Where is the honour in honour killing? Mark Billingham’s new novel is both brilliant and unbearable

In his latest crime story, ‘Love Like Blood’, novelist Billingham explores the horror of killing in the name of pride – based on a true story it unsettles as it unravels a culture of brutal misogyny

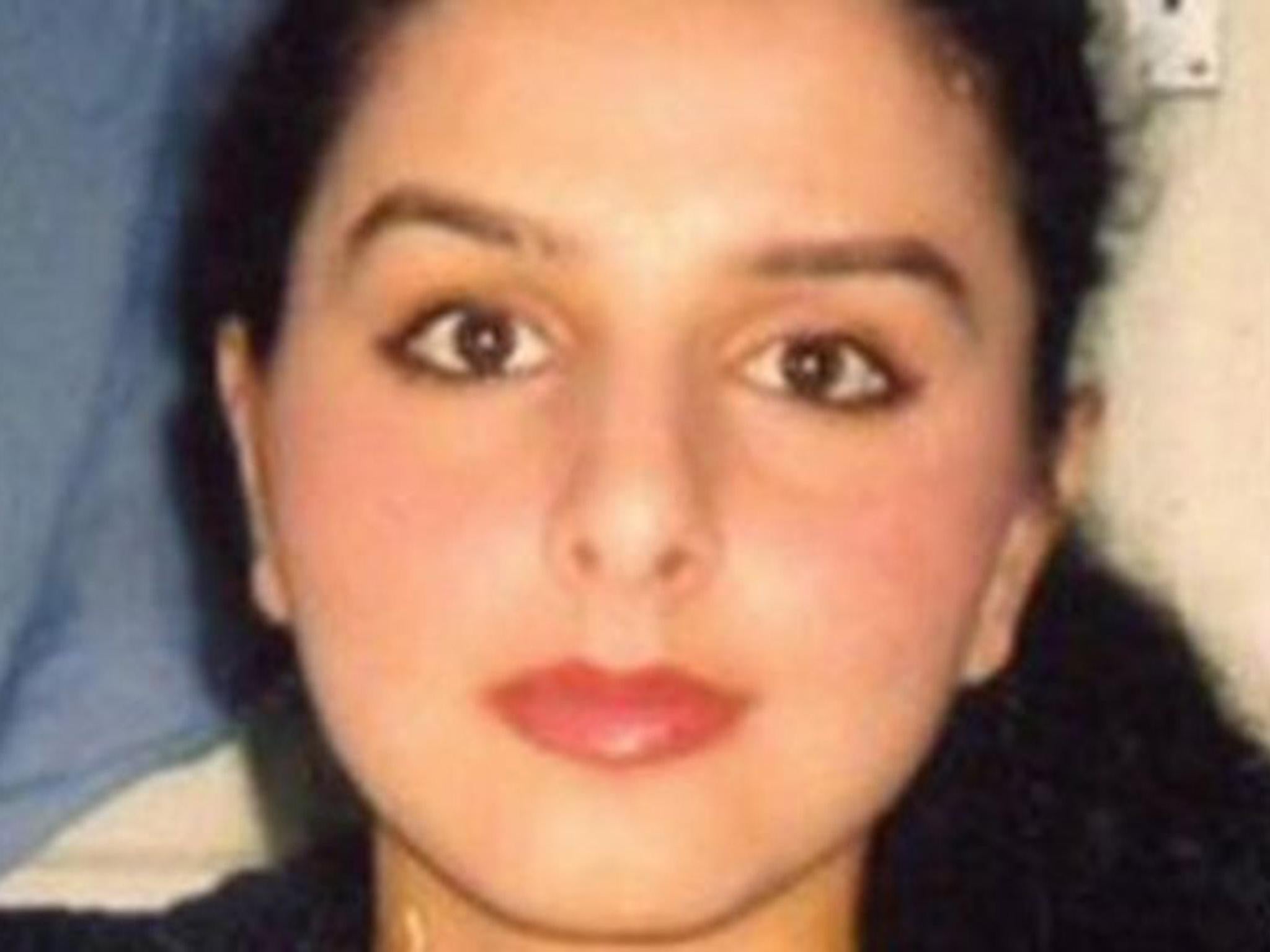

Banaz Mahmod knew she was going to die. And no one was going to lift a finger to help her. She went to the police anyway, in Mitcham, south-west London, where she lived. This was back in 2005.

She was an Iraqi Kurd who came to London when she was 10. She was an attractive young woman and forced into an arranged marriage with a man who proceeded to abuse her physically and sexually. He owned her. She was just an object, a toy, a victim. This was his right – to his way of thinking. So she left him and then fell in love with another guy. Which was not allowed according to the honour code as understood and interpreted by her uncle, Ari Mahmod, and her father, Mahmod Babakir Mahmod.

The arranged marriage and all the physical and sexual abuse, that was all just fine. But not this falling in love nonsense, with someone not officially selected, not when she had already been satisfactorily married off. The father and the uncle thought she deserved to die for offending against the code and thus bringing shame on the menfolk. And so they set about trying to kill her.

Which is when she went to the police. (You can actually watch a heartbreaking video of her pleading for help, in vain, on YouTube, specifically complaining that her husband rapes her.) She went a total of five times. The last time was after her father had tried to kill her. She escaped and went to the police with injuries, on New Year’s Eve, 2005. The police put it down to one more drunk young woman getting into trouble. Nothing out of the ordinary. PC Plod even threatened her with a charge of wasting police time. Nobody bothered to connect up the dots. Not until it was too late.

So in January 2006 the father and uncle enlisted the help of some cousins. Three to be exact. They effectively outsourced the murder. The cousins did the job properly. The uncle set her up, luring her to some lonely location. Then the cousins kidnapped Banaz, raped her, tortured her, and strangled her with a bootlace. Her body was dumped in a suitcase, then buried in a back garden in Birmingham. She was just 20 years old.

“It was the most disturbing case I had ever come across,” said Mark Billingham, the bestselling thriller writer and creator of rule-breaking Tom Thorne, one of the nation’s favourite detectives. “To be fair, after she died, the police did a good job of tracking them down. Caroline Goode... that was the name of the chief investigator. She wouldn’t let it go.”

Despite the general attitude of omerta from the Kurdish community, detective chief inspector Goode eventually put a total of seven people away for the crime. Murder. “Unlike most cases, she wasn’t doing it for the family. In this case it was the family who were responsible for murdering their own.”

Billingham read about the case, and saw a documentary on the subject – a seed was planted, a seed that led to him to write a novel, 10 years down the road on the subject of honour killings. When he was halfway through writing Love Like Blood, in May last year, Rahmat Sulemani hanged himself.

Sulemani was the man Banaz had fallen in love with. They had planned to break away from her husband and her family and start a new life together. Then she was murdered. He never got over it. Seeing her killers brought to justice did not erase his suffering. He thought time would ease the pain. It didn’t. So he killed himself.

“She was my present, my future, my hope,” he wrote, shortly after her death. “She was the best thing that ever happened to me. My life went away when Banaz died. There is no life.” It was virtually a suicide note. Apparently the older sister of Banaz, Bekhal, is still in hiding, in fear of her life, having given evidence for the prosecution.

Billingham kept on writing as a way of bearing witness. Detective Tom Thorne is recruited to solve a hideous crime. There are honour killings, dodgy relatives, ruthless hitmen, red herrings, plots and counter-plots. Having read an advance copy, I can say that it is (a) brilliant; (b) almost unbearable. The reader will be as furious and filled with pity and terror as Billingham was. Love Like Blood is, as they say in the movies, “based on a true story”. But it’s not just the story of Banaz and Rahmat (which gets a brief shout-out in the book).

There are approximately a dozen so-called “honour killings” annually in the UK. In her book Heretic, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born, self-described apostate who herself ran away from an arranged marriage, reports that 5,000, year-on-year, around the world, “is the most commonly cited estimate”, with almost a thousand honour killings committed in Pakistan alone. But according to police figures, given that these crimes are massively unreported, if we include assault, mutilation, kidnap, and acid attacks under the heading of “honour-based violence”, the true figure for the UK alone would be closer to 20,000.

Globally, that is telephone numbers. Something astronomical. Any woman who deviates from some arbitrary patriarchal law is potentially at risk. You can be killed for “immodesty”, for singing, looking out of the window, or just speaking to the wrong guy. And the problem is getting worse. Between 2010 and 2013, the number of calls received by Karma Nirvana, a UK helpline for victims of forced marriages and honour crimes, rose by 47 per cent.

“There is often little or no incentive to bring [these crimes] to the authorities in countries where the authorities sanction them,” says Hirsi Ali. She cites the case of a woman in Pakistan who married against her father’s wishes and was duly stoned to death in broad daylight outside the courthouse in Lahore. Another girl, still at school, was shot dead while doing her homework because her brother suspected her of being with a man. Case dismissed.

Statistics vary, but according to a poll conducted by the BBC in 2013, 69 per cent of British Asians across all faiths believe that families should live according to the code of honour or “izzat” (or “sharif” for Hirsi Ali).

Every religion is an alibi for regulating and controlling the sexuality of women. But as regards, specifically, the phenomenon of honour killing, the three religions which are most culpable are Islam, Hinduism and Sikhism. Honour, said Shakespeare’s Falstaff, is “air”. Now it means something like the defence of male entitlement, at all costs. Billingham tries to distinguish between the religion, which he respects, and the crime, which he abhors. He argues that honour killing is “a cultural thing not a religious thing – it comes out of South Asia.” He has a believer, in the novel, making the case that the true religion is really all about peace: “Do not harm yourselves or others”, quoth the Prophet.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, on the other hand, puts the blame squarely at the door of the religions in question and especially draws attention to the violence against women that she sees inherent and explicit in the Koran. “It specifically mandates unequal and cruel treatment of women,” she wrote in Nomad. “For instance, chapter four, verse 34 instructs men to beat the women from whom they fear possible disobedience.”

Admonish and scourge. There is a debate here about causation. Maybe it’s just easier (but, in some ways, not easy at all) for an ex-Muslim to make a case against religion than a white guy born Church of England. But what both writers agree on is the fundamentally criminal aspect of “honour”. It conflicts with the basic human right not to have the life squeezed out of you. Billingham’s book, perhaps without intending to, makes Hirsi Ali’s argument for a “reformation” of her own rejected religion all the more cogent.

“I’ve always thought, if you write a book with an agenda you’re going to write a bad book,” says Billingham when I speak to him. “And I’ll stand by that. Even if I’m writing something topical, the story has got to be front and centre. And it has to be character-driven. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not above having a serial killer in my books. I’ve done them before and I will do them again. I love a good serial killer. But every now and then I write something that I feel draws attention to a social issue that isn’t getting discussed enough. It still has to work as commercial fiction. Otherwise I’m not doing my job. Like stand-up without laughs. But it’s something I feel has to be written.”

He wrote Lifeless about homeless guys getting bumped off when he discovered that four out of five of rough sleepers are ex-servicemen. And In The Dark zeroes in on black kids from inner cities being pressured into joining gangs. Love Like Blood belongs in the same category of what I am tempted to call an angry-young-man novel, even if Billingham is, technically, a fit-looking 50-something, married with a couple of kids, and living in north London. I’d say “angry-middle-aged-guy” but I guess that’s never going to catch on.

He began as an actor but switched to doing stand-up in 1987. Then he started writing crime fiction in 2001 with Sleepyhead. For the next few years he was, as he puts it, “crafting dark gritty fiction by day and cracking cheap jokes by night.” Having won the Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the year award twice, he now tends to save the jokes and the rapier-like put-downs for literary festivals in Edinburgh and Cheltenham.

Tom Thorne is not Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s pulp hero, with a gun in one hand and a wisecrack on his lips. But he is capable of a certain sardonic, black humour all the same, as per his creator. In Love Like Blood, DI Nicola Tanner, his female (lesbian) counterpart, gets one of the most telling lines: “Honour killings have also been documented in Jewish and Christian communities. Actually, I think the only ones without any blood on their hands are Buddhists and Rastafarians… Maybe Jedis.”

Only science fiction writer Philip K Dick, with his “pre-cogs”, offered to stop crime before it actually happens (see Minority Report). But other noir novelists are at least offering sympathy for the victims. Maybe this explains why the crime genre is so huge. Everybody is a potential criminal, but statistically you are far more likely to be one of the victims of crime. You may be paranoid but they really are after you.

Billingham says that there was a natural continuum between his career in comedy and his writing: “Neither is a proper job”. But his remark reminded me of the theory of early 20th-century French philosopher Henri Bergson in Laughter, his classic essay on “the meaning of the comic”, that we laugh to have our revenge on those who transgress or offend against reason, in particular when they exemplify “mechanistic inelasticity” or “rigidity”.

Tragedy is strangely akin to comedy. Love Like Blood is an exercise in revenge against the inelastic, murderous, self-deluding code of honour.

Mark Billingham’s new novel, ‘Love Like Blood’, is published by Little, Brown at £18.99. Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing’ and teaches at the University of Cambridge

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks