How to spot a Nazi? Telltale signs include a taste for torture and a dogmatic definition of beauty

The world is haunted right now by the spectre of Nazism. Andy Martin thought the zeitgeist in America was reminiscent of Paris in 1968. He stands corrected: legendary critic Harold Bloom tells him it’s more like Berlin in 1934

“You look like a bit of a Nazi.” With small variations, I’ve had that a few times. I would say more Nordic. More Viking, if you insist. But when I was growing up, the father of my best friend – Irish, who had come through the Second World War (the father, that is) – was convinced that I must have a strong German connection. Of the genetic kind. The offspring of some wandering Luftwaffe officer who ditched in the East End, perhaps. “You bombed the shite out of Romford!” he used to say, with a chuckle, and a certain respect. Denial, clearly, was futile.

Which might go some way towards explaining why I was a fan of Philip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle and Len Deighton’s SS-GB long before they were made into highly watchable television. What if the Nazis had won? My old Irish friend was convinced that I would have slotted right in. Looking good in the long leather coat and the boots. Gleaming and buttoned-up. Officer material. So I would like to point out that my own personal fantasy, where the Second World War was concerned, was that I would have been so fluent in French that I could have been parachuted into Occupied France, behind enemy lines, and passed myself off as a native, blowing up railway lines, joining the Maquis, and shooting the shit out of Fritz. All of these counterfactual Nazi-slanted dramas are essentially transpositions of what it was really like in France if you didn’t happen, like Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, to catch the last train out of Paris as the Nazis marched in.

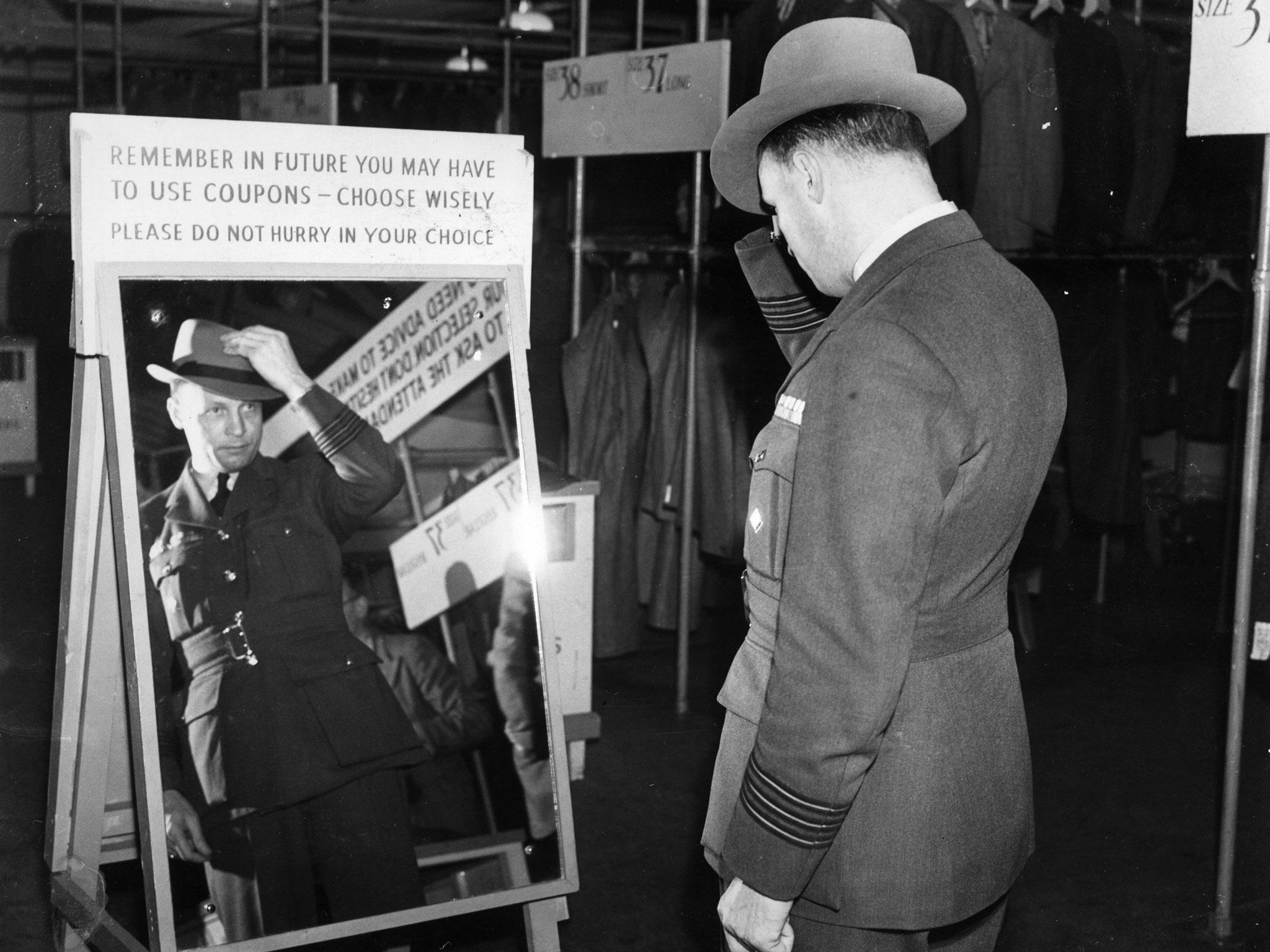

I don’t think I would have been too good at putting up with the torture though, if caught, betrayed by some faulty grasp of the imperfect subjunctive or an indelible English accent. The willingness – even eagerness – to torture your captives has always seemed to me like the hallmark of Nazism. Which is why I would like to recommend to President Trump – and anyone else who thinks torture “works” – not a fantasy or fiction, but the well-documented account of the wartime adventures of Wing Commander Forest “Tommy” Yeo-Thomas in The White Rabbit (one of his code names) by Bruce Marshall, published in 1952.

At the outbreak of war Tommy, whose French is impeccable, is working as the manager of a classy fashion house in Paris. He joins the RAF, carries out daring missions for the French Resistance, armed with a Sten gun and grenades, then is invited into No 10, briefed by Churchill himself, and parachuted at night into rural France in 1944. But alas he is betrayed and captured by the Gestapo at the Passy metro station. He is then beaten up, kicked half to death, handcuffed in stress positions, whipped while naked, and given the original “waterboarding” treatment, ie nearly drowned, in an actual bath, then revived, time and time again, and gets the dreaded electric shocks to the genitals to boot, but somehow, despite his all too natural terror, manages to hold back crucial information and save his comrades from being rounded up and tortured in turn.

“Schweinhund, salaud, terroriste!” as his tormentor calls him in bilingual rage. Tommy ends up in Buchenwald but amazingly escapes, survives the war, and goes back to his salon in Paris. Undefeated. I salute the extraordinary stoicism and fortitude and grit of real-life heroes like Yeo-Thomas (who, said Ian Fleming, was one of the inspirations for James Bond). Conversely, so far as I can make out, anyone who resorts to waterboarding and all the rest of it might as well wear Nazi insignia, no matter the cause. It’s just the Gestapo all over again. I’ll always be on the side of the guy in the bath.

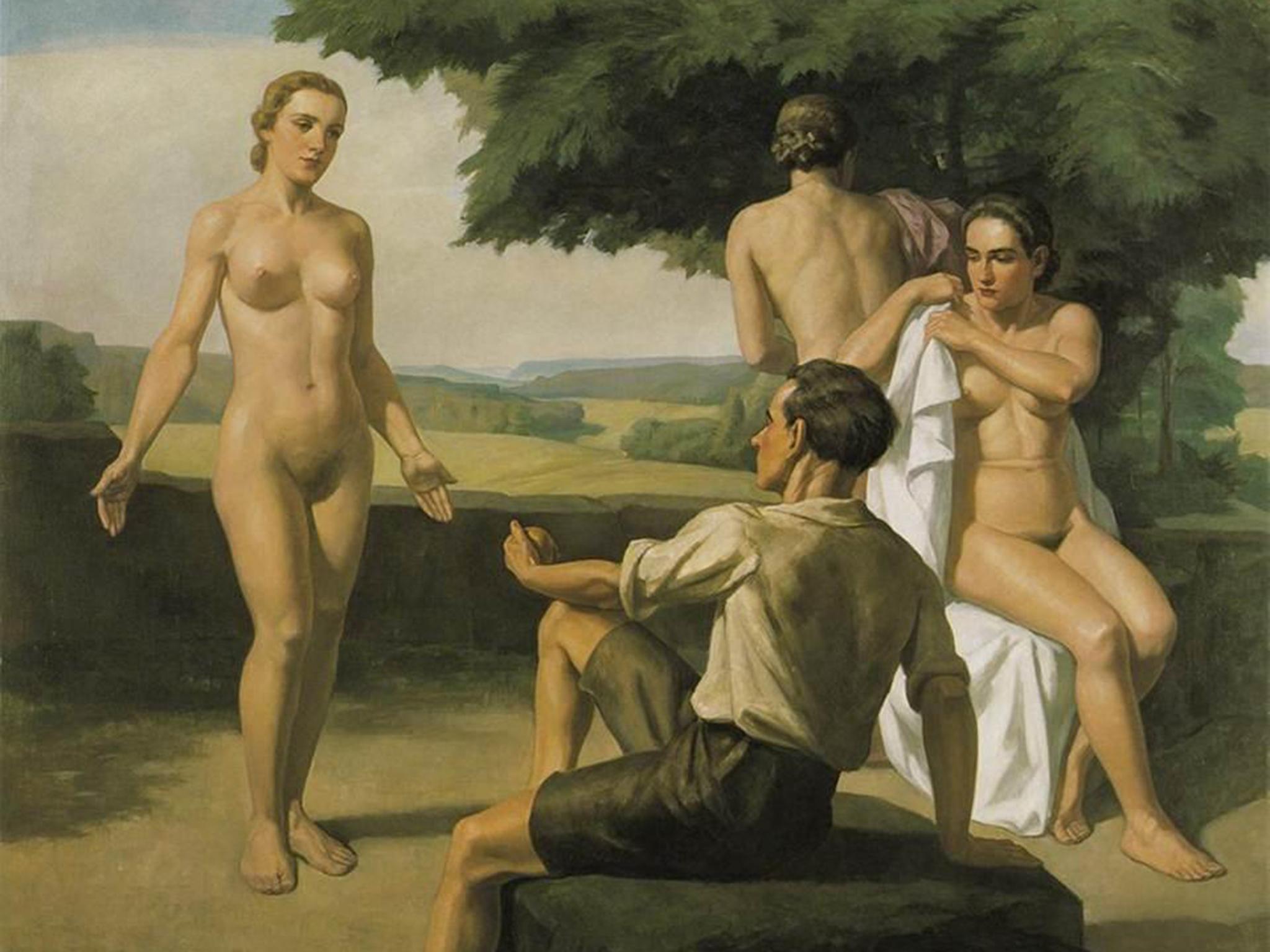

But there is another reason why, even if I had missed that last train out of Paris, I could never have surrendered to Nazism. No one can understand the appeal of Nazism who does not see that, beyond the sheer will-to-power and the sadism, there is a Nazi aesthetic. Which is summed up for me, seemingly at the opposite end of the cultural spectrum to torture, by Ivo Saliger’s painting, The Judgement of Paris, dating from 1939 (now in the German Historical Museum in Berlin). Hitler, the great artist, hated “ugly” – to his way of thinking, any deviation or impurity. In art exhibitions of the thirties and forties, Nazism projected and idealised and was evangelical about a certain narrowly defined physiology. Ivo Saliger was the kind of artist who wanted to curry favour with der Führer.

The original Judgement of Paris goes way back into Greek mythology. Paris, a handsome lad himself, was given the job (by Zeus) of selecting one of three naked goddesses as “the fairest” and awarding her the “golden apple” (he picks Aphrodite, who in return makes Helen of Troy fall in love with him, thus bringing about the destruction of Troy). In the Saliger painting, Paris is a Hitler youth lying on the grass wearing lederhosen, and is selecting an archetypal willowy blonde. Only blondes will do. The two dark-haired women are rejects and already putting their kit back on. In the middle distance is a wall. The point was that if you looked right, you were in, and if you didn’t quite measure up to the criteria, you were out.

If anything, the Greeks were more obsessed with archetypes of male beauty. I was once in a museum in Athens with a Greek guy, surrounded by statues of extremely statuesque male figures. They were all bearded and muscular and about to throw a discus or a spear or some such. Very manly. Huge. The Greek guy, who didn’t look in the least like any of the statues, drew my attention to the disproportionate smallness of the classic Greek statue’s manhood. It’s tiny. My Greek friend had a theory. “It’s like the sculptors want to give the rest of us a chance.”

Good theory. I think Greek philosophy was like that. It begins with Socrates, who was famously ugly. The whole of his philosophy is a critique of the Greek obsession with everything looking beautiful and perfect. Like a Grecian urn, in fact. Or a statue. Reality, he successfully argued, was not beautiful at all. When you inspect it closely, it turns out to be a bit of a mess. Nothing is perfect. Nobody is. Philosophy is a satire on our obsession with beauty. Pity he then made the fundamental mistake of assuming that beauty and perfection and truth would ultimately be attained in some sublime transcendent eternity (although I suspect that even he had doubts about it). Or as he irrefutably put it, “Only the Beautiful (to kalon) can be truly beautiful.”

Nazism is a dodgy translation of naked Greek archetypes with added torture. In Paris, in the 1940s, even before it was militarily defeated, it collided with the overwhelming force of existentialism. Embodied by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, neither of whom were ever subjected to the kind of treatment Tommy Yeo-Thomas had to take. But they hated the idea of Nazism, that you had to fit in. Sartre in particular liked to describe himself as “an ugly bastard” (and Simone de Beauvoir agreed with him). His autobiography Words is and inverted fairytale in which he is turned from a curly-haired “angel” into a “toad”. Whereas Camus was more of a Bogart of French philosophy and pronounced himself against existentialism (as all true existentialists must), being more of an Absurdist. But the point was that for both of them, it was OK to be ugly, you had the right to be an “outsider” (as per Camus’ novel, L’Étranger).

Sartre and Camus were the Lennon and McCartney of their day and were therefore doomed to split. But both Being and Nothingness (Sartre) and The Rebel (Camus) can stake a claim to being hymn, lament, protest, paradox, and poem of revolt. Against what? Just about everything, but especially Nazism and the totalitarian mentality according to which all critics are necessarily “the Enemy of the People”.

Emile Durkheim, the sociologist, had argued in the early years of the 20th century that the main cause of suicide was “anomie” – the state of “normlessness” in which the individual is floating free from the norms of society. Sartre and Camus, in their different ways, turn this around and say the real problem is normativeness, the enforcement of too many rules and criteria. Everyone is potentially or actually an anomic outsider, lonely even in a crowd. We shouldn’t have to look the same or talk the same or wear the same clothes or be “integrated”. We need to get over our tribalism. And there is no timeless perfection to look forward to either, this is all we’ve got, one life, only one shot. And above all, it’s ok to be a failure. Everybody fails. Everybody, ultimately, is a loser. Nazism, in contrast, was about nothing but winning.

Beyond The Man in the High Castle and SS-GB, my mind was concentrated by being on a panel of neo-existentialists speaking at the LSE Literary Festival event last night, “Existentialism is Easy”. And merci beaucoup by the way to the French embassy for the post-talk supper. The attitude, the mood, the metaphysics that is existentialism never died. But it occurs to me that, by the same token, maybe there ought to be a parallel, “Nazism is Easy” event too. The totalitarian temptation is always there. It’s a permanent potential in human experience. It hasn’t gone away. Anyone can flip. Whole nations can flip. Thus Camus at the very end of The Plague, his allegory of the Second World War: “He knew that… the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good, that it can lie dormant for decades in furniture and linen-chests, that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs, and bookshelves, and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

The world is haunted right now by the spectre of Nazism. When I went to Yale recently to have a chat with 80-something Harold Bloom (author of Shakespeare: Inventing the Human, and the forthcoming Shakespeare’s Personalities series), I said to him that the new zeitgeist in America was reminiscent of Paris back in 1968. “No, it isn’t,” he replied. Even though he is as much fun as Falstaff, he said, “It’s more like Berlin in 1934.”

Andy Martin is the author of “Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me” (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99). He teaches at Cambridge University. Follow him @andymartinink

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks