Cancer treatment could be revolutionised by targeting a single cell, scientists say

By targeting the stem cell, cancer could be treated like a manageable chronic disease, says Michael P Lisanti

Cancer remains a frightening and largely incurable disease.

The toxic side effects of chemotherapy and radiation make the cure often seem as bad as the ailment, and there is also the threat of recurrence and tumour spread.

Cancer treatment still follows a practically medieval method of cut, burn or poison. If the growth can’t be cut out through surgery, it may be burnt away with radiation or poisoned by chemotherapy.

As a result, cancer therapy remains a daunting diagnosis for patients and treatment options seem limited for a disease which causes one in six deaths globally.

The failure to innovate in cancer treatment may lie in the very poor success rate of clinical trials. Approximately 95-98 per cent of new anti-cancer drugs actually fail phase-III clinical trials, the phase in which new treatments are compared with existing therapy options. This is a staggering statistic. No other business could possibly survive with such an abysmal success rate.

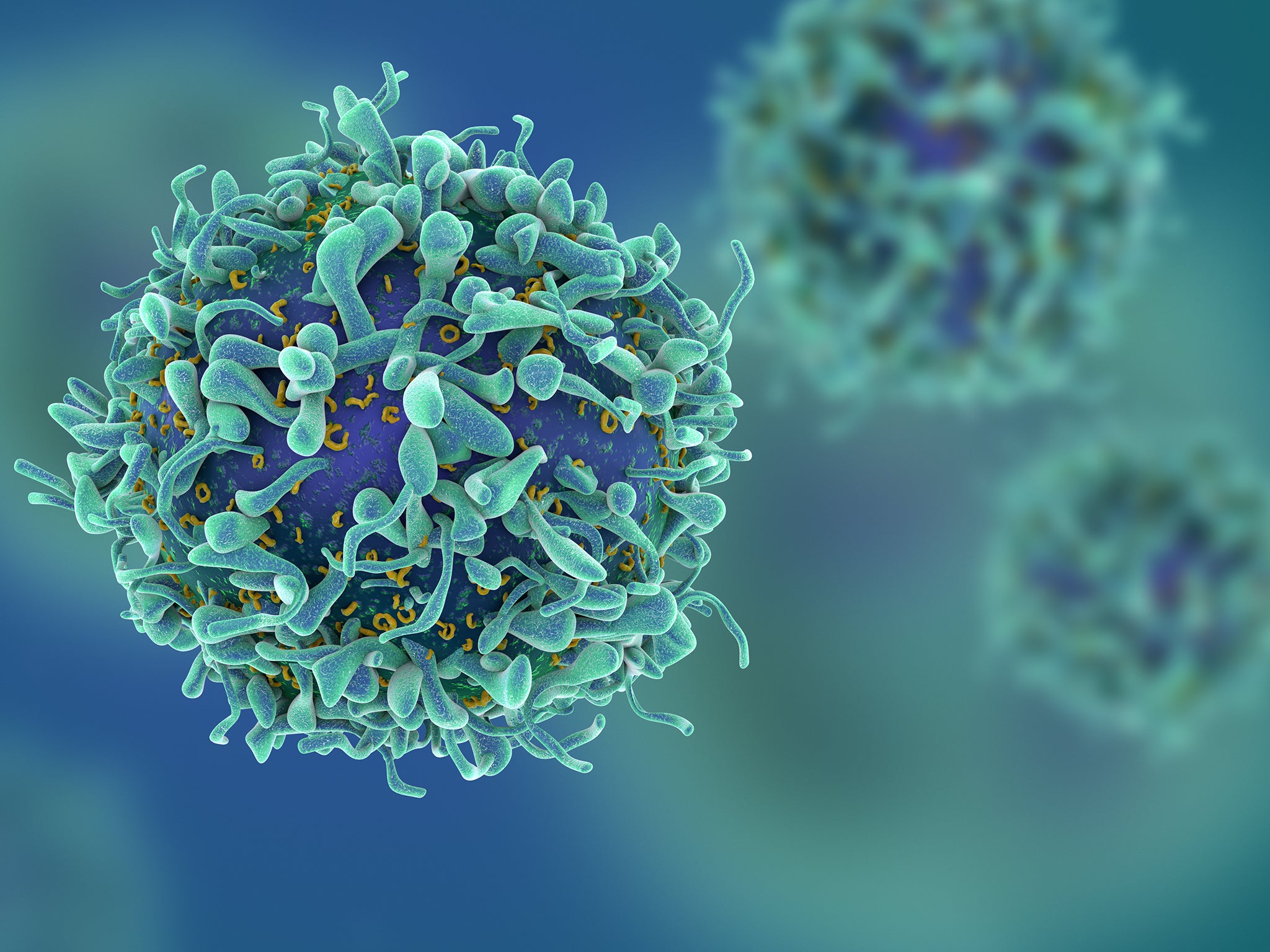

Most drugs are made to target “bulk” cancer cells, but not the root cause: the cancer stem cell. Cancer stem cells, also known as “tumour-initiating cells”, are the only cells in the tumour that can make a new tumour. New therapies that specifically target and eradicate these cancer stem cells are needed to prevent tumours growing and spreading, but for that there needs to be more clarity around the target.

Our new research may have discovered such a target. We have identified and isolated cells within different cancerous growths which we call the “cell of origin”. Our experiments on cancer cells derived from a human breast tumour found that stem cells – representing 0.2 per cent of the cancer cell population – have special characteristics.

They generate vast amounts of energy and proliferate rapidly. We believe that they resemble the cancer cell of origin that has escaped senescence – the natural process of cell ageing and “death” which concludes a healthy cell life cycle. These are thought to be the first cancer cells which start the process of uncontrolled cell multiplication and cause tumours to form.

These cancer stem cells undergo anchorage-independent growth, also known as growth in suspension, without any tissue attachment. This is how metastasis occurs – spreading via the blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. These features put them front and centre as a new target for anti-cancer therapy.

With astonishing luck, these energetic cancer stem cells are colour-coded which means they have a natural phosphorescent glow, making them easy to identify and target.

Now that we have found them and we know how they behave, it should be relatively simple to find drugs to target cancer stem cells. In our new paper we have already shown that they are easily targeted with a mitochondrial inhibitor or a cell cycle inhibitor such as Ribociclib, an FDA-approved drug in the US which would prevent their proliferation.

Ultimately, this means that if we focus on energetic cancer stem cells, we may be able to directly hit the target. We might be able to turn cancer into a manageable chronic disease, like diabetes. We believe that we have arrived at the start of a new, more fruitful, road in cancer therapy. As a consequence, “big pharma” drug screening should actually focus on cancer stem cells and their relevant targets.

Michael P Lisanti is a professor of translational medicine at the University of Salford. This article originally appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks