My Romanian father was broken as much by Brexit as by leukaemia

Romania is the only country that overthrew communism with violence, executing its leader and his wife on Christmas Day 1989. Marina Cantacuzino’s life is intimately and painfully bound up with that event. Here she tells her story

On the night that Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu were shot by firing squad in full sight of TV cameras, their bloodied corpses seen around the world as they lay sprawled on the ground behind a courthouse in the town of Targoviste, my grandmother, a Romanian exile living in a cottage in a small village in Kent, lit a candle in her window and prayed for her country’s deliverance. She would never have cheered such an execution, but there was no question in her mind that the dictator whose brutal rule had condemned millions of her countrymen to death and suffering deserved what he got.

My family’s story was intimately bound up in Romania’s tumultuous 20th-century fortunes, and it’s why even now, 30 years on, the fall of Ceausescu raises so many questions in my heart and in my mind.

I have never lived in Romania, but those questions remain – of identity, of perceptions – and somehow they grow more urgent with the passage of time. What is this country where my family’s roots run so deep? And what is it about the associations that Romania triggers in the outside world? I wish my grandmother was still around to help me answer these questions, but she died in London in 1992.

As a child in the 1960s – born in the UK but half-Romanian, with the name to prove it – I was considered exotic. Romania had that effect on people. With its Romance language, Eastern Christianity, historical invasions from the Romans to the Ottoman Empire – not to mention the enduring legacy of Dracula – Romania had always sounded like a far-away fantasy land. The long years of communism only added to the mystery, with Ceaușescu’s grotesque concoction of tyranny and lies holding a grim fascination for the west. While 23 million Romanians lived in poverty, Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu lived a life of staggering opulence.

I went to Romania once during those years. In 1976 my sister Ilinca and I, both teenagers, accompanied our father to the country of his childhood on a Swan Hellenic lecture tour which he was leading. Here we saw the Unesco world heritage sites of Moldavia’s painted monasteries and the wooden churches and Saxon villages of Transylvania. We also discovered a peasant way of life still very much alive in the villages, with mud tracks so impassable in wet weather that only horses and carts could be used for transport. Yet despite the historical landmarks and staggeringly beautiful countryside you could never forget you were behind the Iron Curtain. Steeped in the bleak unworkable economics of communism, with its polluting industrial wastelands and severe food shortages, Romanians looked miserable, drab and cold.

Relatives of mine who grew up under communism were given permission to know who among their friends, relatives and former employees had spied on them. They chose not to know

Most of my relatives had by now left but a few remained. My sister, father and I spent long hours in dimly lit apartments heavy with Soviet-style furniture, eating papanasi custard donuts and sipping Palinka. We were a happy distraction for those left behind, but outside on the street it was much less welcoming. Policemen stood on every corner and strangers viewed us with suspicion. We were warned that the Romanian secret police (the Securitate) were ubiquitous. In fact, it is now believed that one out of four Romanians was an informer. Recently, relatives of mine who grew up under communism were given permission to know who among their friends, relatives and former employees had spied on them. They chose not to know.

I visited Romania again a few weeks after Ceausescu’s execution with a plane-load of other journalists who were finally being given access to the only communist state in Europe to have used violence to overthrow its government. We walked down the snow-filled avenues of Bucharest, the morbid stillness and deserted streets not just a memory of Ceausescu’s authority but a reminder that this was a country on its knees. And yet despite the economic chaos of communism having left its citizens with neither fuel for their cars nor food for their larders, ordinary Romanians were convinced they would soon be released from the misery of their daily lives.

Somewhere along the way since 1989, the distance between Romania and the UK narrowed. Romania joined the EU in 2007 and with the free movement of people fully in place by 2014 young Romanians came in large numbers to pick our fruit, build our houses, clean our homes and work in the NHS. Suddenly, close up and personal, Romanians were now viewed in a somewhat less favourable light – hence my neighbour’s comment when I was heading off to Romania, again with my sister, earlier this year: “Watch your purse”. The comment hurt, but the prejudice was widespread.

Long after the death of the Ceausescus, which had promised a better Romania, the country became the embodiment of chaos and corruption, an image not helped by the small number of ethnic Roma beggars who arrived in the parks and playgrounds of Europe from the ex-socialist countries of Romania, Bulgaria and Albania.

The sorrow I felt at this turn of events derived from the fact that I have always described myself as half-Romanian even though I was born in England and don’t speak the language. But I can always recognise Romanian when it’s spoken, having grown up hearing my grandmother talking to my father – or, as was often the case – shouting noisily down the phone to relatives. I have held on to my Romanian surname despite being married, and for more than feminist reasons. I love Romania’s history and the questions that arise because of it; the nods of recognition my name receives when I pass through customs in Bucharest or when visiting my parents (now deceased) in hospital when Romanian nurses working for the NHS would recognise the name and hope to get a chance to speak their native tongue.

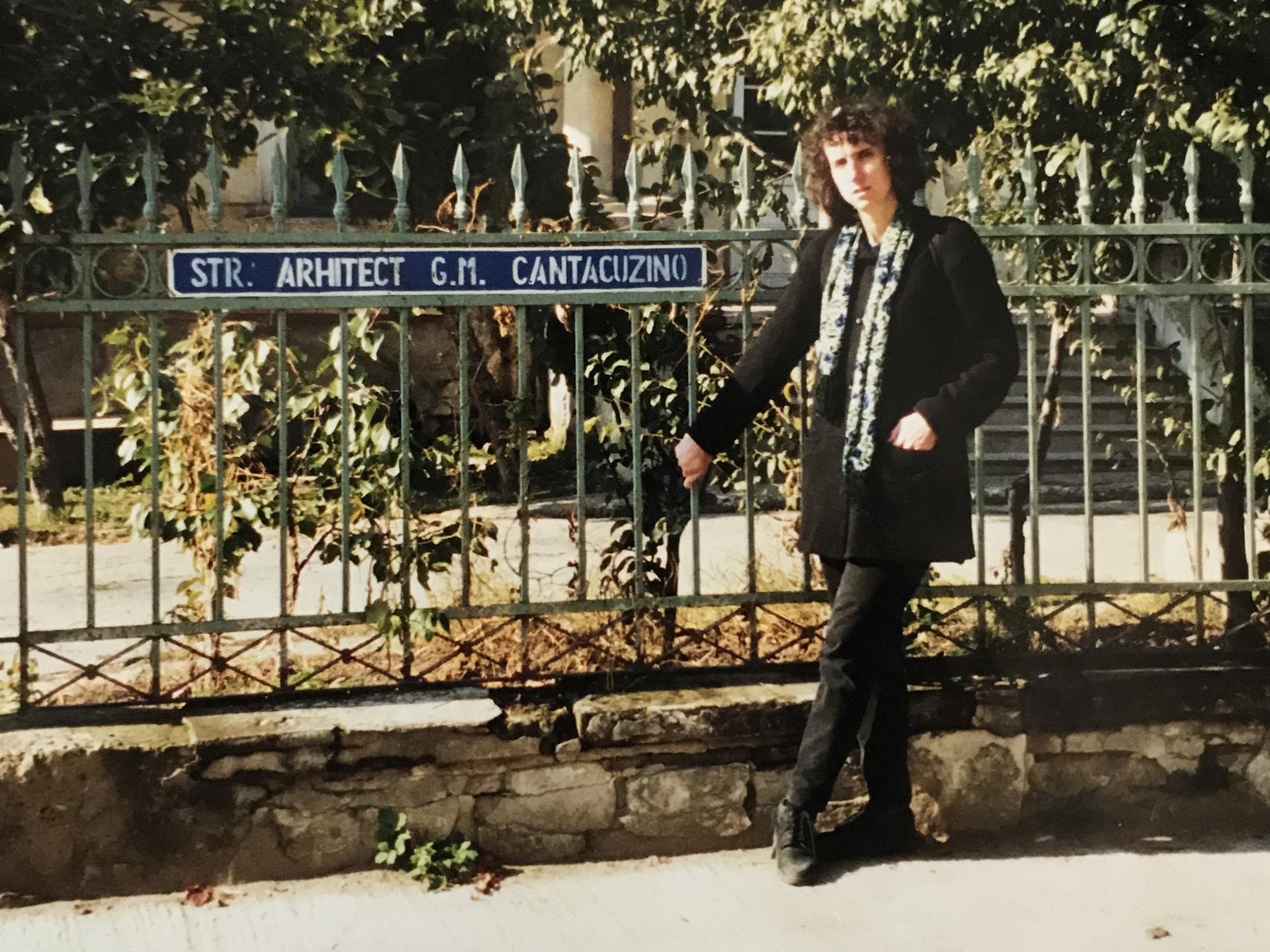

My father, Sherban Cantacuzino, went from Bucharest to a Hertfordshire prep school in 1939 when he was 11. My grandmother hadn’t planned to stay but soon after they arrived Britain was at war with Germany. The following year, my grandmother made a mad dash back to Romania to collect her younger child, Marie-lyse, who had been staying with her grandparents. That Christmas, my grandfather George Matei Cantacuzino, a Romanian aristocrat and well-respected architect and writer, visited his family in England before returning to Bucharest. The war was not expected to last long and the family were convinced it was a storm to be weathered before they would all be reunited.

It is said that Romania’s war was unheroic. Initially, the country adopted a position of neutrality before in 1941 it began fighting alongside the Germans and then switched sides after a coup in August 1944 to support Stalin’s Soviet Union. After the occupation by Soviet troops in 1947 my grandfather, who had been a war artist in the Crimea and Stalingrad, was classified by the communists as a “person of unclean origin” and refused permission to join his family in England who he never saw again. Later he was arrested and sentenced to five years hard labour at Aiud Prison Camp in Transylvania. He died in Iasi in 1960, aged 61.

My grandmother was stoical about her loss but her sunken blue eyes could not hide her sorrow. During the war she was classified as an enemy alien and wrote recipes under a pseudonym for an illustrated women’s magazine called Britannia and Eve. For someone who had never had to cook in her life, she had an amazing capacity to adapt.

Sanda Cantacuzino was a Romanian princess with a halo of silver hair and a predisposition for premonitions. She was an intriguing mix of aristocratic restraint and earthy naturalism and would often tell us that she was far happier living the modest life of a chicken farmer in Kent than she had ever been as a young woman of wealth in Romania. In the Kentish village where she lived for over half her life she was simply known as The Princess – not a title spoken in reverence, just a fact.

I am convinced that when he died, in February 2018, my father was broken as much by Brexit as by leukaemia

As children we spent every Christmas, Easter and long summer holiday in my grandmother’s tiny cottage, with its heavy middle-European atmosphere. Often our cousins joined us; at Easter we painted eggs, and on New Year’s Eve we put burning hot metal into a bucket of cold water to watch it sizzle while it formed weird, gnarled shapes which my grandmother would then study intently before predicting the next 12 months of our young lives. Each night she’d sit at the end of our bed telling us stories of the country she’d left: how the family dated back to the Byzantine Kantakouzenos emperor of 14th century Constantinople and how in the 17th century the family were granted approval by the Holy Roman Emperor to use the royal title of Prince and Princess. She told us of her home at Darmanesti, with its wide vistas overlooking the Carpathian mountains, where bears roamed the woods and servants raked the gravel driveways dawn and dusk.

After the end of communism in 1989 my father returned frequently to Romania, leading private tours for family and friends and founding the charity Pro Patrimonio (a version of the National Trust of Romania). As Romanians began to come to the UK in increasingly large numbers, he too noticed their deteriorating reputation, particularly in the lead-up to the 2016 EU referendum when the debate about foreigners turned nasty. I am convinced that when he died, in February 2018, he was broken as much by Brexit as by leukaemia. He couldn’t understand how the country that had welcomed him in 1939 could now so enthusiastically turn its back on Europe. It felt intensely personal to him.

One of the last books he ever read was Keith Lowe’s Savage Continent. It is an account of Europe between 1945 and 1948, a continent consumed by vengeance, where after countless massacres “in the name of nationality, race, religion, class or personal prejudice”, virtually every person “had suffered some kind of loss or injustice”. My father still remembered with horror the terrible explosion of violence that followed the end of the Second World War, and he believed that leaving the European Union put peace and security at grave risk.

When earlier this year I returned to Romania with my sister and our husbands, Brexit was a popular topic of conversation. Romanians seemed as bemused as the rest of Europe as to how the moderate and courteous British could have become so belligerent. As we travelled north from Cluj towards the Ukrainian border I noticed that while the rural idyll of haystacks, traditional timber houses and horses pulling carts along dirt roads had endured, Romania had become a more stable and sophisticated country since I was last there, packed with universities and entrepreneurs and with an economy 30 per cent larger (in real terms) than it had been 10 years before.

I was told that young Romanians who had left their villages to work in Europe were starting to return; some renovating traditional wooden huts, others building modern houses that often remained unfinished. Since Romania joined the EU, an estimated 3.6m people, 16 per cent of the population, have left the country. Just as Ceausescu in the past had put up an iron fence to keep his people in, now some politicians would like to do the same to address labour shortages and the brain drain. The Romanian exodus to other EU countries has become a hot political issue for one of the EU’s poorest member states.

Perhaps to make up for all those years of communist isolation, Romanians, it seems, still crave the company of strangers and are more eager than ever to indulge foreigners with their hospitality and generosity. Whatever the state of their homes, Romanians always invite you in and love to share elaborate meals with guests. In his book Along the Enchanted Way (2009) the author William Blacker, who spent eight years living a traditional life among the gypsies in northern Romania, concludes that Romanians “were the kindest, gentlest and most civilised people I had ever met”.

Despite the fact that so many of the British now hold an image of Romanians as gypsies and thieves, if you ask any tourist who has recently visited the country, they are likely to agree with Blacker. In fact the Institute for Economics and Peace has rated Romania the 24th safest country in the world coming several places above the UK. And I can vouch for that. On my return from Romania I admit that I took some pleasure at being able to tell my neighbour that my purse wasn’t stolen the whole two weeks I was there.

Marina Cantacuzino is a writer, campaigner and the founder of The Forgiveness Project

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks