Agatha Christie: Why we still love her 'cosy crime' novels

This year is a bumper one for adaptations of Agatha Christie’s works. On what would have been the 127th birthday of the queen of crime, David Barnett investigates

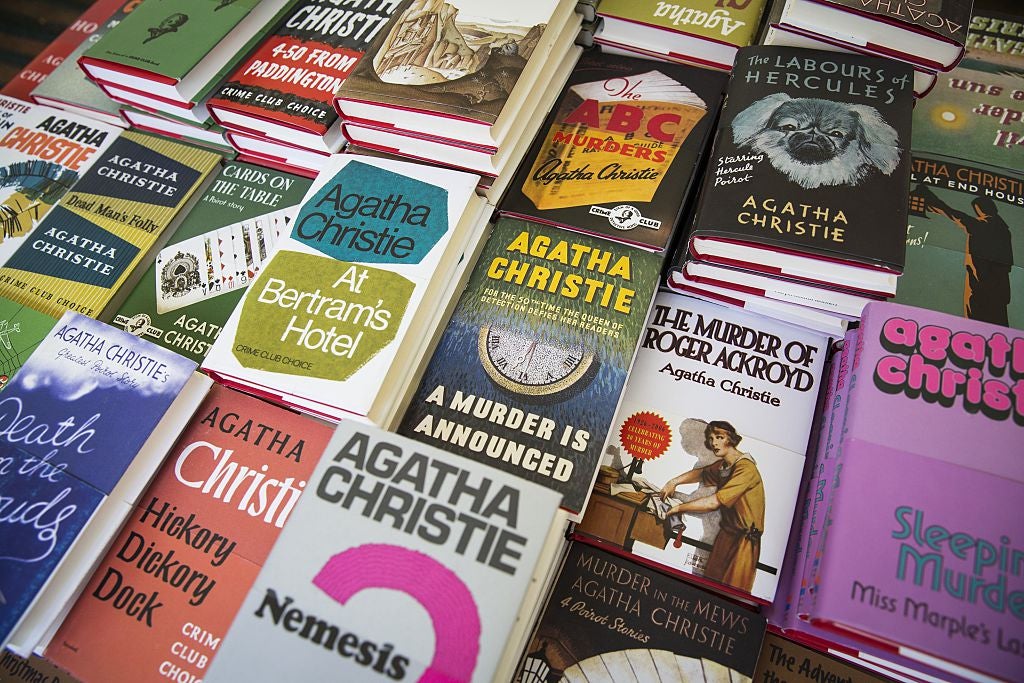

Everyone knows Agatha Christie, or at least, we think we do. If we haven’t perhaps read as much of the output of the archetypal British mystery writer as we should have done, we’re familiar with her work through the dozens of screen adaptations of her timeless whodunnits.

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, also Lady Mallowan, also Mary Westmacott, the name under which she wrote a clutch of romance novels, was born on this day in 1890. Her work has become synonymous with the trope of the country house mystery, the landed gentry and Jazz Age good-time boys and girls whose ordered, privileged world is suddenly thrown into disarray by the fly in the ointment of a rather awkward corpse found in the library, or on the croquet lawn.

Agatha Christie spawned a sub-genre of crime, commonly called today “cosy crime”, and her children can be found in everything from Murder, She Wrote to Midsomer Murders to Death In Paradise, where a dead body is a puzzle, an enigma, a knot just waiting for a clever sleuth to come along and unravel it and save the day.

And that’s often what we think of when we think of Agatha Christie, a game of Cluedo brought to life, death a mere inconvenience for the living… and the way to root out a cunning murderer who’s covered their tracks just insufficiently to properly put off a gutsy Miss Marple or thoughtful Hercule Poirot off the scent.

Just don’t say that to James Prichard. He is the chairman and CEO of Agatha Christie Ltd, the body set up to manage the queen of crime’s literary estate and also to license her works for adaptation. He’s also the great grandson of the woman himself, so knows whereof he speaks.

“It’s one of my pet hates when people use the term ‘cosy crime’,” says Prichard. “Agatha didn’t think murder was in any way cosy. She is often quite underrated regarding her stories and characters. She wrote about people, and the effects that murder had upon them.”

Prichard and his team are the custodians of Agatha’s legacy and carefully choose the projects that will come to fruition based on her work from among the many requests they get. The final quarter of 2017 is something of a bumper period with the latest of the BBC’s excellent Sarah Phelps-penned adaptations, Ordeal by Innocence, a highlight of the Christmas schedules.

Before that, in November, we get a star-studded – perhaps the most starry ever – cinematic adaptation of her classic Poirot novel Murder on the Orient Express. With Kenneth Branagh directing and taking the role of the shrewd Belgian sleuth, the movie also features a cast list to drool over. Johnny Depp, Judi Dench, Michelle Pfeiffer, Daisy Ridley, Derek Jacobi, Penelope Cruz, Willem Dafoe, Olivia Coleman… there’s barely a buffet car waiter in this movie who doesn’t have a CV as long as your arm.

It’s perhaps a story we think we are all familiar with. But perhaps think again. A question for you: in Murder on the Orient Express, whodunnit? Can you remember? If you can’t you’re not alone.

Fox, who is behind the new adaptation, did a little bit of market research which found that around 90 per cent of those surveyed who thought they fully remembered Murder on the Orient Express couldn’t actually remember the ending too well. Which is perhaps not hugely surprising; unless you’re a Christie connoisseur who’s read all the books, you might only have seen the film or TV adaptations. You’ll remember the big one, of course, with Albert Finney as Poirot and among the suspect list Sean Connery, Ingrid Bergman, Lauren Bacall, Vanessa Redgrave, John Gielgud. But that was made in 1974, and Branagh’s take on it is the first big screen outing for the story since then.

“It’s more than 40 years since the last adaptation of this book, and that can surprise some people,” says Prichard. “Obviously, we would like it if everyone was very familiar with my great grandmother’s books, but that is not always the case, especially in the United States. This is an extraordinary adaptation and along with the BBC’s Ordeal by Innocence in December, our star is very much in the ascendency at the moment.”

Murder on the Orient Express will mark almost 90 years of Agatha Christie adaptations. The very first one was in 1928, when the film industry was really in its infancy, and only eight years after Agatha’s first published novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. That first movie was The Passing of Mr Quin, based on one of her short stories. Don’t worry if you haven’t seen it, there’s probably nobody alive that has. The prints of it have long been lost to history, and nothing remains of it.

Between that film and the forthcoming Murder on the Orient Express, there have been more than 65 main adaptations on TV and film, not counting the various TV series featuring perennial favourites Miss Marple and Poirot. But what is it about Agatha’s work that is so eminently adaptable?

Mark Aldridge is the author of Agatha Christie on Screen, published late last year by Palgrave Macmillan, and he says her appeal is twofold. “The main reason, of course, is that they’re just really good stories,” he says. “There’s no getting away from that. It’s sometime too easy to underestimate just how brilliant her plotting is. On a superficial level, people know what they’re going to get with a Christie adaptation. You know it’s going to make sense at the end, that the audience is not going to feel put out or cheated.

“But the other aspect is that there’s a deep psychological level to Christie’s work. You can watch a film of her work purely for the plot, but you can also watch it for insights into the characters and the human conditions. She was a great observer of people and often put traits of people she knew into her characters.”

There’s something about Agatha’s work that gives it an enduring appeal. There have been attempts to set her plots in the modern age – there was a fad for it in America in the 1980s – but there’s always a problem with updating crime stories from the Golden Age… once you throw modern technology into the mix, perhaps DNA or mobile phones or CCTV, the plots are sometimes made redundant, the brainpower of the sleuth sidelined.

For Aldridge, the best adaptations are those set in the period in which the books were written. And don’t forget, Agatha wrote from the 1920s to the 1960s, so the world was constantly changing around her, and her stories evolved to match.

“There’s perhaps a sense of nostalgia about her work,” he says. “There’s a part of us that likes to see village greens and country houses, ships steaming up the Nile. Christie was a very visual writer, and she was very well travelled and used a lot of exotic locations she had actually visited.”

For Mark, the best adaptation is Billy Wilder’s 1957 take on The Witness for the Prosecution, which he thinks is a case study in how to adapt Christie. “The basic plot is there but Wilder adds something of himself to it, there’s some comedy, and that elevates it from being a standard murder mystery.”

But, he says, Christie was never too enamoured with any adaptations of her work. She fancied herself as a screenwriter and wrote a script for an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, but it was never made. And although she had no personal beef with Margaret Rutherford, who played Miss Marple in a series of films in the 1960s, she reportedly hated the movies, says Aldridge.Christie’s own favourite, like his, was the Billy Wilder movie, and she is thought to have approved of the big 1974 adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express, though by then she was 84 and died not long after, in January 1976.

Prichard remembers well his great-grandmother, and the day she died. He was just six, and returned home from school to find his father sitting, unusually for him, in a darkened room, where he broke the news.

“She was very much a part of my life as a small boy,” he remembers. Her relationship with his father was very close. “If there was a prize for Greatest Grandmother of the 20th Century she would have won it. I always remember my dad saying she was a good listener. She was a keen observer of human life and what makes people do extraordinary things.”

And that’s at the crux of Christie’s work. The deaths at the centre of her stories are not just plot devices, not Hitchockian McGuffins to drive the story but with no real substance; they are the very reason for the story, and the things that drive people to murder are what really concerns her.

It is those aspects of Christie’s work that have fascinated screenwriter Sarah Phelps. She has had two adaptations broadcast by the BBC over the last two years; 2015’s And Then There Were None and last year’s The Witness for the Prosecution. In December, making this surely a Christmas tradition, the third Phelps-penned story, Ordeal By Innocence, hits the screens.

Aldridge thinks these adaptations are “brilliant”, and Prichard, as overseer of all Christie adaptations, says, “Since reading Sarah’s scripts even I’ve started looking at the books slightly differently because she brings so much to them.”

In both of these adaptations, the shadow of war hangs blackly over the proceedings, and Phelps has certainly delved deep into the psychological make-up and often morally ambiguous motivations of the characters.

Perhaps surprisingly, given her nuanced and multi-layered treatment of the stories, Phelps is not a long-time Agatha fan – in fact, she hadn’t read the books before embarking on the adaptations.

“I think I benefited from that because it meant I wasn’t too overly-familiar with the stories,” she says. “I had an idea that I thought I knew what they were all about, but that was really informed by snippets of things I’d seen and the layer of familiarity most of us have with her work.

“I suppose I’d always thought of the books as having a parlour game feel to them, quite comforting, murder as a cosy entertainment. So I was genuinely shocked when I read them and discovered how brutal and remorseless they are.”

Phelps brings out in her adaptations what makes the characters tick. “It’s not just a whodunnit, but a whydunnit,” she says. “There are deep, underlying psychological reasons why somebody has been killed, and why somebody has become a killer. It really matters that there’s been a murder, it’s not just a parlour game or plot device. Why has someone been driven to kill another person? What’s the flaw in their personality that’s going to put them in this maelstrom of desire and cruelty?”

Phelps places her adaptations in the period they were written, which she thinks is important to allow the weight of history, and what was happening in the world at the time, to bear down on the story. The Witness for the Prosecution was set in the 1920s, when the First World War still scarred those who had survived it, while And Then There Were None is placed in 1939, with the world on the brink of another global conflict. The forthcoming Ordeal By Innocence is set in the 1950s, when the Cold War provided the backdrop to international affairs.

“I want the adaptations to communicate with each other,” she says, “to build a picture of life in the first half of the 20th century. There was war, recession, questions over cultural identity, and these are things and patterns that are relevant to us today.”

Given Prichard’s enthusiasm over Phelps’s treatment of his great-grandmother’s work, there’s a fair chance that Christie might well finally be getting the adaptations of her work she perhaps never felt she saw in her lifetime. But whatever your view on any adaptation, the original source material is still there, unsullied, for you to discover and cherish.

“The one thing I take away from the BBC adaptations especially,” says Prichard, “is realising once again how well these stories stand up to modern treatments. At the end of the day, they’re bloody good books.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks