The year I set up a free school

Michael Gove's big idea is under way. His vision may be different to the ad-hoc classroom Jenny Diski ran in 1970, but it's just as naive, she argues

Karl Marx is, once again, almost right. He just got it the wrong way round in this case. In the matter of free schools history certainly repeats itself, but if the first time was farce, the second looks to me more like tragedy. Anyone under the age of 60, unless they are historians of the middle 20th century, is likely to recognise the phrase "free school" as belonging to the Con-LibDem coalition of 2010. For me, "free school" means something different and long ago.

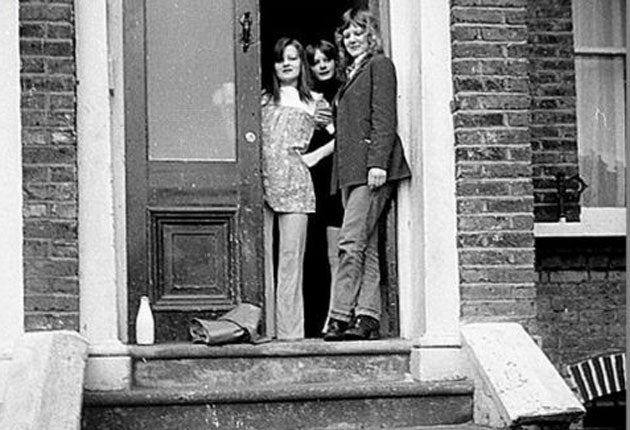

In 1970, with a small group of local people and eventually some money from the local authority (Camden), I started and ran a free school, more by sudden necessity than intent. I'd got to know a handful of children in the area, mostly from a single dysfunctional family. One day their social worker knocked on my door and told me they were all about to be taken into care for persistent truanting. She was talking years of absenteeism and resulting petty crime, rather than a couple of weeks. I'd chatted to them about the idea of free schools, in the air at the time – a network of small groups of adults and children, teaching and learning in a quite different way from the inflexible one-size-fits-all institution that the comprehensive system had become, and that was so unsuitable for difficult children, or children from underprivileged backgrounds. Would I, the social worker said, start a free school for the kids to stop them being taken into care? That was Friday. By Monday, having rung around local people with skills (architects, carpenters, journalists, women at home with children, the unemployed and retired, business people) we'd put together a weekly timetable of lessons, designated my flat as the school house, and were up and running.

We did English lessons (reading newspapers and books, and writing letters to the local council for funding, with a journalist and myself), arithmetic and geometry (with the architect), woodwork (with the carpenter in his workshop), art (piling into the ancient Morris 1000 one of us owned and heading off to art galleries, and looking at buildings around London), history (a politics graduate talking theory and practice, and local older people coming in to tell them about what north London was like and how it had changed), home economics (the kids were given a budget and shopped and cooked for their lunch every day), French and Spanish (any of us who had enough of either language), current affairs (the pupils attended meetings to decide about free school curriculum and organisation), civics (any of us discussing different ways of living in the world that did not involve a lifetime of recidivist crime) and, rather urgently, sex education (anyone who happened to be around, explaining what a bad idea it was to get pregnant and how to avoid it, along with a good deal of discussion on how and why people had sex and how and why it was a good idea to treat people decently whatever you happened to be doing).

We were young, the kids were younger. There was enormous energy because of that and because of the times we lived in. The terminal truants had given up on school, and school had given up on them – when one of the girls was one day persuaded to go back to school by her social worker, she sat through registration, and when her name wasn't even called out, she left. I'd read Ivan Illich's Deschooling Society – misread it, rather – a radically libertarian tract from a Latin American ex-priest who believed that education (like central government, the law and the armed forces) was just another form of power designed to keep people unfree. I didn't, and don't disagree with that. What I saw in his book, rather than his insistence that no one should make it their job to teach anyone anything, was his statement that "Most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting."

I and my fellow free-schoolers believed that the most obdurate children would want to learn, would actually be excited to learn, given a proper, participatory chance in a setting that wasn't inimical to their lives and experience. This was after all the last of the Sixties (albeit in the early Seventies) when learning – reading voraciously, finding things out, grasping new and old ideas – seemed to many of us, along with drugs and sex, the most exciting thing you could do. Certainly we were starry-eyed (as I say, we were young) and what is called "idealistic" (nowadays a derogatory term), and we found ourselves often knocked back by the free school kids failing to get up in time for their lessons, sometimes seeming to refuse to improve their reading skills or getting mystifyingly bored by the materials we offered, but nevertheless, they were often enough engaged in a way they hadn't been previously with their own education, and they wrote effective stories and poetry that expressed their lives and ideas, debated and questioned the obvious, and enjoyed and felt proud of having their own school.

The school lasted several years, but I went on, having finished teacher training, to work in an inner-city comprehensive school in the East End. I confess that I'm not sure that I really taught anyone anything valuable, except once. I was covering a class for an absent teacher of not very intellectually able 13-year-olds. They were doing individual projects, and one of them asked me the name of the woman who had thrown herself under the King's Horse at the races. For the life of me I couldn't recall. "I can't remember. The first name's Emily. Go to the library, find suffragettes in the encyclopaedia, look out for the word Derby." I handed her the word "suffragettes" on a slip of paper. She stared at me astonished, both at my admission of ignorance (teachers aren't supposed to do that) and at being sent off to find out for herself. She returned 20 minutes later, a piece of paper in her hand and her face lit up with pleasure. "Emily Davison," she told me and the rest of the class, added details she'd discovered, pumped up with her triumph. I don't know if she defined the satisfaction she felt, but I knew it was what everyone feels when they find something they are looking for – one of the great delights of knowing how to learn and think for oneself.

Is this any part of what education minister Michael Gove has in mind when he talks about his vision of Free Schools and "outstanding" schools becoming academies? Actually, I haven't heard him talk in terms of pleasure, delight in learning or even anything at all about children and teachers interacting, only about governors and parents taking control in terms of curriculum, discipline and exam results. Writer and Conservative, Toby Young, is in the process with several hundred other parents of setting up a free school. The idea (as with academy schools) is to wrench control from local authorities, to get funding directly from central government, independently to make decisions about how money is spent, and to have control over the curriculum. But even supposing that parents really do know what is educationally best, this is not hands-on teaching. Parents are not expected to run schools and teach lessons. Those responsibilities will be subcontracted to "educational providers". Michael Gove has said he has "no ideological objection" to businesses seeking profits from these new free schools and academies. We might well be looking at schools set up, or de-coupled from local authority oversight by school governors, (who in the case of academies are not legally required to consult teachers or parents) and run by profit-seeking companies. The fear that such schools will be set up and driven by a privileged social group, and that the remaining locally funded schools will have to compete for the most able pupils and finance, doesn't look unreasonable. Free schools and academies are allowed to pay teachers and heads more than the standard tariff and it is likely that most of these schools will be set up in areas of more rather than less privilege.

It seems, actually, already to be the case, as the Sutton Trust – an organisation concerned with promoting social equality in education – has discovered that only 9.4 per cent of children in the "outstanding" schools which are likely to become academies are entitled to free school meals (an indicator of social class) compared to a figure of 15.4 per cent generally across British schools. Funds for setting up these new schools will initially come from the technology budget for existing schools (and a leaked memo shows that Gove and his ministers considered using money currently allocated for free school dinners, although the idea was rejected). After that, it is not clear where the capital costs will come from. The New School Network which has been awarded the job of assisting groups with their applications (and is headed by Michael Gove's previous deputy) says: "The New Schools Network is an independent charity which believes that where parents cannot access a good local state school, groups of teachers, charities, parents and other organisations should be able to set up state schools offering what parents want." But this involves enormous capital expenditure and the withdrawing of pupils when surely improving the existing local schools would be far cheaper and less divisive. A proposed loosening of planning regulations for Free School premises means that they could be set up in shops or houses – most of which, I imagine, don't have much in the way of science labs or playgrounds.

The Sutton Trust report adds that the "improved standards" the new academies claim could as well reflect the better general standards of the children's backgrounds and their families' education levels as evidence of better teaching. Toby Young talks about needing strict discipline in order to learn and it's true that when I spent a week in a local high-achieving school that had taken a nearby "failing" school under its control, I was most struck, not by the quality of teaching (which was dreadfully routine, deadeningly centralised and designed to keep pupils' heads down filling in worksheets), but by the attention to dress codes and a universally enforced punishment system based on numerical values for various offences that added up to a set of incremental discipline procedures. Such schools will be entitled to exclude difficult children who then become an obligation on the local authority, and sent to the already "failing" schools depleted of funding by central government. A worryingly vicious circle.

As to the freedom of curriculum Michael Gove has promised, it's hard to see how a commercial educational provider is going to allow anything other than highly directed teaching where excellence is judged by exam results, not by enthusiastic learners or the numbers of individuals who leave school to find satisfying lives in diverse, interesting and useful ways. And perplexingly, Gove has suggested that Niall Ferguson, an historian keen to reconsider the benefits bestowed on the world by the British Empire, should be in charge of developing the history curriculum. An odd way to keep central government and ideology out of the running of schools. It looks as if the present Government has an even less clear idea of how free schools will actually function than we had in the 1970's.

I took no interest at all in preparing either myself or the children I taught for a financially successful life in a society (that word itself was soon to be dismissed) devoted to economic growth. Had I been trying to predict how the world was going to be, and how therefore people needed to learn to be in it, I couldn't have been more wrong. But I wasn't predicting. I was echoing a preference that some of us had at the time that what is now called quality of life was not dependent on ever-increasing wealth and obvious success. I thought it was important to be able to earn a living that is enough to live on, and if you could do it by doing something you really wanted to do, so much the better. If not, then earn enough to get by and get on with whatever really engaged you. Not especially socialist, actually, a bit individualistic and arty-farty, but there it is. It was my view that our free school kids should have practical skills like getting up in the morning for lessons at a set time because it would be a useful thing to be able to do in order to keep a job. I thought it was a good idea that they should be able to read and write, because they were essential skills for all kinds of life. I had no notion at all of "getting on", rather of getting down to things, learning how to find out what you wanted to learn and then how to learn it. Romantic, idealistic. No preparation at all for today's world, perhaps not for anyone's world. Nevertheless, even now it's a life you can live if you're not too bothered by other people's view of attainment. It's what governments admiringly call a "choice". I wonder if the new Gove free schools and academies will have such a possibility as part of the education they present to children.

The Sixties by Jenny Diski is published in paperback by Profile (£7.99). To order a copy for the special price of £7.50 (free P&P) call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030, or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks