Northern Ireland is facing a suicide epidemic — but continues to be ignored in UK mental health funding

As the country struggles to escape the trauma of the Troubles, campaigners are desperately fighting for support from Westminster

“During secondary school, my sister unsuccessfully tried to take her own life and my friend’s brother died by suicide a couple of years later. I didn't think it hit me at the time, but it did.

“I had taken an overdose more than once too, but being diagnosed with heart failure in 2010 gave my life a new meaning – things began to get better when I came out of hospital. And then, at the end of August last year, my sister died by suicide.”

For Kieran Fitzpatrick, 37, suicide has plagued his whole life. He has been unable to escape his own mental struggles following his sister's death. “I tried to take my own life again, it completely threw me off guard.”

Kieran is from Downpatrick, a small picturesque Northern Irish town not far from Belfast, with just under 20,000 residents. The town is famous for being the final resting place of St Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, who according to legend, banished snakes from the island.

Today, the historic town is one of many in Northern Ireland facing a new and more deadly foe, a suicide epidemic. According to the Northern Ireland Statistic and Research Agency, 297 people took their own life in Ireland in 2016 alone.

What concerns mental health professionals most is the rapid increase in the annual number of suicides since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, despite the newly formed Assembly hopes to usher in a new era of prosperity and stability. In 1998, records show that 143 people took their own lives in Ireland, fewer than half of the number in 2016.

Another disconcerting statistic shows that more people in Northern Ireland have died by taking their own lives since the signing of the agreement than from violence during the Troubles.

Worryingly, suicide rates in Northern Ireland have also soared at a much faster rate than the rest of the UK. According to a report by the Samaritans, overall suicide rates in the UK have increased by 3.8 per cent since 2014, with a 2 per cent increase in England.

However, the number of deaths attributed to suicide in Northern Ireland has increased by 18.5 per cent during the same period, according to the findings. Northern Ireland's suicide trend is not representative of the whole country. Rates have actually decreased by 13.1 per cent in the Republic of Ireland, the lowest number there since 1993.

Male suicides are more common. In 2016, 221 took their lives, compared with 76 women, with men aged between 30-35 making up the largest group.

A further Samaritans report found that the number of men taking their own lives in Northern Ireland per 100,000 of the population had increased by 82 per cent from 1985 to 2015.

So why is Northern Ireland experiencing such an alarming and ever increasing suicide epidemic? Siobhan O’Neill is a professor of Mental Health Sciences at Ulster University and she has undertaken the largest study into mental health in Northern Ireland’s history.

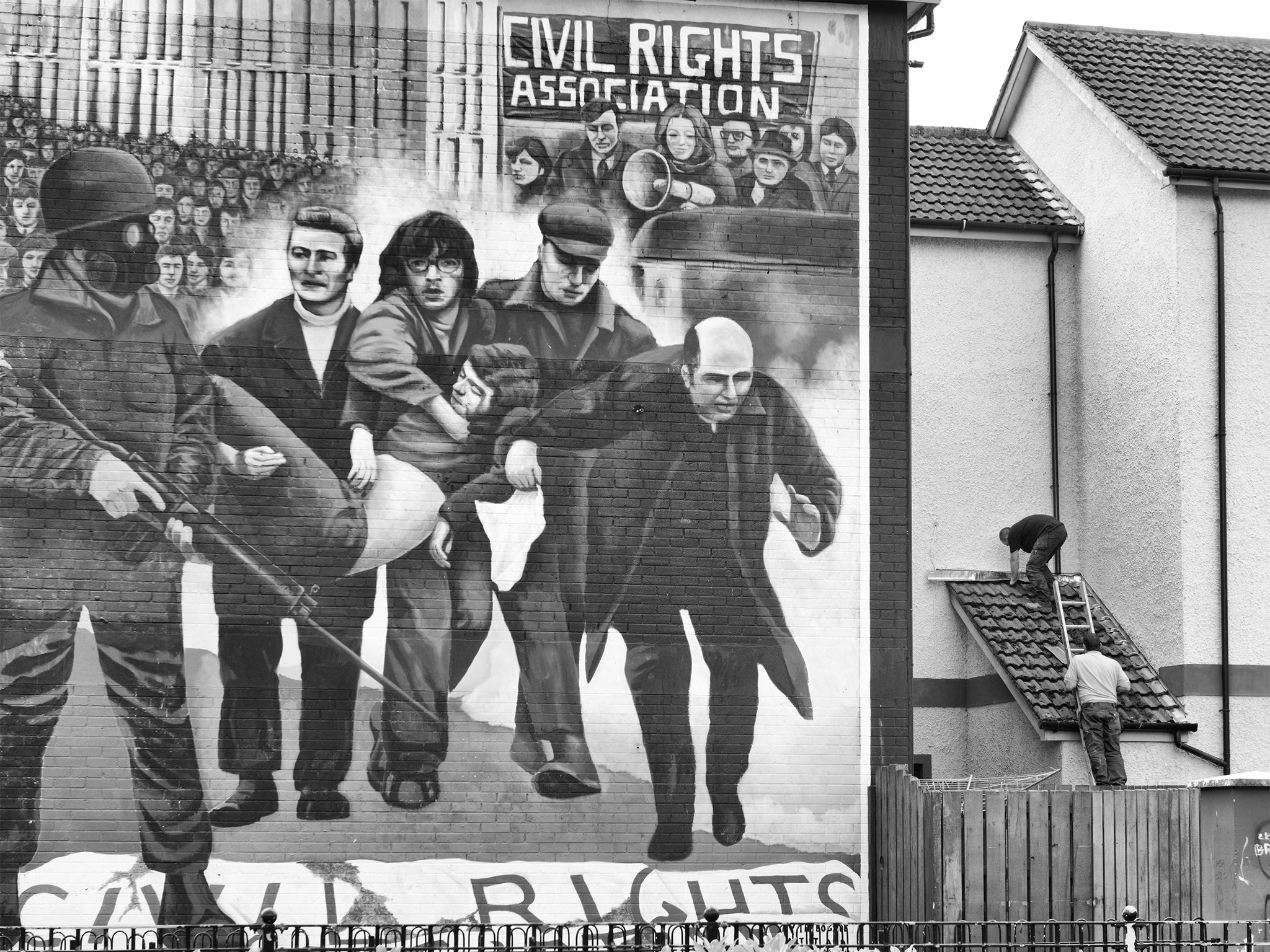

For Siobhan, the most significant factor is the legacy of the Troubles themselves and a failure to provide adequate treatment for those affected by the violence they witnessed. Her study into mental health revealed that almost 40 per cent of the Northern Irish population had witnessed a traumatic event associated with the Troubles, 18 per cent had seen someone dead or seriously injured.

She also studied the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), discovering that Northern Ireland had the highest rates out of the 30 countries examined, including South Africa and Lebanon.

“We see a clear link between seeing trauma and then someone inflicting trauma on themselves,” Siobhan explains.

“We have the issue now of living in a post-conflict society where people have to process what has been gained because of all the fighting.

“All the evidence we have shows that people in Northern Ireland are re-interpreting what they have seen or even done and it re-traumatises them."

A perceived lack of purpose following the signing of the Good Friday Agreement can also be attributed as a cause.

“When a society goes through conflict, it actually causes social cohesion because it brings people together to fight against something,” Siobhan adds.

“When that ends you see an increase in suicide rates because the connection that was there has gone. People have lost that power and a legacy of poverty and hopelessness returns.”

Despite this urgent need, Northern Ireland still receives significantly less funding to deal with suicide and mental health problems than the rest of the United Kingdom.

According to a study conducted by Northern Ireland's department of health in 2014, the country is reported to have a 25 per cent overall prevalence of mental health problems than England.

“We have a 20 per cent smaller budget than in England, with a 25 per cent greater need,” rebukes Michael McGimpsey, the former minister of the department.

Although funding for primary care has increased in Northern Ireland by 136.2 per cent since 2009, mental health services have experienced annual monetary reductions until 2016, a study by the Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care found.

Specialist mental health services are needed to deal with the unique concerns posed by the aftermath of the Troubles. David Babington is the chairman of Action Mental Health (AMH), a Northern Irish charity which aims to improve the quality of life for people with mental health needs.

AMH runs a variety of services, from teaching employers how to address mental ill-health in the workplace, to offering school children the chance to discuss any concerns they may have with therapists. The charity also offers free qualifications and counselling to help sufferers get back on their feet.

Babington is concerned about the lack of political representation for Northern Ireland, despite the specific challenges its society faces.

He recently led a delegation of charity representatives to Westminster where they met with MPs from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fein, as well as members of the House of Lords, in order to raise awareness of surging suicide rates.

A request to meet with the Secretary of State, Karen Bradley, remains unanswered. “Many of the problems come against the background that we don’t have a local assembly that would normally look after us and our issues and control the health budget here,” Babington told the Independent.

“We haven’t had a proper devolved administration here since the end of 2016; it has been over a year now and there is no prospect for this to change.

"After telling politicians that we need help, we were promised more funding for mental health which still hasn’t been given."

Alongside the legacy of the Troubles and a critical lack of mental health funding, there is an apparent depletion of political will to address the high rates of deprivation and unemployment, particularly in areas of North and East Belfast where spiralling alcohol and drug dependency levels are causing suicide figures to rise.

Northern Irish society is also considered to be one of the most conservative in Western Europe, with the church retaining a strong influence over societal norms.

“Particular religious denominations mean that whole waves of our population feel much more closeted,” Siobhan states.

“It’s simply a toxic mix of factors,” echoes Babington. Many local charities and voluntary groups are working hard to bridge the funding and services gap.

Peter Thompson is a centre co-ordinator at the Ballysillan Youth for Christ (BYFC) organisation, known as the ‘Blue Houses'. They work in an area of North Belfast with some of the highest rates of poverty in the whole of Northern Ireland.

Around 60 per cent of the population of Ballysillan also has no or a low-level of qualifications. Alongside running workshops and drop-in sessions, BYFC's volunteers also work tirelessly in local schools, alleviating pressing mental health issues and run inter-generational workshops to assist parents struggling to raise their children while living with the legacy of the Troubles.

Their volunteers work in local schools to alleviate pressing mental health issues and run inter-generational workshops to assist parents struggling to raise their children while living with the legacy of the Troubles.

However, the future of the Blue Houses hangs in the balance.

“We have lost some significant funding recently and have found it difficult to access other funding streams." Peter Thompson confides.

“If we don’t have a major turnaround in the next few months our team will be reduced to two employees, which will be a disaster for the community and young people.”

Northern Ireland is full of people like Peter who possess a genuine will to change the lives of those suffering from mental health problems.

However, organisations suffer from severe funding constraints and a lack of country specific services.

Envious eyes are cast across the Irish Sea to England, where in April Jeremy Hunt introduced £25 million of additional funding to tackle suicide rates in England, with nothing announced for Northern Ireland.

In Downpatrick, Kieran attributes AMH’s group therapy sessions and skills workshops to saving his life.

He obtained his Level 2 Customer Service qualification through the group, obtained a work placement and was then given a permanent position.

“I’m in a good place now,” he says, smiling.

“You can still have your days where you question yourself, but I can put my past behind me and go on. I don’t think that I could have done this without the help of AMH and the stress management and personal development courses that they offered.”

Along with several friends, Kieran has now opened his own mental health charity called All Lives Are Precious (ALPS).

It was a proud moment for Kieran when the organisation recently held its first Downpatrick’s Got Talent competition, which aims to show local youth that they are talented and that their future is indeed a bright one.

“The money that we should have been getting for mental health just hasn’t been released,” Kieran asserts.

“All my life I was a nationalist but I don’t care who is in power now. I just want somebody to be there to offer the funds that are needed."

I catch up with Siobhan O’Neill for one last time, she is celebrating her daughter’s first birthday. Laughing as her daughter attempts to snatch the phone off her while we are in mid conversation, she reveals her true motivations for working in the sector.

O’Neill suffered a breakdown herself after a crisis in her personal life and was struck by how many people she knew in Northern Ireland who were being crippled by mental health issues. “I just didn’t want the next generation and my child to have to go through what me and many of my friends have been through,” she says with determination.

“I want it to be so much better for them, you know?”

If you have been affected by any of the issues discussed in this article you can contact the Samaritans on (0)20 8394 8300.

The organisation also runs local offices in Northern Ireland on +44 (0)28 9066 4422, in Scotland on +44 (0)131 556 7058, in Wales on +44 (0)29 2022 2008, in Ireland on +353 1 6710071.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks