How an exhibition is reviving Anglo-Saxon England: From fearless warriors to timeless jewels

With globalisation establishing English as the planet’s lingua franca, the largest ever exhibition of pre-1066 Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, the first to be written in English, could not be more timely, says Dominic Selwood

Gaze around Britain’s great cathedrals and castles, at the carved stone and painted glass – the biblia idiotarum or “books of the unlettered” – and they eloquently evoke every age back to William the Conqueror. Try to peer back further, though, and everything changes. The visual, intellectual, spiritual, and day-to-day world of the age that came before seems maddeningly hard to grasp.

Back in the 1930s, the authors of 1066 And All That captured something of the frustration: “Egg-Kings were found on the thrones of all these kingdoms, such as Eggberd, Eggbreth, Eggfroth, etc. None of them, however, succeeded in becoming memorable – except in so far as it is difficult to forget such names as Eggborth, Eggbred, Eggbeard, Eggfish, etc. Nor is it even remembered by what kind of Eggdeath they perished.”

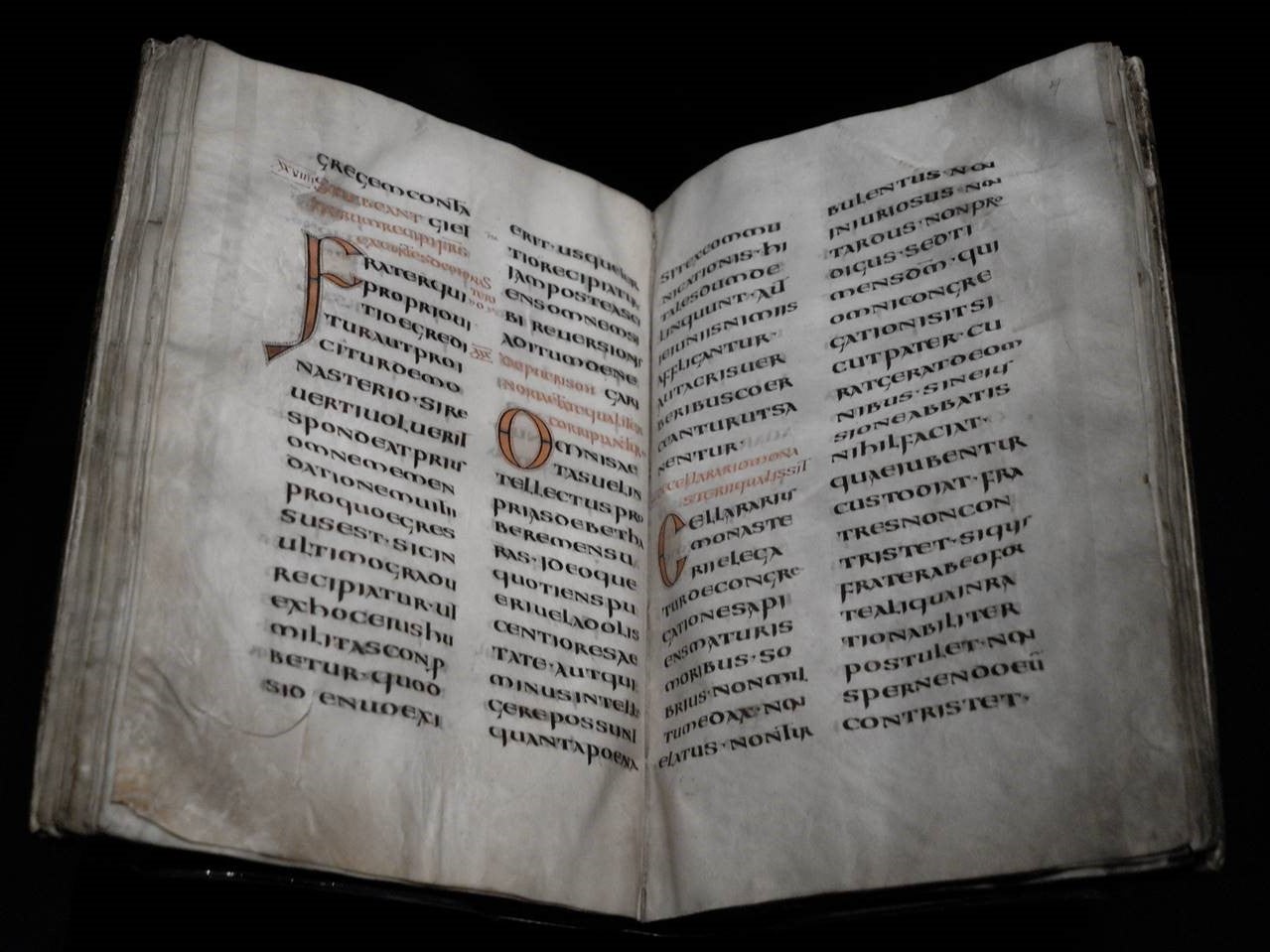

However, the low middle ages are not truly lost. Pre-conquest England is there – it is just well hidden. Occasional church towers or windows and museum cabinets of jewellery hint at a vibrant period, but it is in books and manuscripts that the Anglo-Saxons come vividly alive, delineated in everything from pale rusty ink to lush gold and lapis. In these texts we meet a vigorous and confident cast of warriors and saints, queens and kings, thegns and villagers, dragons and gods.

Anglo-Saxon books are now spread all over Britain and Europe. In a moment of inspiration in 2013, the British Library decided to gather an unprecedented number of them together under one roof.

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is now open, and its 180 exhibits froth and bubble with the whirlpool of fresh ideas and vibrant images that animated England for 700 years. With modern Britain unable to formulate a coherent 21st century identity for itself, the timing of this voyage into the past could not be more relevant.

A quick reminder. Anglo-Saxon England thrived from the early AD400s to 1066. As Roman administrators and military commanders hitched their skirts, clambered onto boats, and waved “Valete!” to Britannia, boatloads of Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians eagerly arrived to fill the vacuum.

The precise details of these migrations remain unclear. Some of the settlers may have been invited as mercenaries to fend off the raiding Scots (from Ireland) and Picts (from Scotland), while others almost certainly arrived to pillage and conquer. Many indigenous Britons were not thrilled. Warlords like Arthur (who may merely be an avatar for others) fought back hard. Yet despite the fierce resistance – the Historia Brittonum tells us Arthur alone slew 960 at the battle of Mount Badon – the settlers prevailed, put down roots, and built communities. Before long the newcomers from modern-day Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands had taken over, and Angle-land (England) emerged.

The British Library’s timing is impeccable because the energetic imagination and international adventurousness of the Anglo-Saxons points to a profoundly dynamic period in which England buzzed at the intellectual, spiritual, artistic, and mercantile heart of Europe.

Although there is little room for the Anglo-Saxons in crammed television schedules and bookshops already groaning with Plantagenets and Tudors, the Anglo-Saxons were every bit as important to the development of England. In fact, more so, as they founded it.

“The Anglo-Saxon period was a formative one, both for the English and their British and European neighbours,” says Dr Levi Roach, a leading expert from the University of Exeter. “Be it in our towns and villages, our shires and counties, even our names for ourselves (‘English’, ‘Welsh’, ‘Scottish’), they have left an indelible mark.”

If you look hard enough, life in modern Britain still has countless legacies of the Anglo-Saxons. Undoubtedly their most important bequest was their language: Ænglisc. (In Old English “sc” is pronounced “sh”, as in biscop or scip.) While the language has always been important in Britain and was exported to the New World and empire, its significance has grown even more in the last generation, with globalisation establishing English as the planet’s emerging lingua franca.

This is very likely the first time in their long history that the codices have been together in the same place; it’s easy to imagine them as in dialogue with one another

English may now be ubiquitous, but we rarely credit the Anglo-Saxons for its deep beauty and profound flexibility. For many – like the prime minister – “Anglo-Saxon language” is merely a periphrasis for swearing. This is a pitiful characterisation. Anglo-Saxon (these days rebranded as Old English) is the bedrock of modern English. And actually, there is no evidence any Anglo-Saxon ever uttered the F-word, the notorious monosyllable, or a wide range of other four-letter words.

When we want to laud the beauties of historic English, instead of celebrating Anglo-Saxon, we usually skip straight to Shakespeare and the King James Bible. But while both have given us shimmering words and phrases, they were doing no more than wrapping ropes of fairy lights around an already solid, beautiful, old and leafy tree. The fact is that long before the Globe Theatre rocked with applause, and even before Chaucer’s pilgrims met at the nearby Tabard two centuries earlier, the Anglo-Saxons were speaking and writing the earliest, luscious English.

“English is a Germanic language,” explains Dr Alison Hudson, co-curator of the British Library’s exhibition. “Anglo-Saxon is the basis of some of its vocabulary and structure.” But the Anglo-Saxons were also devoted linguistic magpies, adept at incorporating new words and ideas. “One of the language’s unique marvels is its flexibility to absorb other elements, like Latin, Old Norse, and Norman French. In this period, we see loan words like ‘pepper’ and ‘cinnamon’ coming into English for the first time. It’s a wonderful reflection of the fact that the British Isles have always been a multicultural place. They even had the word ‘ylp’ for elephant. It’s one of my favourite Old English words. They had no idea what one actually looked like – they imagined it had white polka dots on pink skin – but it was an important enough part of their intellectual world to create a word for it.”

Language weaves its way through the exhibition in a similar way to the bright swirls of decoration burnishing many of the old pages. At the dawn of the Anglo-Saxon era we see jagged runes cut into objects from a time when daily life revolved around the old gods and goddesses. As, in a small way, ours still do. Tiw, ruler of sky and war, is still honoured by a day of the week, as is Woden, head of the gods, Thunor, the thunder god, and Frige, goddess of the home and love. Some of these inscriptions are charmingly timeless, like the discreet marketing on the reverse of a piece of delicate gold, ivory, and garnet jewellery: “Luda repaired the brooch”.

The Anglo-Saxons did not cling to the old Germanic gods for long. In 597 St Augustine arrived to re-Christianise England, and one glass case holds an astonishing 6th century book of the four gospels, in Latin, believed to have been in his luggage.

Augustine and his companions persuaded the Anglo-Saxons to adopt the religion of Rome, and the new converts became some of its most devout followers. Christianity was a book and writing-based religion, and the old runes fell into disuse as Anglo-Saxon scholars adopted the Roman alphabet for Latin and Old English. For a while, though, runes clung on in places. The exhibition has a replica of the 5.5-metre high Ruthwell Cross with its spectacular carvings from the life of Christ, along with several verses incised in runes evoking lines from “The Dream of the Rood”.

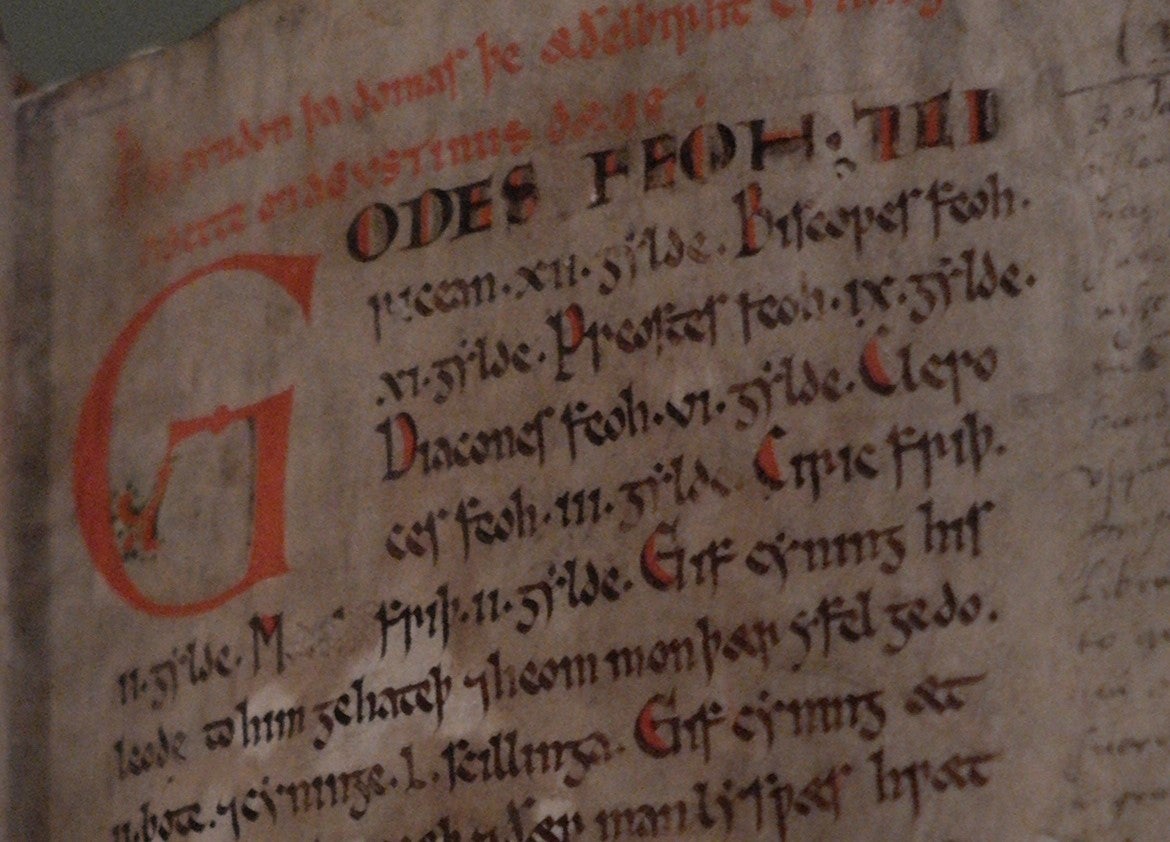

The oldest proper text in Old English is King Æthelberht of Kent’s law code, composed around 600. It is the earliest known utterance of English law, and is the standout exhibit in the exhibition’s first room. It is an extraordinary reminder of just how old our quirky legal system is, with so much of it – including trial by jury – reaching back to principles of Anglo-Saxon justice.

As you would expect, the exhibition features stellar examples of Anglo-Saxon art. The mesmerisingly vibrant decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels (circa 700) needs no introduction, but equally fascinating are the small words glossed in red ink under the main Latin text. They are in Old English, and represent the earliest known version of the gospels in the vernacular. Strange as this sounds, translating the gospels into English was not that uncommon. The Wessex Gospels – also in the exhibition – were widely copied English versions of the four gospels: something later Tudor scholars in the Protestant Reformation pretended to be undertaking for the first time.

What’s amazing about the four great codices is that, for all their riches, they represent just an accidentally surviving tip of an iceberg of poetry long since lost to us

The cases of books in the darkened series of rooms are interspersed with artefacts conjuring up the Anglo-Saxons’ physical world. The Alfred Jewel has pride of place, as do objects like the 5th century pottery Spong Man, which is the earliest Anglo-Saxon sculpture of a person. There are also crowd pleasers from Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire and Binham Hoards.

When Anglo-Saxon England died as a political entity at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, embroiderers depicted the run-up and battle in 58 captioned scenes on 70 metres of linen. Many of its panels show daily life either side of the Channel, preserving one of the richest records of late Anglo-Saxon society. Although the political and military narrative in the Bayeux Tapestry is Norman propaganda – telling their story of why William had God on his side – it is notably sympathetic to King Harold of England, and one of the reasons may be that the embroidery was perhaps made by Anglo-Saxons in Kent. Anglo-Saxon needlecraft – opus anglicanum (English work) – was world famous. The Bayeux Tapestry is not, however, in the exhibition, although President Macron has promised to send it for a visit in the near future, which will be the first time it has crossed the Channel in 900 years.

The Anglo-Saxons were energetic travellers and traders, in constant contact with Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. In one glass case there is an astonishing late 4th century book that made it to Anglo-Saxon England all the way from North Africa – possibly in the baggage of Hadrian, a “vir natione Afir” (man of African birth) who travelled to England in 669 and ended up as abbot of Canterbury. In another is a gold coin minted by Offa, who ruled Mercia from 757-96. Although it predictably reads “Offa Rex” on the front, it is modelled on an Islamic dinar, with Arabic writing on the back including “there is no God but Allah alone”. With travel came a thirst for knowledge, and the Anglo-Saxons were also scientists. Books in the exhibition contain diagrams of the planetary orbits and affirmations that the Earth is round.

For the real soul of the Anglo-Saxons – the rhythms of their lives, loves, and deeds – there is one standout case. In it are just four books whose names will have any manuscript nerd’s pulse racing. The first is the British Library’s own Cotton Vitellius A XV. It is fire ravaged, but magically preserves the sole surviving copy of Beowulf. Alongside it lies the Vercelli Book – in Britain for the first time in 900 years – containing the only manuscript version of the mystical and haunting “Dream of the Rood”. Next to it is the Junius Manuscript from the Bodleian. Its poems have largely religious themes, and the page is open on “Genesis A”, which offers a good sense of their preoccupations with its nine mentions of heofan and helle. The final volume is the Exeter Book, on loan from Exeter Cathedral. It shimmers with dozens of well-known, ravishing poems, including “The Seafarer” and “The Wanderer”, and lies open on a riddle asking which creature eats words but gains no wisdom. (Spoiler: a bookmoth.) Apart from the transcendent beauty of the words and imagery in these four books, an equally extraordinary feature of them is that they contain around 75 per cent of all surviving Old English poetry.

“What’s amazing about the four great codices is that, for all their riches, they represent just an accidentally surviving tip of an iceberg of poetry long since lost to us,” explains Professor Carolyne Larrington, an expert in Old English and medieval European literature at Oxford. “This is very likely the first time in their long history that the codices have been together in the same place; it’s easy to imagine them as in dialogue with one another.”

The single manuscript copies of Beowulf and “The Dream of the Rood” witness the remarkably poor survival rate of Old English texts. This has nothing to do with either the amount the Anglo-Saxons wrote or the quality of their materials. They wrote prolifically, and their vellum and bindings were perfectly robust, as many books in the exhibition demonstrate, with thumping leather-tooled and richly gem-studded covers showing no signs of fragility.

The loss of so much Anglo-Saxon writing has far more to do with the purposeful and systematic 16th century destruction of monastic and university libraries by the Tudors, whose religious policies saw bonfires and rubbish heaps made of books that referred to England’s medieval faith. Religious sculpture, too, was also decimated. The original Ruthwell Cross, with its extraordinary runic poetry inscriptions, was smashed into fragments by Protestant extremists in the 1640s, but was meticulously reassembled in the 1820s, and now stands inside Ruthwell Church in Dumfriesshire.

Later, a handful of notable figures tried to repair the damage and locate the books and manuscripts that had been scattered. “Despair over the fate of the contents of monastic libraries crossed confessional boundaries,” explains Professor Helen Parish, an expert in late medieval and Reformation history at the University of Reading. “The former Carmelite turned ardent evangelical, John Bale, had little sympathy with the trappings of monasticism, but still complained bitterly that the dispersal of the libraries was to the shame of the country. Matthew Parker, first archbishop of Canterbury in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, worked hard in the 1560s to recover lost books and records. His library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, provided the building blocks for a new history of the English church, and a burgeoning sense of national faith and identity in which the Anglo-Saxon church was the cornerstone.”

One especially notable feature of the surviving corpus of Old English poetry is the prominence of women characters. Hudson explains: “There are a surprising number of Anglo-Saxon epics of strong women. Biblical characters like Judith, saints like Juliana – a Middle Eastern martyr who battled and conquered demons – and royalty like the Empress Helena. In the Genesis poem in the Junius manuscript, even Eve emerges as a notably prominent character.”

Strong women are not only part of the Anglo-Saxons’ poetic world. They were part of everyday life, too. Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred and wife of Æthelred of Mercia, was named “Lady of the Mercians” and did more to bring England together as a country than possibly anyone else. Her deeds are recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which sits in the same room as the four poetry books. Less regal Anglo-Saxon women’s lives are also fascinating. The exhibition has the late 10th or early 11th century will of the noble widow Wynflæd, and it contains two arresting provisions. On her death she freed some of her slaves, but not Eadgifu the weaver or Æthelgifu the seamstress. And she could read, as she carefully passed on her prized collection of books.

If asked to name an Old English poem, many people would nominate Beowulf. It is rightly one of the most famous stories in Anglo-Scandinavian literature, and the original manuscript does not disappoint. The poem’s 3,182 lines throb with a ripping tale of the warrior Beowulf’s mortal combat with the monster Grendel and his mother and, years later, with a dragon. The epic’s ability to transfix and delight wins new admirers every generation: most recently with Nobel prize winner Seamus Heaney’s free translation in 1999 and Hollywood warhorse Robert Zemeckis’s epic A-list motion capture blockbuster in 2007.

After Beowulf, the most famous Old English poem is “The Dream of the Rood”, in which the cross of the crucifixion tells its version of the passion story. It opens with the writer having a vision of the cross that will soon speak to him:

Hwæt, ic swefna cyst secgan wylle,

hwæt me gemætte to midre nihte,

syðþan reordberend reste wunedon.

þuhte me þæt ic gesawe syllicre treow

on lyft lædan leohte bewunden,

beama beorhtost.

Listen! I wish to tell of the best of dreams,

which I dreamt in the middle of the night

after the speech-makers were in bed.

It seemed to me that I saw a most wondrous tree

rise into the air, enveloped by light,

the brightest of trees.

(You only need to know two things to read it aloud: “æ” is pronounced “a” as in “cat” and “ð” and “þ” are both pronounced “th”.)

If you read, it, two things pop out immediately. The first is that the sound and cadences are deeply rhythmical, and almost certainly mean it was recited to music. The second is that the phrases are built up with a hypnotic alliteration that is perhaps the most defining characteristic of Old English poetry.

It is, obviously, more challenging than Shakespeare or Chaucer as it has many unfamiliar words and comes complete with case endings. We have managed to get rid of most of them in modern English, although a few like “them” and “whom” stubbornly remain. To add to the challenge, many Old English words have also changed their meaning over time. For instance, “spell” simply meant “story” to the Anglo-Saxons.

Old English also had dialects which evolved. The main ones were based in Northumbria, Mercia, Kent, and Wessex, with Wessex eventually coming to dominate, as it was the language of King Alfred – who was a fervent promoter of literacy – and later of Ælfric, abbot of Eynsham, who wrote and standardised the language prolifically.

Despite the strange look and feel of some Old English words, there is no reason to be put off. It is not as alien as it may sometimes seem. Neither does it only live in universities, libraries, and museums. JRR Tolkien was an Oxford professor of Anglo-Saxon for years, and if you enjoy any of the vocabulary of Middle Earth, you are revelling in his profound skill at playing with ancient Germanic-style languages.

Other standout treasures in the exhibition include the pocket-sized St Cuthbert Gospel, which belonged to St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (died 687). It is the oldest European book with an original intact binding, in this instance an exquisitely decorated red goatskin cover, all miraculously preserved by having been placed into the saint’s tomb alongside him.

Another is the bible known as the Codex Amiatinus. It was produced alongside the St Cuthbert Gospel at Wearmouth-Jarrow but, by contrast, is vast. With a spine over a foot thick, it takes two people to lift it and is the largest book in the exhibition. It was once one of three identical copies, but Amiatinus is the only one to survive, as soon after it was finished Abbot Ceolfrith (died 716) took it to Italy as a gift to the pope, and its homecoming to England for the exhibition is the first time it has been back in over 1,000 years.

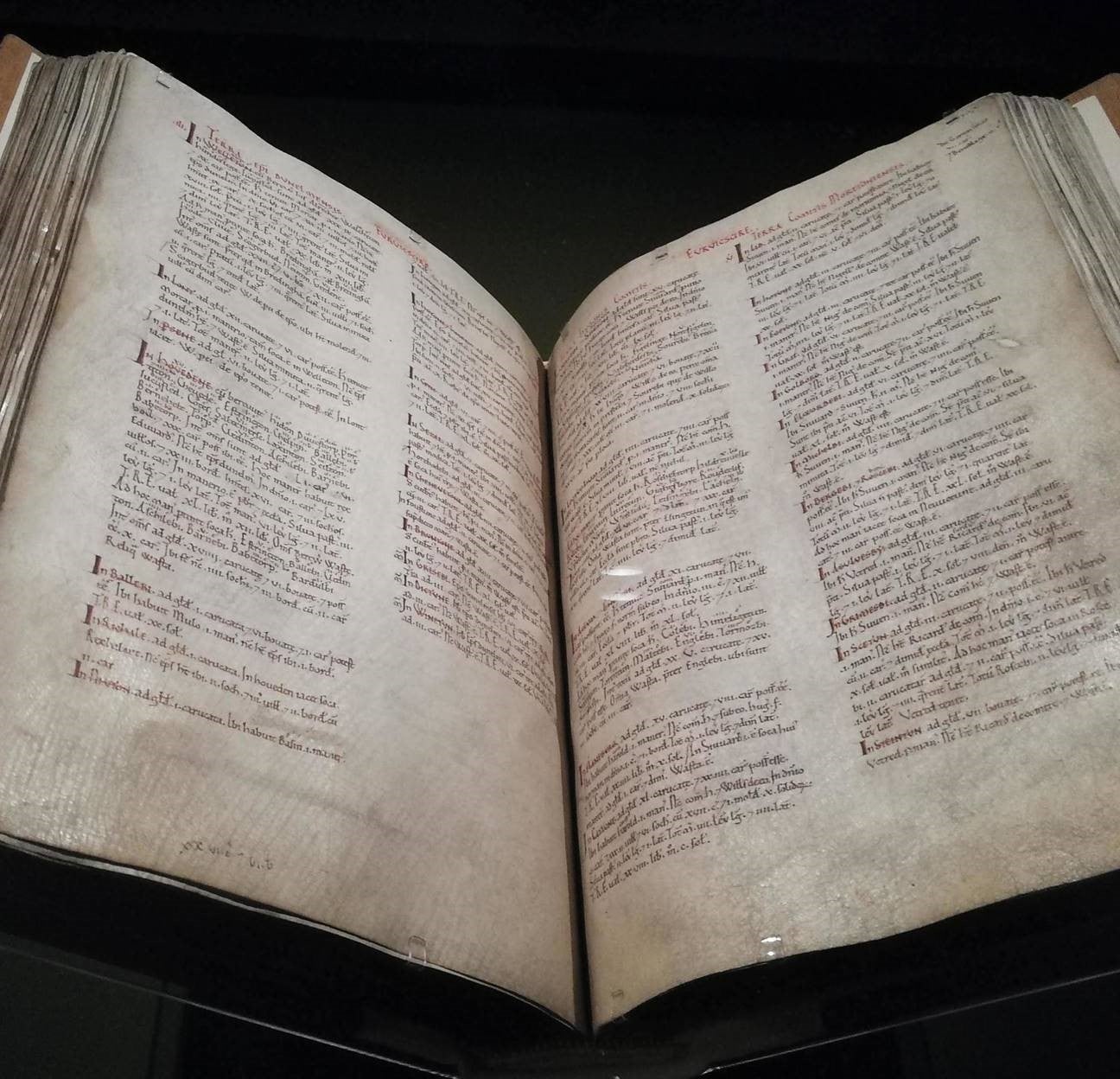

In the final room of the exhibition, beautifully lit and residing in a central case, is the most famous book ever produced in England. At Christmas 1085, William the Conqueror ordered a survey of his country, its land, and how it was occupied. Foremost in his mind was – as so often with rulers in any age – the question of property ownership and how much tax he could raise from it. Thanks to the Anglo-Saxons’ meticulous organisation of England into counties and hundreds, the research only took his commissioners until 1 August the following year. When it was all written up, the result was nicknamed the Domesday Book, from the Old English “domesdei” – meaning the Day of Judgment – because the book’s record, like that of the Last Judgment, was unappealable.

On one level, the legacy of the Anglo-Saxons is something that is better appreciated outside England. We call the world’s English-speaking countries the “Anglosphere”, whereas the French choose the more nuanced “le monde Anglo-Saxon”, hinting at a distinct historic, linguistic, cultural, and philosophical heritage.

The French also have no real concept of “the Dark Ages”, and the equivalent period in France has no label implying that it was unenlightened. Of course, as the exhibition demonstrates unequivocally, there never was a dark age. It is a myth dreamed up by Whig historians wanting to believe that Europe collapsed from glory into barbarity with the fall of Rome, but from the Normans onwards the British Isles marched unstoppably towards ever more profound progress and civilisation. The other reason the French have no dark ages is, of course, that they did not experience a regime as violent with history and cultural property as the Tudors.

It is shameful that we so often start our islands’ history and lists of kings and queens with William the Conqueror, as if before his arrival there was a void with darkness over the deep. Britain had spectacular cultures before 1066, of which the Anglo-Saxons were one. Theirs was an intense, vibrant, literate, artistic, creative, spiritual, intellectual, practical, adventurous, outward-looking, European world. It was also a prize well worth conquering, which is why Cnut the Dane seized the throne in 1016 and William of Normandy followed him 50 years later. Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War has managed the Herculean task of comprehensively demonstrating why.

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War, at the British Library from 19 October 2018 to 19 February 2019

Dr Dominic Selwood is a historian and barrister. He is the author of ‘Spies, Sadists and Sorcerers: The History You Weren’t Taught at School’, and the crypto-thrillers ‘The Sword of Moses’ and ‘The Apocalypse Fire’. He tweets as @DominicSelwood

The author expresses his deep thanks to Dr Levi Roach (author of ‘Æthelred The Unready’), Dr Alison Hudson (author of the British Library’s Medieval Manuscript Blog), Professor Carolyne Larrington (author of ‘Winter is Coming: the Medieval World of Game of Thrones’) and Professor Helen Parish (author of ‘Monks, Miracles and Magic: Reformation Representations of the Medieval Church’) for being interviewed for this piece

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks