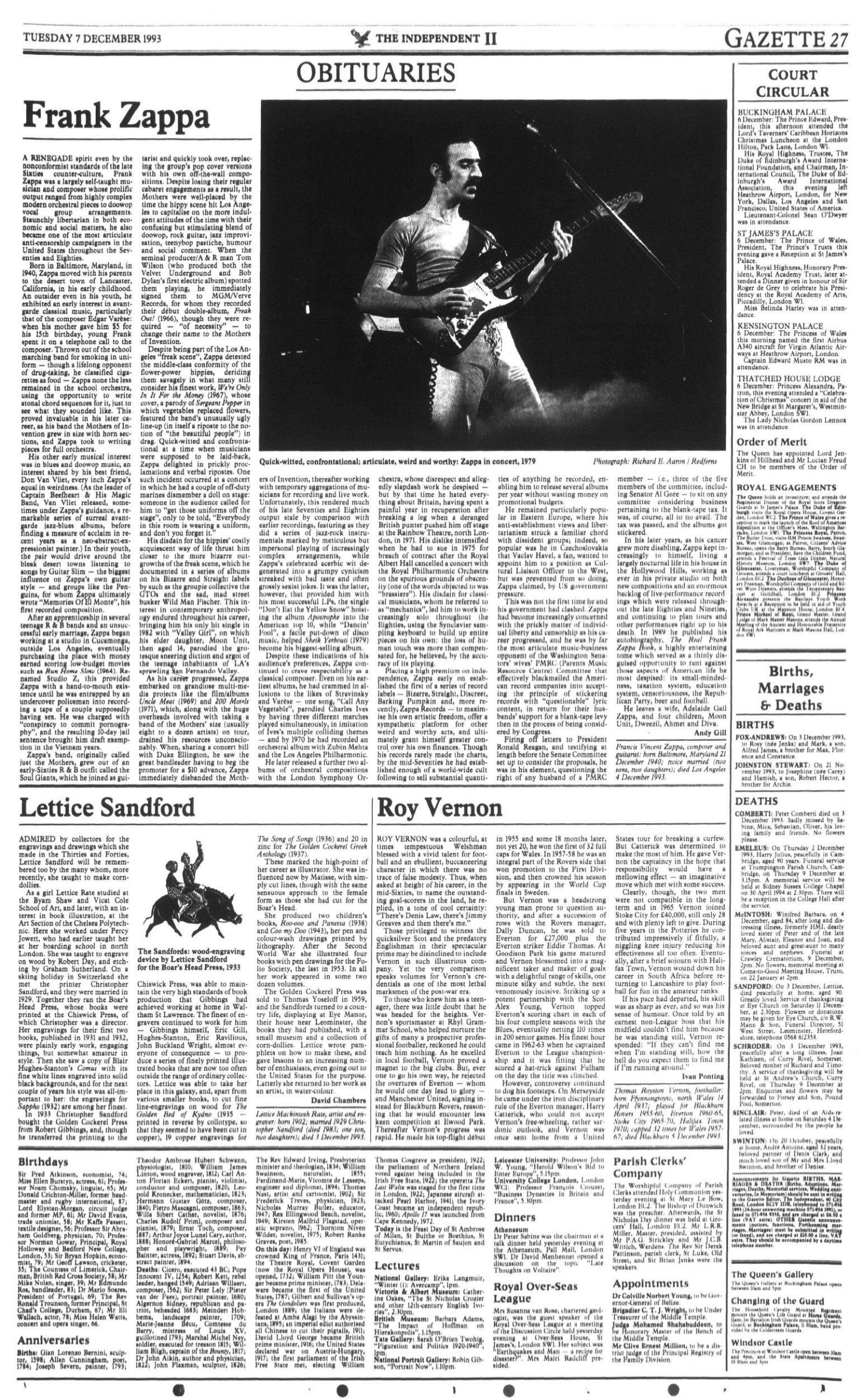

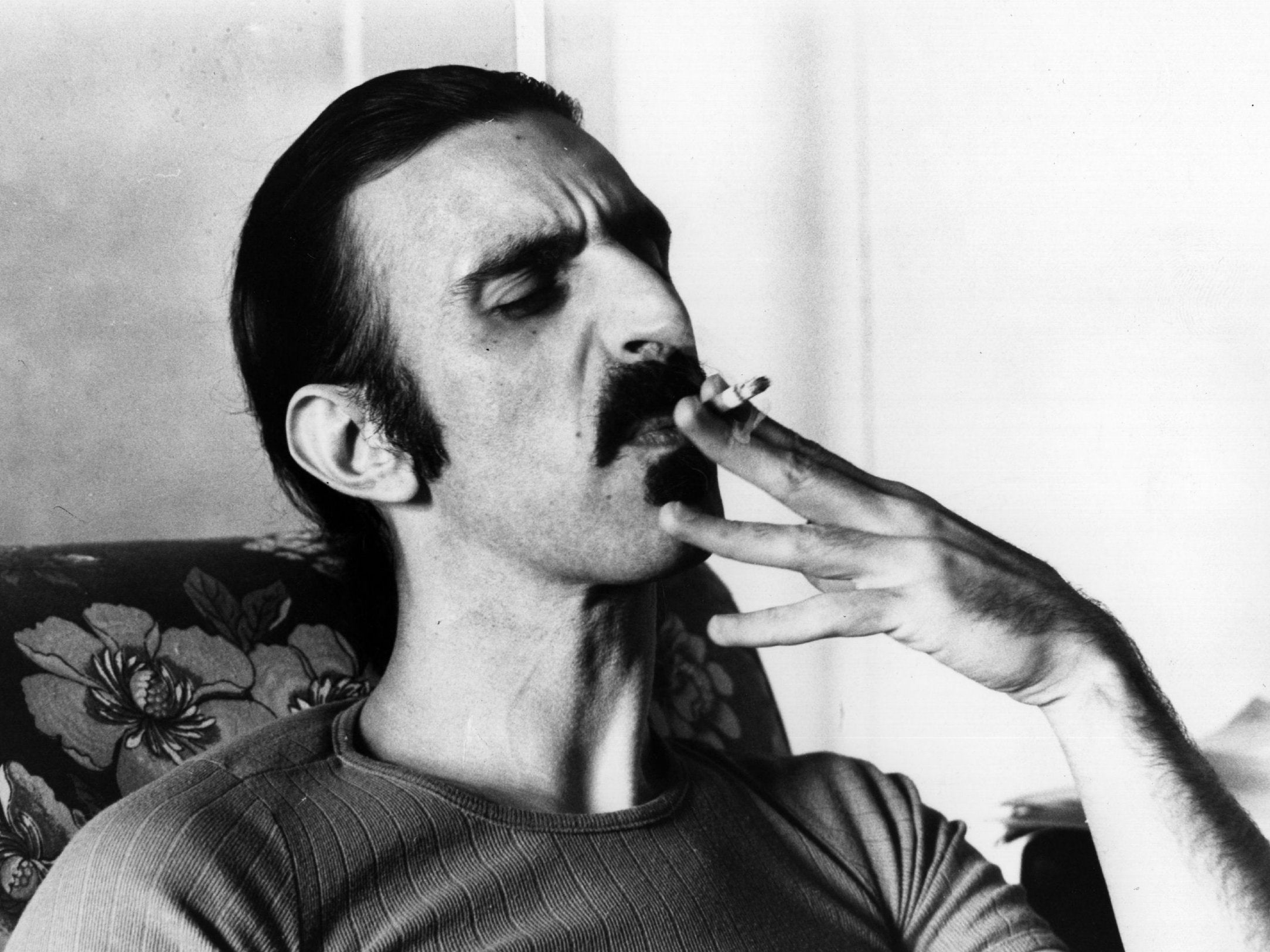

A Life in Focus: Frank Zappa, genre-defying musician who was the epitome of noncomformity

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Frank Zappa, from 7 December 1993

A renegade spirit even by the nonconformist standards of the late Sixties counter-culture, Frank Zappa was a largely self-taught musician and composer whose prolific output ranged from highly complex modern orchestral pieces to doowop vocal group arrangements. Staunchly libertarian in both economic and social matters, he also became one of the most articulate anti-censorship campaigners in the United States throughout the Seventies and Eighties.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1940, Zappa moved with his parents to the desert town of Lancaster, California, in his early childhood. An outsider even in his youth, he exhibited an early interest in avant-garde classical music, particularly that of the composer Edgar Varese: when his mother gave him $5 for his 15th birthday, young Frank spent it on a telephone call to the composer. Thrown out of the school marching band for smoking in uniform – though a lifelong opponent of drug-taking, he classified cigarettes as food – Zappa nonetheless remained in the school orchestra, using the opportunity to write atonal chord sequences for it, just to see what they sounded like. This proved invaluable in his later career, as his band the Mothers of Invention grew in size with horn sections, and Zappa took to writing pieces for full orchestra.

His other early musical interest was in blues and doowop music, an interest shared by his best friend, Don Van Vliet, every inch Zappa’s equal in weirdness. (As the leader of Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, Van Vliet released, sometimes under Zappa’s guidance, a remarkable series of surreal avant-garde jazz-blues albums, before finding a measure of acclaim in recent years as a neo-abstract-expressionist painter.) In their youth, the pair would drive around the bleak desert towns listening to songs by Guitar Slim – the biggest influence on Zappa’s own guitar style – and groups like the Penguins, for whom Zappa ultimately wrote “Memories Of El Monte”, his first recorded composition.

After an apprenticeship in several teenage R&B bands and an unsuccessful early marriage, Zappa began working at a studio in Cucamonga, outside Los Angeles, eventually purchasing the place with money earned scoring low-budget movies such as Run Home Slow (1964). Renamed Studio Z, this provided Zappa with a hand-to-mouth existence until he was entrapped by an undercover policeman into recording a tape of a couple supposedly having sex. He was charged with “conspiracy to commit pornography”, and the resulting 10-day jail sentence brought him draft exemption in the Vietnam years.

Zappa’s band, originally called just the Mothers, grew out of an early-Sixties R&B outfit called the Soul Giants, which he joined as guitarist and quickly took over, replacing the group’s pop cover versions with his own off-the-wall compositions. Despite losing their regular cabaret engagements as a result, the Mothers were well placed by the time the hippy scene hit Los Angeles to capitalise on the more indulgent attitudes of the time with their confusing but stimulating blend of doowop, rock guitar, jazz improvisation, teenybop pastiche, humour and social comment. When the seminal producer/A&R man Tom Wilson (who produced both the Velvet Underground and Bob Dylan’s first electric album) spotted them playing, he immediately signed them to MGM/Verve Records, for whom they recorded their debut double-album, Freak Out! (1966), though they were required – “of necessity” – to change their name to the Mothers of Invention.

Despite being part of the Los Angeles “freak scene”, Zappa detested the middle-class conformity of the flower-power hippies, deriding them savagely in what many still consider his finest work, We’re Only in It for the Money (1967), whose [intended] cover, a parody of Sergeant Pepper in which vegetables replaced flowers, featured the band’s unusually ugly line-up (in itself a riposte to the notion of “the beautiful people”) in drag. [Fear of legal action led to the record company placing the parody cover as interior artwork, and the intended interior artwork as the main sleeve, much to Zappa’s disgust.]

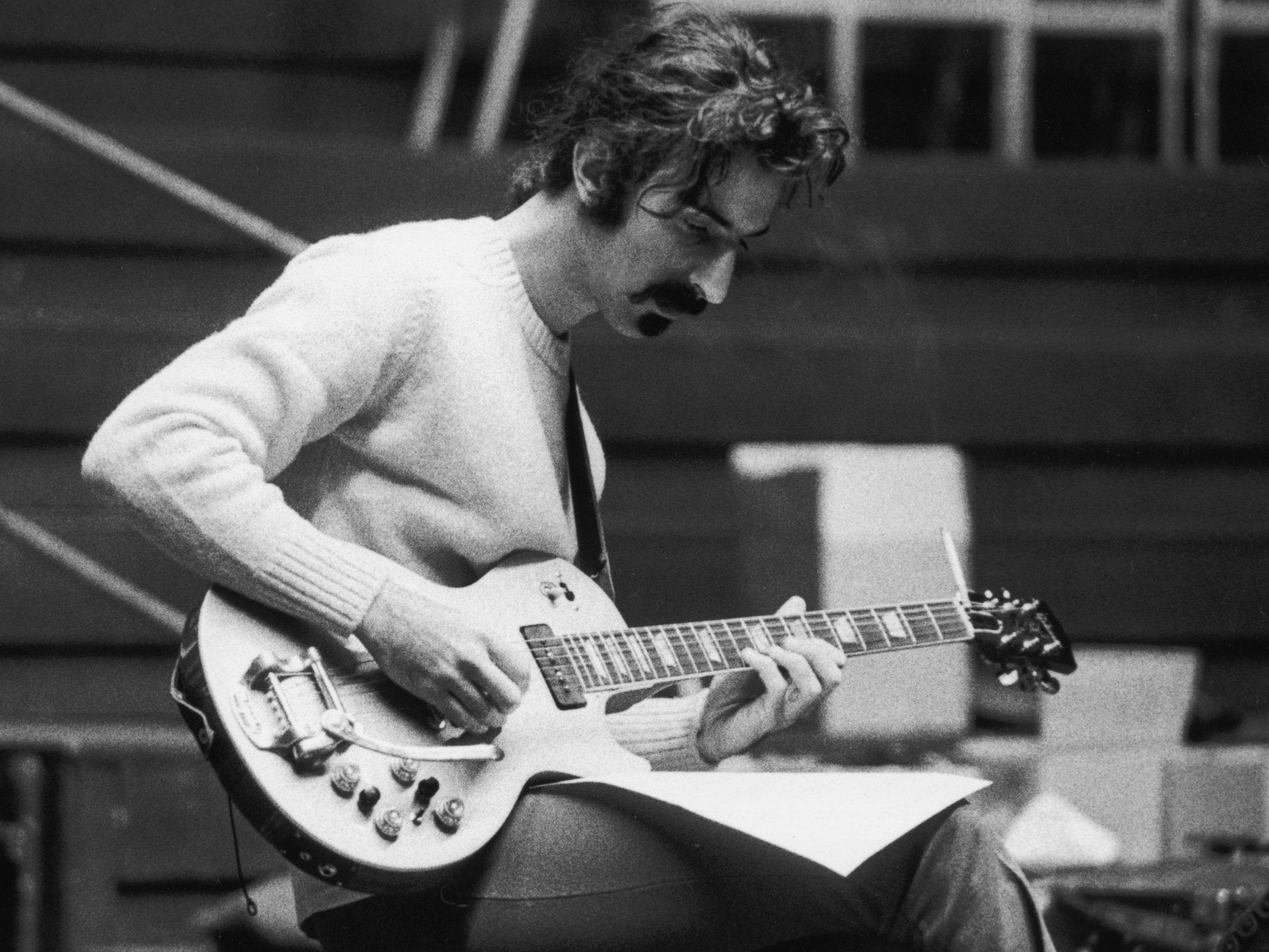

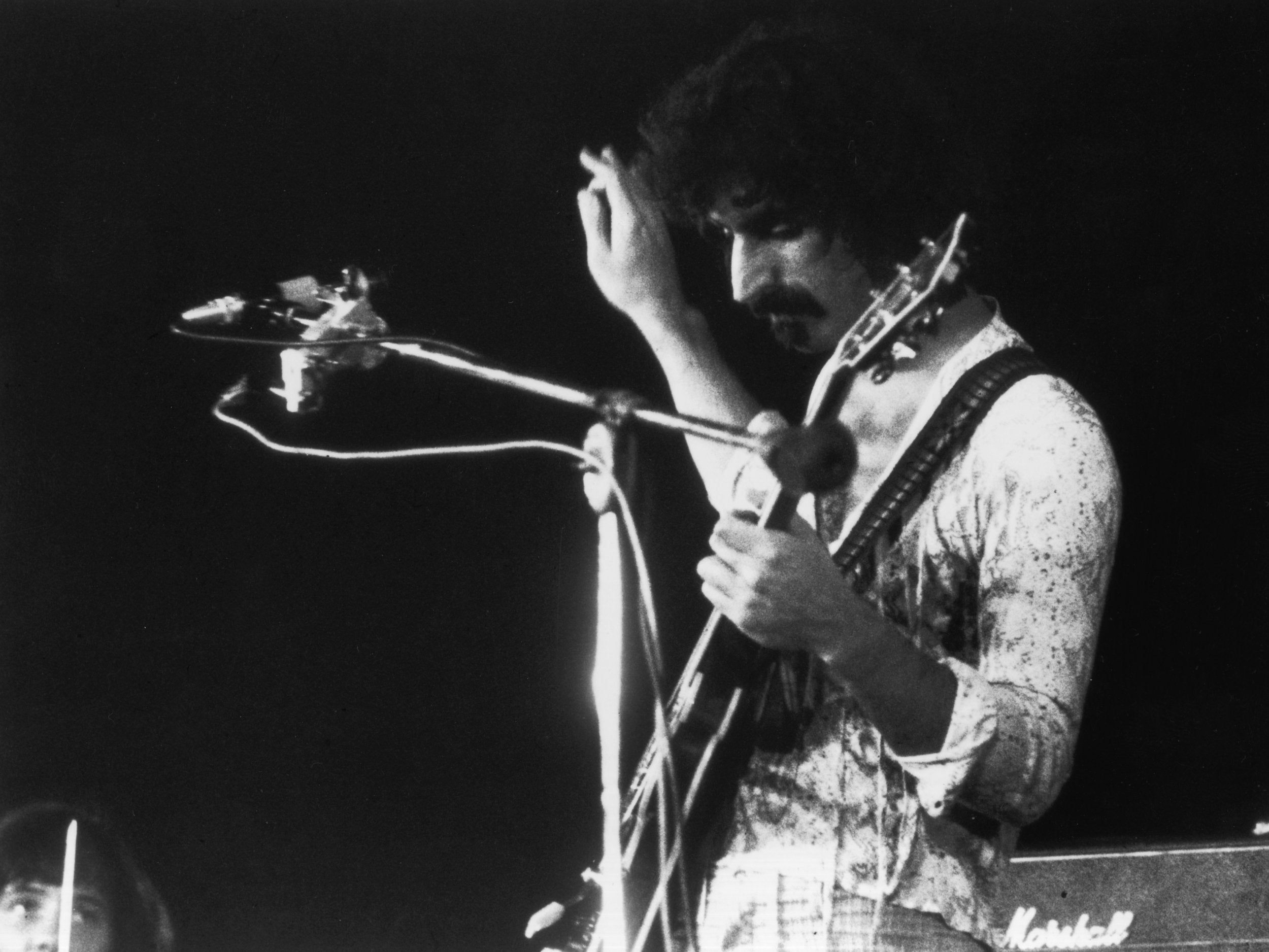

Quick-witted and confrontational at a time when musicians were supposed to be laidback, Zappa delighted in prickly proclamations and verbal ripostes. One such incident occurred at a concert in which he had a couple of off-duty marines dismember a doll on stage: someone in the audience called for him to “get those uniforms off the stage”, only to be told, “Everybody in this room is wearing a uniform, and don’t you forget it.”

His disdain for the hippies’ cosily acquiescent way of life thrust him closer to the more bizarre outgrowths of the freak scene, which he documented in a series of albums on his Bizarre and Straight labels by such as the groupie collective the GTOs and the sad, mad street busker Wild Man Fischer. This interest in contemporary anthropology endured throughout his career, bringing him his only hit single in 1982 with “Valley Girl”, on which his elder daughter, Moon Unit, then aged 14, parodied the grotesque sneering diction and argot of the teenage inhabitants of LA’s sprawling San Fernando Valley.

As his career progressed, Zappa embarked on grandiose multimedia projects like the film/albums Uncle Meat (1969) and 200 Motels (1971), which, along with the huge overheads involved with taking a band of the Mothers’ size (usually eight to a dozen artists) on tour, drained his resources unconscionably. When, sharing a concert bill with Duke Ellington, he saw the great bandleader having to beg the promoter for a $10 advance, Zappa immediately disbanded the Mothers of Invention, thereafter working with temporary aggregations of musicians for recording and live work. Unfortunately, this rendered much of his late Seventies and Eighties output stale by comparison with earlier recordings, featuring as they did a series of jazz-rock instrumentals marked by meticulous but impersonal playing of increasingly complex arrangements, while Zappa’s celebrated acerbic wit degenerated into a grumpy cynicism streaked with bad taste and often grossly sexist jokes. It was the latter, however, that provided him with his most successful LPs, the single “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow” hoisting the album Apostrophe into the American Top 10, while “Dancin’ Fool”, a facile put-down of disco music, helped Sheik Yerbouti (1979) become his biggest-selling album.

Despite these indications of his audience’s preferences, Zappa continued to crave respectability as a classical composer. Even on his earliest albums, he had crammed in allusions to the likes of Stravinsky and Varese – one song, “Call Any Vegetable”, parodied Charles Ives by having three different marches played simultaneously, in imitation of Ives’s multiple colliding themes – and by 1970 he had recorded an orchestral album with Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

He later released a further two albums of orchestral compositions with the London Symphony Orchestra, whose disrespect and allegedly slapdash work he despised – but by that time he hated everything about Britain, having spent a painful year in recuperation after breaking a leg when a deranged British punter pushed him off stage at the Rainbow Theatre, north London, in 1971. His dislike intensified when he had to sue in 1975 for breach of contract after the Royal Albert Hall cancelled a concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on the spurious grounds of obscenity (one of the words objected to was “brassiere”). His disdain for classical musicians, whom he referred to as “mechanics”, led him to work increasingly solo throughout the Eighties, using the Synclavier sampling keyboard to build up entire pieces on his own: the loss of human touch was more than compensated for, he believed, by the accuracy of its playing.

Placing a high premium on independence, Zappa early on established the first of a series of record labels – Bizarre, Straight, Discreet, Barking Pumpkin and, more recently, Zappa Records – to maximise his own artistic freedom, offer a sympathetic platform for other weird and worthy acts, and ultimately grant himself greater control over his own finances. Though his records rarely made the charts, by the mid-Seventies he had established enough of a worldwide cult following to sell substantial quantities of anything he recorded, enabling him to release several albums per year without wasting money on promotional budgets.

He remained particularly popular in eastern Europe, where his anti-establishment views and libertarianism struck a familiar chord with dissident groups; indeed, so popular was he in Czechoslovakia that Vaclav Havel, a fan, wanted to appoint him to a position as cultural liaison officer to the west, but was prevented from so doing, Zappa claimed, by US government pressure.

This was not the first time he and his government had clashed. Zappa had become increasingly concerned with the prickly matter of individual liberty and censorship as his career progressed, and he was by far the most articulate music-business opponent of the Washington senators’ wives’ PMRC (Parents Music Resource Centre) Committee that effectively blackmailed the American record companies into accepting the principle of stickering records with “questionable” lyric content, in return for their husbands’ support for a blank-tape levy then in the process of being considered by congress.

Firing off letters to President Ronald Reagan, and testifying at length before the Senate Committee set up to consider the proposals, he was in his element, questioning the right of any husband of a PMRC member – ie, three of the five members of the committee, including Senator Al Gore – to sit on any committee considering business pertaining to the blank-tape tax. It was, of course, all to no avail. The tax was passed, and the albums got stickered.

In his later years, as his cancer grew more disabling, Zappa kept increasingly to himself, living a largely nocturnal life in his house in the Hollywood Hills, working as ever in his private studio on both new compositions and an enormous backlog of live-performance recordings which were released throughout the late Eighties and Nineties, and continuing to plan tours and other performances right up to his death. In 1989 he published his autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa Book, a highly entertaining tome which served as a thinly disguised opportunity to rant against those aspects of American life he most despised: its small-mindedness, taxation system, education system, censoriousness, the Republican Party, beer and football.

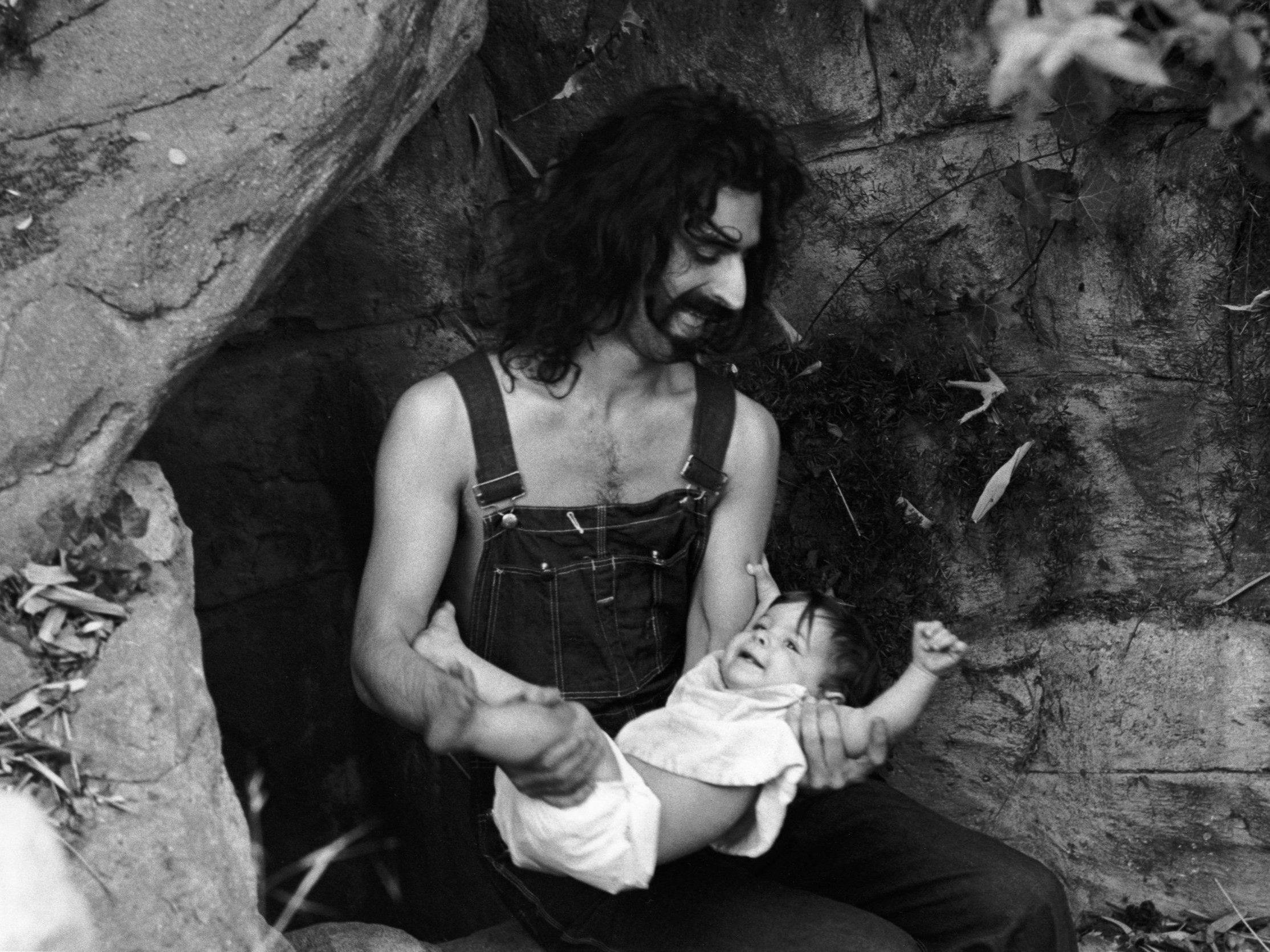

He leaves a wife, Adelaide Gail Zappa, and four children, Moon Unit, Dweezil, Ahmet and Diva.

Francis Vincent Zappa, composer and guitarist, born 21 December 1940, died 4 December 1993

Adelaide Gail Zappa died 7 October 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks