How Brexit grew from an awkward encounter on the campaign trail 10 years ago

John Rentoul traces back the UK’s full-blown rejection of the EU to a scorned ‘bigot’ in Rochdale

Gordon Brown had been heckled during a TV interview at an event in Rochdale, a Liberal Democrat seat that Labour was trying to win back in the 2010 election. After the interview, the prime minister’s aides brought Gillian Duffy, the 65-year-old heckler, to meet him. “All these eastern Europeans what are coming in, where are they flocking from?” she asked – although, as they say, it was more of an observation than a question, because it contained its own answer.

Brown was irritated. He thought the encounter had gone badly and the media would make something of it. “That was a disaster,” he said, as he got into his car. He had no idea how right he was about to be. His microphone was still on. “She was just a sort of bigoted woman,” he complained. “She said she used to be Labour. I mean it’s just ridiculous.”

A short while later, Brown was mortified, as the recording of his dismissing a voter as a bigot became headline news. He was pictured with his head in his hands at his next engagement, in a radio studio, and soon he was outside Ms Duffy’s house, trailing TV cameras, describing himself as a “penitent sinner” and begging her to accept his apology.

In the end, Brown’s encounter probably had little effect on the result of the election. Labour won Rochdale – Simon Danczuk became the MP. An MP with a Polish surname, ironically. Nationally, Labour did better than many expected. Brown had been the most unpopular prime minister in opinion-poll history, but he also earned some grudging respect for the way he handled the financial crisis, and was able to deprive David Cameron of his majority.

There was a symmetry between the beginning of the decade and the end of it, with a Lib Dem leader making a decision that would be disastrous for the party. At the beginning, Nick Clegg chose to go into coalition with the Conservatives instead of trying to do a deal with David Miliband as an interim Labour prime minister. At the end of the decade, Jo Swinson gave Boris Johnson the election he wanted and watched in horror as her party lost seats, including her own. At least Clegg got to be deputy prime minister for five years.

Yet Gillian Duffy was trying to say something important – what she was trying to say would take a whole decade to be heard. It was incoherent, which might have been one reason Brown was dismissive. She used to be Labour, she told him. She thought the vulnerable couldn’t get what they deserved, and people who didn’t deserve it seemed able to “claim”. And then she mentioned eastern Europeans, who Brown knew work hard and tend not to claim benefits. But that wasn’t what she was trying to say. I think she was trying to say the country was changing in ways that weakened the sense of belonging, of mutual obligations, of nationhood.

She came back for an encore in the 2016 EU referendum campaign. The BBC interviewed her, and by now the cause of her discontent seemed clearer. “We’re giving all the time, we always put our money in, but we never seem to get anything back to help us,” she said. “I’m frightened of us losing our identity as well. We’ll never get England back to where it was, but I love being English and I don’t want to be a European.”

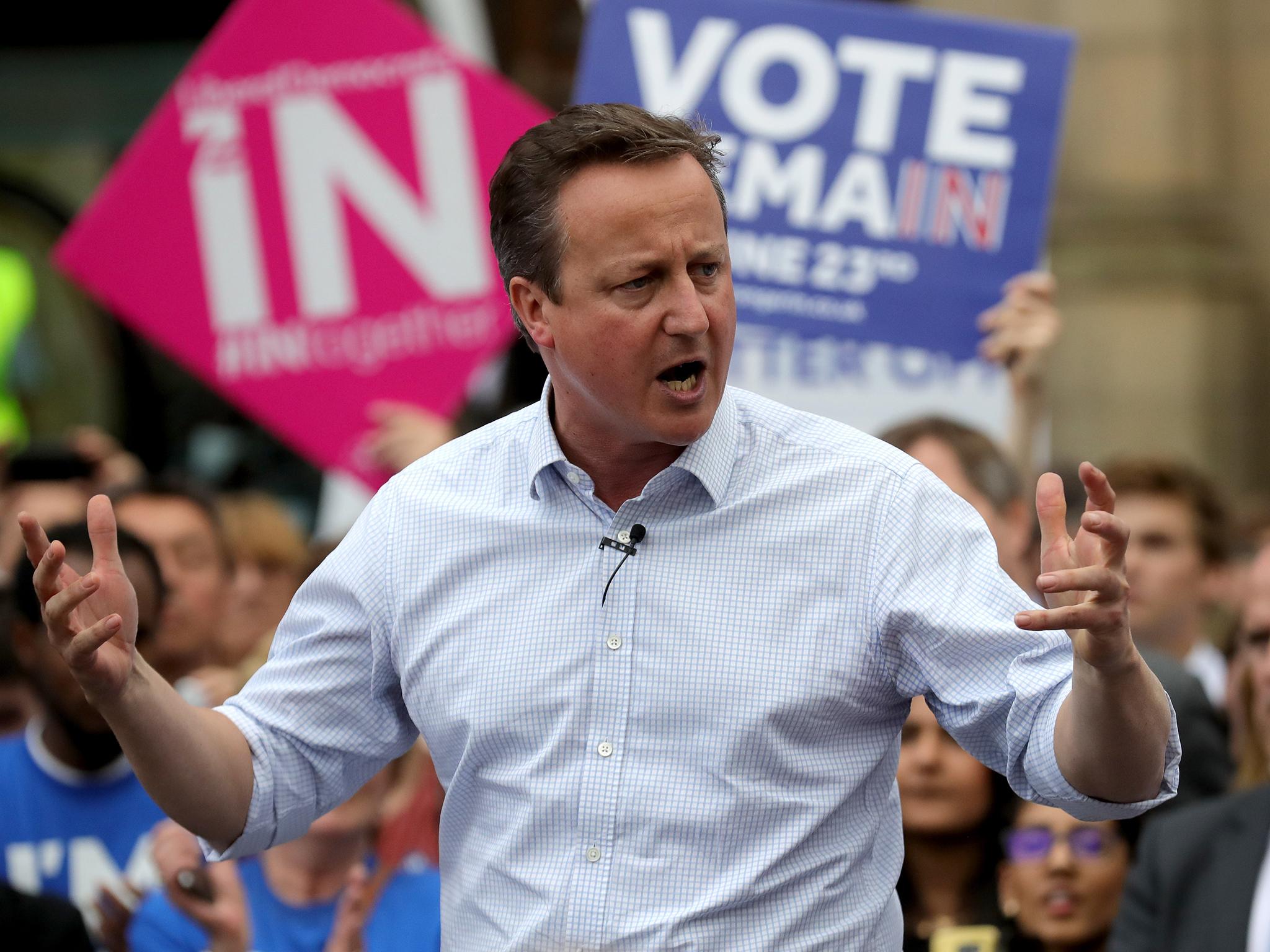

David Cameron hadn’t listened either. In opposition, he had persuaded his party to shut up about Europe, so that he could get on with being an efficient, compassionate prime minister. Dealing with the deficit was an unexpected challenge that required a bit of the fluid opportunism that he thought marked him out for high office. He and George Osborne might have overdone it a bit, but he thought he was good at being prime minister, as he had laughingly said he would be.

There were, however, soon premonitions of another unexpected challenge that would in the end overwhelm him. After a year and a half of successful coalition government with Nick Clegg, Cameron was rocked by what seemed to him a pointless rebellion by 81 Conservative MPs demanding a referendum on Europe.

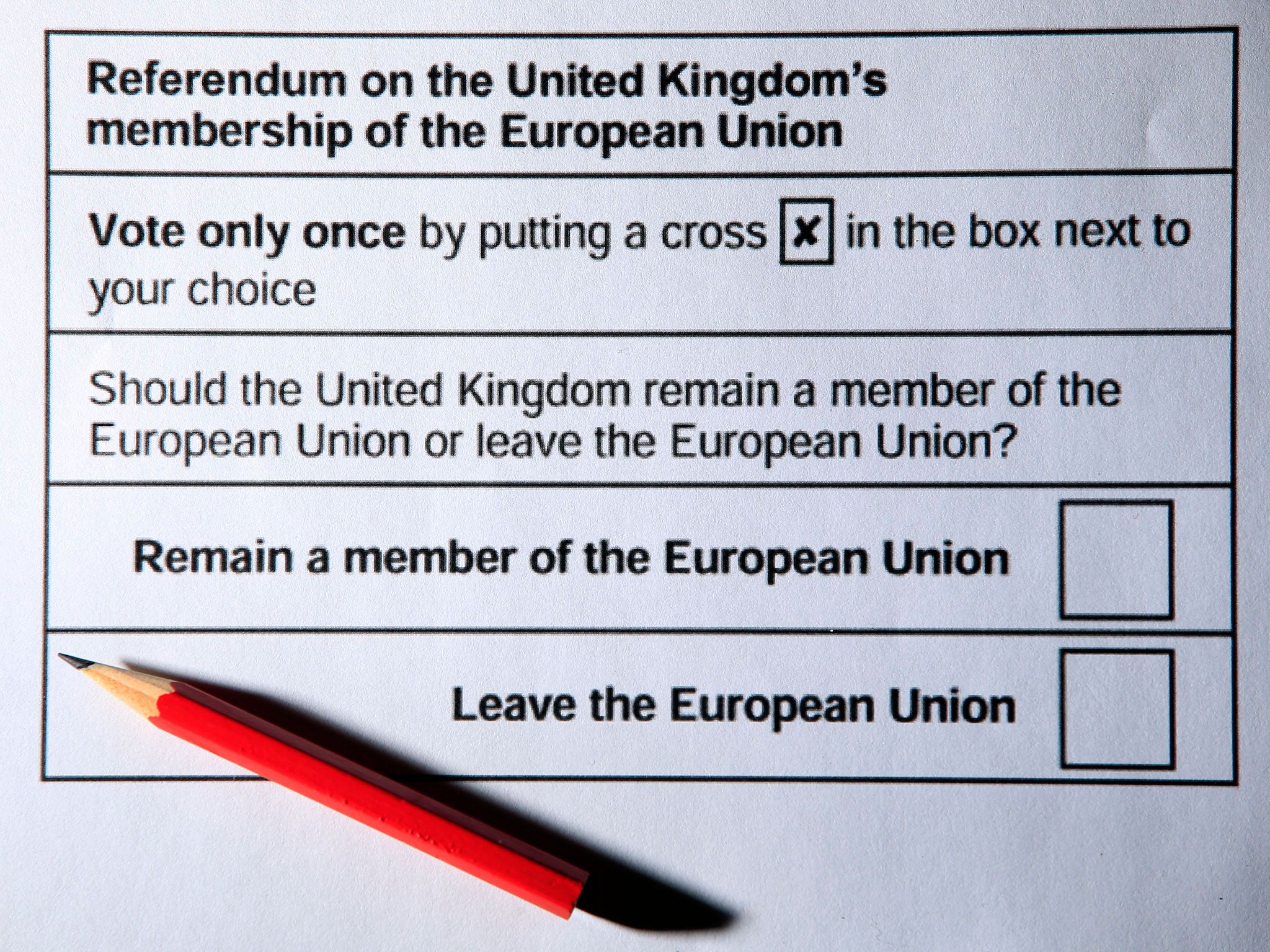

A referendum? On being in or out of the EU? Whatever for? He was used to demands for a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty – indeed, he had made them himself, in opposition. But Brown had signed it and parliament had ratified it before Cameron became prime minister, so that was the end of it. Except it wasn’t. Had Cameron but known it, it was only the beginning.

It is hard now to recall how distant the prospect of leaving the EU seemed in 2010-12. It was outlandish, fruitcake stuff. The UK Independence Party was a fringe outfit. It won 3 per cent of the vote in the 2010 election. It was not even led by Nigel Farage at the time. It fought the election – in nearly every seat in Great Britain – under the nominal leadership of Lord Pearson. Farage had stood down in November 2009, to devote himself to fighting Buckingham, the speaker’s seat. It was a publicity stunt, trying to take advantage of the convention by which the main parties stand aside to allow the speaker to be re-elected. As it was, Farage came third behind John Stevens, a pro-EU former Conservative, who had engaged in a similar and slightly more successful publicity stunt for the other, pro-European, side of the argument.

After the Tory rebellion in November 2011, though, Daniel Finkelstein, the Times columnist, asked: “For how long will it remain the case that questioning Britain’s membership of the EU will be something that cannot be done by a mainstream political figure?” In those days even Bill Cash, the paleosceptic Tory MP, insisted that all he wanted to do was to reform the EU so that it ceased to infringe our sovereignty. That was what Eurosceptic meant in those days. Someone who was against Britain adopting the euro as the currency, which was pretty much everyone after the Labour government decided against it. Someone who was opposed to further EU integration, which the Lisbon Treaty represented, although it was diluted after the original plans for an EU Constitution were defeated. At most, I wrote at the time, there were a dozen Tory MPs who would say publicly that Britain would be “Better Off Out”.

What was intriguing about Finkelstein’s column, however, was that its author was also moonlighting as Cameron’s diary keeper. Every week, he would – we know now – visit the prime minister and record his great thoughts. That means that Cameron, too, must have been pondering when “in or out” was going to become a live question for him.

At the time, millions of Britons like Gillian Duffy were asking of Europe: what is in it for us? The question for politicians at Westminster was whether the euro would survive the debt crisis, and whether Greece would have to abandon the currency. A strange word, Grexit, was invented to describe the possibility not that Greece might leave the EU, but that it might be ejected from the currency union at the EU’s core.

I wrote at the time: “I am often surprised by Labour MPs, especially former ministers, now confiding that they have been Eurosceptics all along, and that they think there will have to be a big adjustment in Britain’s place in Europe. That moment looks as if it will be upon us sooner than they expected.” By Eurosceptic, I clarified that they meant renegotiating the terms of EU membership and staying in the EU.

The arguments over the Lisbon Treaty, and Cameron’s alleged betrayal of the referendum promise on it, had put two ideas into the mainstream: one, that the terms of membership could be revised; two, that a referendum was a way to settle the European question – whatever the question ended up being.

In 2012, a blogger adapted Grexit to the British debate, and coined Brexit. And Ukip, with Nigel Farage back as leader and getting better at publicity-seeking, hit 10 per cent in the opinion polls. All the time, the Conservative Party was in a state of restless ferment. After 2016, Cameron was roundly criticised by Remainers for having promised the referendum in the first place, and accused of doing so purely to manage the divisions in his own party. But the reason his party was becoming hard to manage, and the reason Ukip was a threat, was that public opinion was becoming more and more hostile to EU membership.

From the moment 10 new countries joined the EU in 2004, large numbers of workers came to the UK. Tony Blair’s government had considered imposing a delay before allowing full free movement of people from new member states, but did not think that large numbers would move. When they did, they helped to boost the economy. It was only in this decade that the social and political consequences of that decision worked themselves out.

Trying to impose a simple story on a whole decade, an arbitrary span of years, is bound to be misleading, and it is bound to miss other important stories happening at the same time. But it could be said that the story of the last 10 years is that of Britain’s departure from the EU.

Gillian Duffy was the Everywoman of the decade. She represented the people – or at least the bare majority of them, as it turned out. Remainers are quite right to say that Europe was rarely listed as an important issue in the polls until the referendum; but that was because it never seemed that there was much that could be done about it. People thought immigration was an important issue, and increasingly related it to free movement under EU law. Public opinion was always in favour of less power for the EU, and if the people were asked, from 2010 until 2013, they generally wanted to leave. Indeed, it was only after Cameron promised a referendum, in January 2013, that Remain took the lead.

The promise was no petty decision, taken to try to hold the Tory party together: it was the only way Cameron could hope to win the 2015 election. It seems perverse to blame a politician for responding to the pressures of public opinion in a democracy. The referendum came about because the people wanted it – by definition, from the result – and managed to bend a parliament of Remainers into giving it to them.

That makes Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson the politicians of the decade. At the start of it, Farage was crawling out of the wreckage of a light plane that had been towing a “Vote Ukip” banner, and Johnson was, after a shaky start, the re-electable mayor of a Labour-voting world city humming with the dynamism of immigration, much of it from the rest of the EU.

For most of the past 10 years our leaders were Remainers: David Cameron, Nick Clegg, Theresa May; opposed by Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn, a less decided Remainer. But by the end of the decade, Johnson, who only declared for Leave in February 2016, after Cameron failed to renegotiate the terms of UK membership, emerged triumphant.

Only he could finally defeat Farage, who re-entered the fray after May failed to meet the original deadline for Brexit. Only Johnson could force Farage to pave the way, by standing down half his candidates, for the election of a Conservative government that would finally take Britain out. Farage tried to take credit for Johnson’s triumph, claiming during the campaign: “The only reason Boris is prime minister is because, earlier this year, I had had enough. After the launch of the Brexit Party in Coventry in April ... we managed to get rid of the worst prime minister we have ever seen.”

Farage was a significant figure, able to mobilise the activist minority twice during the decade to put pressure on the Conservative Party from the outside. But it was Johnson, Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings who won the referendum – keeping Farage at arm’s length – and it was the same trio (with less of a role for Gove) who won the election.

The Brexit decade will end, then, on 31 January 2020, a month late. The word will fade down the list of popular internet search terms. The department will be closed down. And Boris Johnson, the Brexit prime minister, invited the new parliament to look to the future: “Just imagine where this country could be in 10 years’ time.” Having triumphed in this decade, he intends to dominate the next.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks