Researchers have a new way to slow memory loss for Alzheimer’s disease

Researchers put mice through water mazes and object recognition tests to see how a drug impacted their brains

New York researchers have taken another step in the lengthy battlle against Alzheimer’s disease, finding a way to slow memory loss and improve learning in mice.

The key is in clearing harmful amyloid beta plaques — or the build up of protein fragments in the brain that are hallmarks of the irreversible and incurable form of dementia that impacts more than 7 million Americans.

The plaques were cleared by using an insulin-regulating protein called PTP1B, which corresponding researcher and professor Nicholas Tonks discovered in 1988. The protein is a recognized target for treating obesity and type 2 diabetes: two risk factors for Alzheimer’s.

The researchers found that giving mice inhibiting drugs resulted in the harmful plaques being removed from their brains.

“The goal is to slow Alzheimer’s progression and improve quality of life of the patients,” Tonks said in a statement.

Mouse maze

It’s unclear how many mice were tested, but all of the subjects were 12-to-13 months old.

The animals were given the inhibitor DPM-1003 at a dose of five milligrams per kilogram of body weight twice a week.

The trial lasted for five weeks, during which the mice underwent a series of tests, including an object recognition test and a water maze.

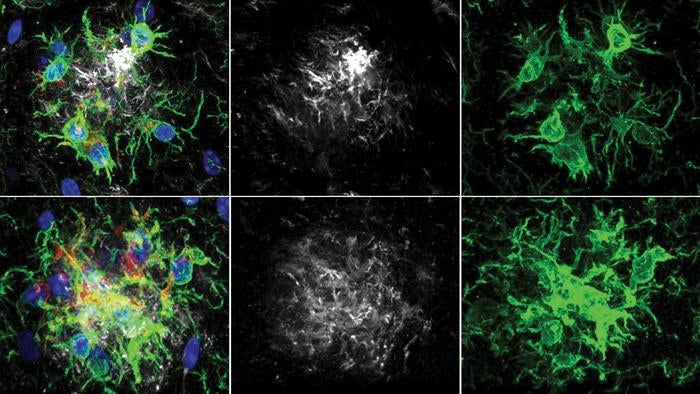

The brains of the mice were then dissected to begin assessing levels of plaques.

A helpful finding

The findings revealed to the researchers how the PTP1B protein in the brain directly interacts with another protein known as spleen tyrosine kinase.

Spleen tyrosine kinase normally regulates the brain’s immune cells to clear out debris, like excess plaques.

“Over the course of the disease, these cells become exhausted and less effective,” graduate student Yuxin Cen explained.

“Our results suggest that PTP1B inhibition can improve [brain immune cell] function, clearing up amyloid beta plaques.”

A hopeful future

Tonks and his team are working with the pharmaceutical company DepYmed, Inc. to develop inhibitors.

He said that existing therapies for Alzheimer’s could be paired with the drugs.

The need for additional treatments is great, with cases of Alzheimer’s expected to nearly double by 2050.

“It’s a slow bereavement,” Tonks, whose mother lived with Alzheimer’s, recalled. “You lose the person piece by piece.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks