The Paris riots of May 1968: How the frustrations of youth brought France to the brink of revolution

Fifty years ago today the streets of Paris staged a battle between 6,000 student demonstrators and 1,500 gendarmes – within days it had snowballed into civil dispute that saw 10 million French workers go on general strike and brought the economy to a virtual halt. Andreas Whittam Smith recalls the events of ‘Mai 68’

The French always celebrate 1 May with a few riots. They did so this year with added piquancy because it was the 50th anniversary of the famous “Mai 68” when, in the Latin Quarter of Paris, the Left Bank, the whole month was devoted to riotous assembly led by students. In contemplating these events, I recall Wordsworth’s often quoted phrase: “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive” – unless, of course, you were struck by a cobblestone hurled by a student demonstrator or soaked and knocked off balance by a police water cannon.

Presumably those who were demonstrating in Paris last Tuesday have now resumed their normal lives. The point about May 1968, however, is that they didn’t go back to college or to work the next day, they carried on, some of them for the whole month. Why was that? After all, economic growth had been unusually strong, the country was calm, both politically and socially, inflation was weak, living standards had been rising and there was little unemployment.

Was it in a way a very 1960s thing? That question is prompted by a French historian of the period, Éric Alary, who observes that “May 68 is seen as a period when audacious moves seemed possible and during which society profoundly changed”. For that is an accurate description of the nature of the 1960s, whether in Western Europe or in North America.

At the same time, there was a big rise in the sheer number of young people as a result of an increase in the birth rate in the closing stages of the Second World War and for some years afterwards. Thus, in France, the under-20 cohort rose from 30.7 per cent of the population in 1954 to 33.8 per cent in 1968. At the same time in France (1967), the school leaving age was raised from 14 to 16.

This required a massive expansion of teaching staff and building. As a result, students often found themselves being taught by hastily trained teachers in hastily built class rooms. In France, as in Britain, this was followed by a big expansion of the university sector. There was inevitably something ramshackle about it all, and students noticed. Yet the command structures of educational establishments remained unchanged.

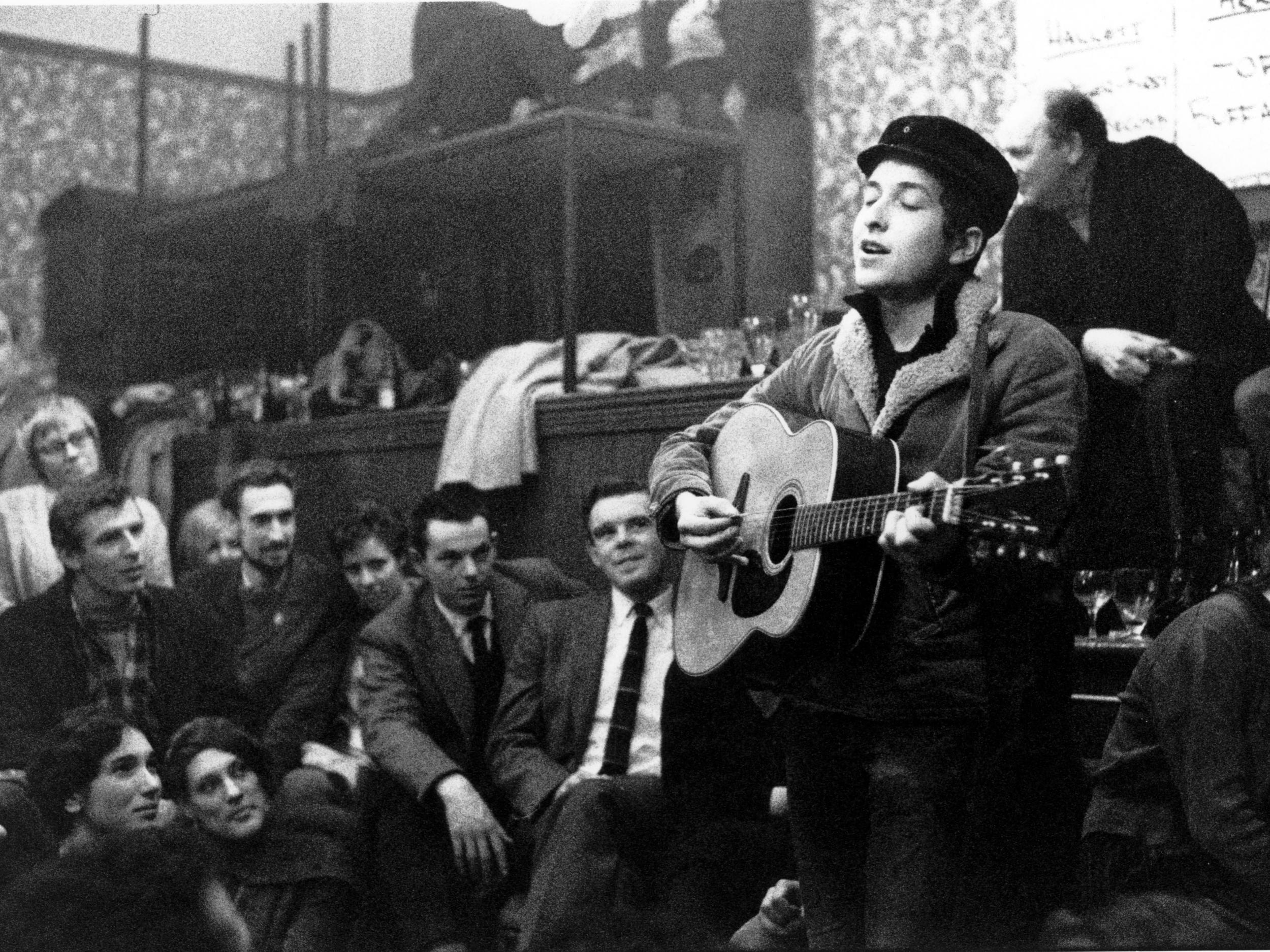

Nonetheless, universities are never just academic establishments full stop. For their campuses and their indoor and outdoor spaces lend themselves to meetings and debates and even to organising mini demonstrations. The intellectual gods of these 1960s students were Marx, Freud and Sartre, the French existentialist philosopher. In a famous passage, Sartre wrote that “God does not exist, and as a result man is forlorn, because neither within himself nor without does he find anything to cling to”. This struck home. For as Bob Dylan sang in 1965 – “How does it feel/How does it feel/To be on your own/With no direction home/Like a complete unknown/Like a rolling stone?”

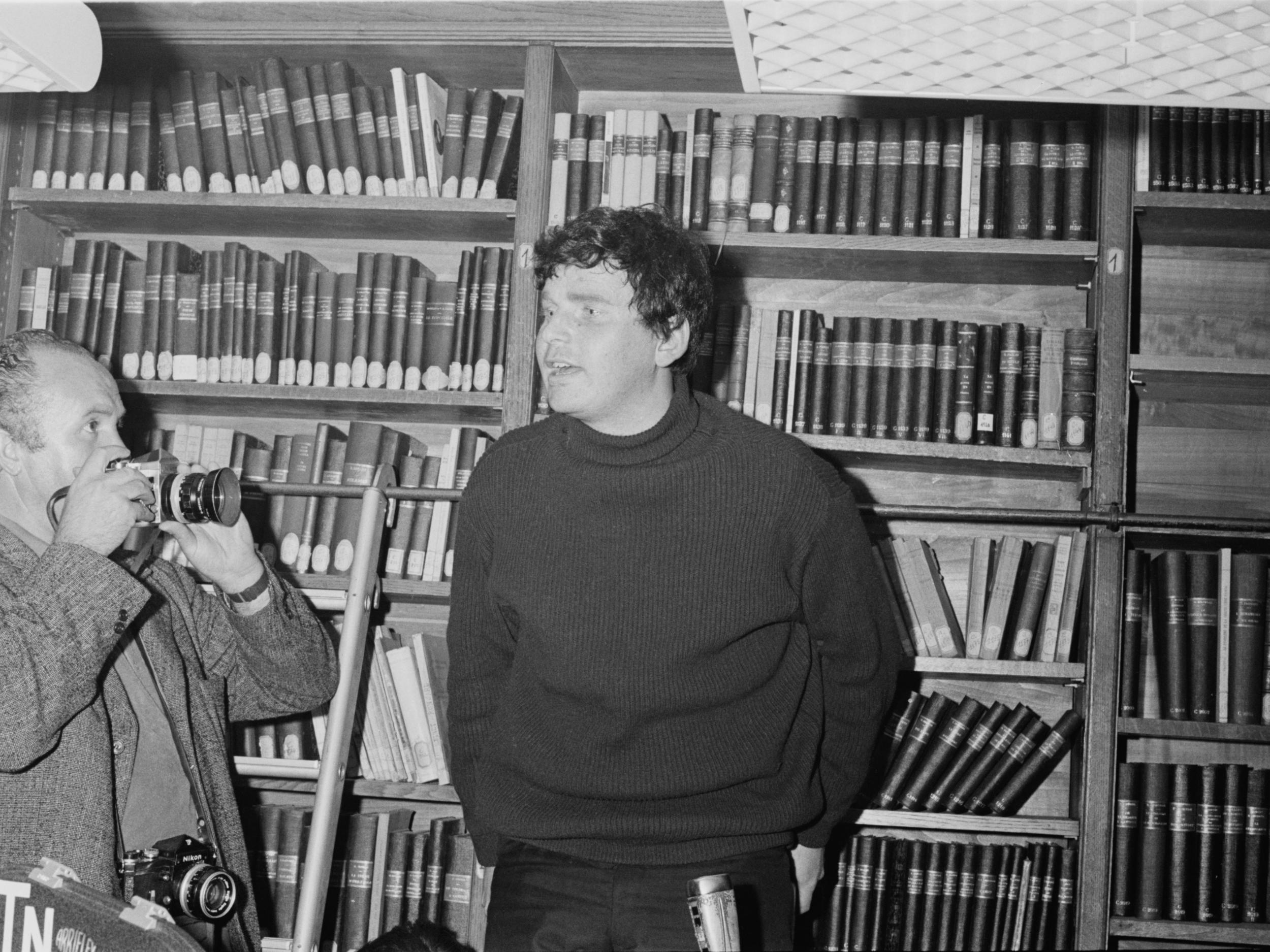

One had either to start things on one’s own without adult backing, or not at all. This was an unprecedented and intoxicating freedom. As the French student leader Dany Cohn-Bendit told the Paris demonstrators in May 1968: “There are no marshals and leaders today. Nobody is responsible for you. You are responsible for yourselves.”

In fact, as is the way of things, Mai 68 began not in central Paris, but in Nanterre, a suburb seven miles to the northwest, and not in May but on 22 March. The construction of the university of Nanterre campus in a bleak shanty town had begun in 1962. In the spring of 1968 it was still not finished. The building were exceedingly functional and contained some 12,000 students. They were particularly shocked to find themselves living and doing their studies in what was in effect a building site. They demanded, too, the right to circulate freely between the residences of males and female students, still forbidden in what one might call pre-1960s style. There was a lot of justified discontent.

Some 150 students, including far-left groups together with a small number of poets and musicians, occupied a building. The police surrounded it. After publication of the students’ wishes, they left the building without any trouble. But then they took their protest movement to the Sorbonne in the very middle of the Latin Quarter. That was how Mai 68 started.

In a drastic action, the authorities shut down the University of Nanterre on 2 May. The students who had decamped to the Sorbonne were bound to think that this was a hostile act, an outbreak of war between the university authorities and the student body. It had been natural to head to the Sorbonne, France’s premier university, which had the prestige of its ancient foundation 700 years earlier. This meant nothing to the police, of course, who invaded the Sorbonne the next day.

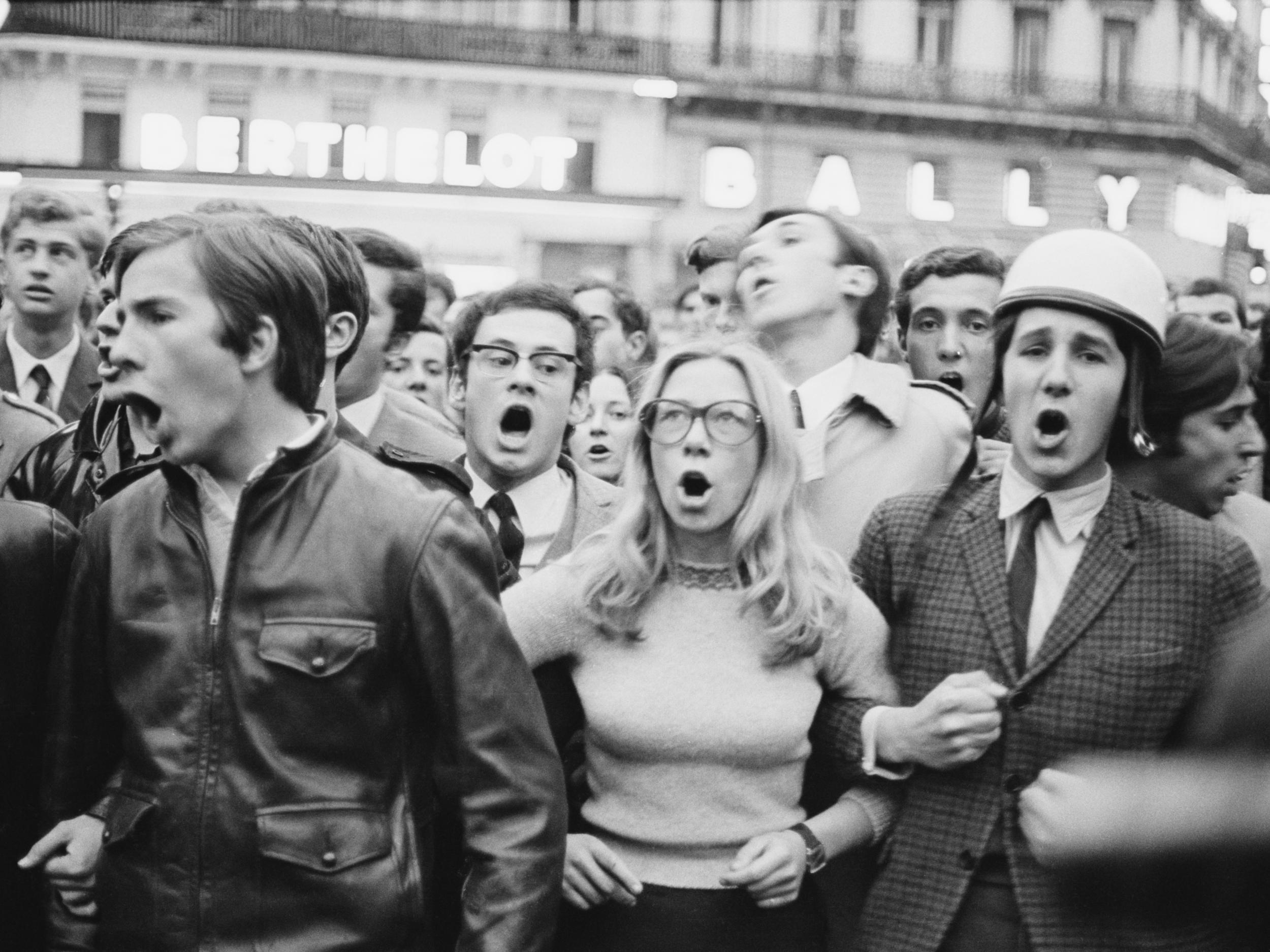

In response, on 6 May the national students’ union and the union of university teachers organised a protest march. It was one of the key events of the month. The head of the Paris police was obsessed by the need to protect the Sorbonne and its surroundings from a massive invasion by the students. He placed 1,500 officers in defence. But then came 6,000 protesters in waves. Overnight the confrontation was particularly violent. Thousands of cobblestones were ripped up and used as projectiles by the demonstrators. The police responded with teargas grenades. Dozens of gendarmes were taken to hospitals. Students were wrenched from the arms of the police by their colleagues.

The next day, students, teachers and increasing numbers of young workers gathered at the Arc de Triomphe to demand that all criminal charges against arrested students be dropped, that the police leave the university and that the authorities reopen Nanterre and the Sorbonne. But negotiations broke down. When the students returned to their campuses to find that the police were still in occupation, a near revolutionary fervour began to grip them.

The next big date was 10 May. The atmosphere became more and more tense. Left-wing students were seeking a confrontation and the force of law and order did nothing to avoid it. Senior politicians now began to fear that an insurrection was being planned that would soon set ablaze the whole country. When the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité, a special police unit specialising in riotous situations, blocked the demonstrators from crossing the river, the crowd again threw up barricades, which the police then attacked at 2.15 the next morning after negotiations once again floundered. The confrontation, which produced hundreds of arrests and injuries, lasted until dawn.

The events were broadcast on radio as they occurred, and the aftermath was shown on television the following day. This demonstration of heavy handed police brutality brought on a wave of sympathy for the strikers. Moreover, in a highly significant move, the major union federations called a one-day strike and demonstration for Monday, 13 May. The workers were going to march with the students.

They had their own grievances. There had been sporadic industrial trouble since the beginning of the year. More than half of them put in a 48-hour week. They feared that their standard of living had ceased to improve. Unemployment, albeit from a low base, was beginning to rise. As a result this was no longer a Paris event, for workers took to the streets throughout France. Their slogan was “Ten years! That’s enough!” referred to Charles de Gaulle’s long period as president.

The events the next day, 14 May, were as important. For workers began occupying factories, starting with a sit-down strike at the Sud Aviation plants near the city of Nantes. If students could occupy their universities, then workers could seize control of their factories. By 16 May, workers had occupied roughly 50 factories throughout France and 200,000 were on strike by 17 May. That figure snowballed to two million workers on strike the following day (18 May) and then ten million, or roughly two thirds of the French workforce on strike the following week (23 May).

The unions assumed that the workers simply wanted more pay. So, when they were able to negotiate substantial pay increases with employers’ associations, they thought their job was done. But workers had also demanded the ousting of the De Gaulle government and in some cases demanded to run their own factories.

The demonstrations and the strikes went on. Meanwhile on the morning of 29 May, De Gaulle suddenly boarded a helicopter and left the country. He went to the headquarters of the French military in Germany and called a meeting of Council of Ministers for 30 May back in Paris. On that same day, the unions led 400,000 to 500,000 protesters through Paris chanting “Adieu, De Gaulle”. The head of the Paris police carefully avoided the use of force.

Sensibly De Gaulle responded by dissolving the National Assembly and calling a new election for 23 June. He ordered the workers to return to work immediately, threatening to institute a state of emergency if they did not. The Communist Party agreed to the holding of the election. Immediately revolutionary feelings began to fade away. The police retook the Sorbonne on 16 June. And the Gaullists won the greatest victory in French parliamentary history.

The May days of 1968, it turned out, had been a convulsive moment, nothing more enduring than that. Nonetheless in Wordsworth’s words, “to be young was very heaven”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks