept on a colleague's sofa and worn his underwear for two days.

There is a suspicious sense that young teachers are taken advantage of: we are grateful to have a job, and less likely to know or assert our rights. We have fewer family commitments and are generally more physically robust. (I have been told by older teachers who have taught my class that they "couldn't" teach them for more than one day because it was too exhausting.)

Under the current Government and through my training route, Teach First, there has been an increased sense of prestige accompanying teaching as a graduate career, previously only associated with corporate grad schemes. Also seemingly borrowed from the corporate sector, however, is a perverse sense that 'resilience' and a work ethic are the most desirable qualities in new teachers, over empathy, flexible thought, and even being properly qualified, as if a job being punishing is what makes it worth doing.

I've done better than some and have managed three years. But I haven't finished reading more than five books in that time. The habit has been trampled out of me by paperwork and exhaustion. Is that someone you would want teaching your children?

I am a young, energetic person with a first-class degree from a top university. I have been graded an 'outstanding' teacher by colleagues; I like working hard. Really. My grievance has little to do with pay and pensions – for most young teachers, remaining in the profession until pensionable age is a ludicrous prospect, due to unsustainable workload. The only way to do a good job is to work breathless 12-plus-hour days every day, which I cannot keep up. I am not content, however, to work less and do a bad job for the children. I am angry that I am effectively being forced out of a career that I wanted to love.

But at least I wrote all that without mentioning Michael Gove.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks